The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego: Far lands and forgotten times

Out last month, The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego is a book featuring the amazing photos of Martin Gusinde, a German missionary who travelled to South America, to the islands of Tierra del Fuego to observe the native cultural and religious life of the natives.

Interview by Yetkin Nural

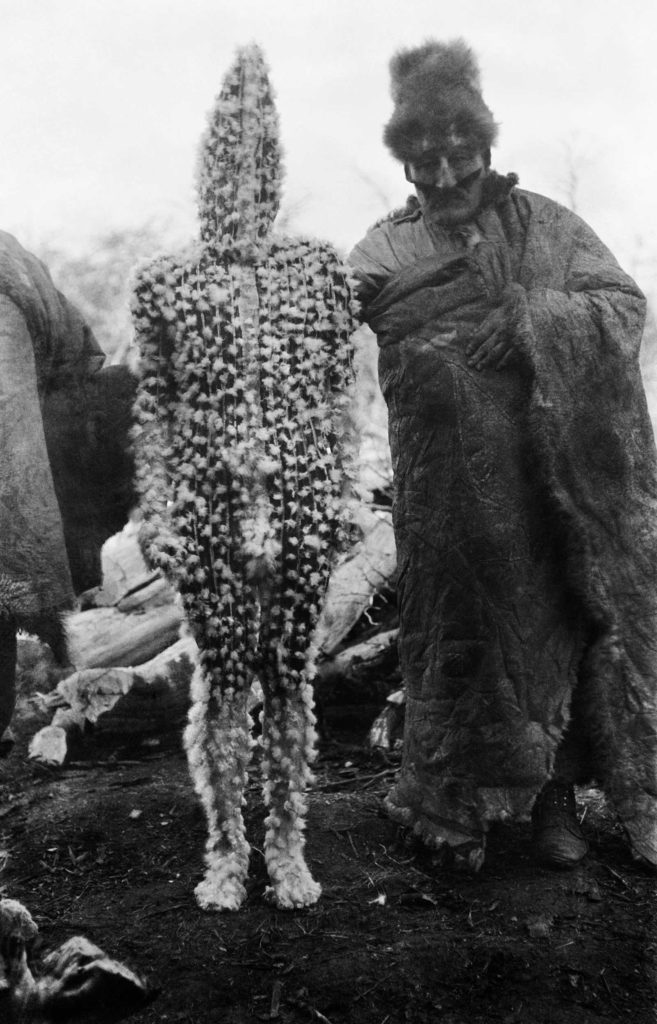

The religious costumes and body paints as well as the rituals of the Selk’nam, Yamana and Kawésqar people, the residents of Tierra del Fuego, are so mind blowing and creative that Guisinde’s black and white photos give the other-wordly feel of the 70’s sci-fi book covers. We talked with the co-editors of the book, Xavier Barral and Christine Barthe, who gave us this visual treasure of a book after a thorough archive research.

How were you introduced to the works of Martin Gusinde? What sparked the idea of creating a book dedicated to his times and work with the tribes of Tierra del Fuego?

Xavier Barral: I discovered these photographs as I was sailing along the Patagonian coast in 1987 in a museum on Navarino Island dedicated to the societies that lived there. And I met Anne Chapman who was carrying out her research. I only found out almost 30 years later who the photographer behind these astonishing images was, thanks to Christine Barthe and where his photographs are archived by the priests of the Anthropos Institut in Sankt Augustin, Germany.

Christine Barthe: As part of the research I conducted for an exhibition on Patagonia at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, I was able to locate the archive of these photographs that I had discovered a few years earlier. After several visits to the Anthropos Institut, I exhibited some of these photographs in the exhibition that opened in 2012. I met Xavier two weeks before the opening of the exhibition, we talked about theses pictures, and then Xavier decided to launch the book project.

When I discovered the 1,200 negatives and prints in the archive, I decided to make a book as there had never been one dedicated to Martin Gusinde’s photographs which celebrate the spirit and memory of these peoples. With the kind permission of Dr. Joachim Piepke, director of the Anthropos Institut, we were able to digitize the original negatives conveying an optimal and unprecedented printing quality for these images.

As the introduction text of the book says, Martin Gusinde was one of the rare Westerners initiated into the sacred rites of the tribes that he was living with. What do you think allowed him this access? Was it his own interest and respect for these people or the welcoming cultures of these particular tribes?

XB: Martin Gusinde arrived in Chile in 1912, six years prior to his first trip to Tierra del Fuego. He was sent as a teacher to Santiago de Chile. During that time, he took an interest in the culture of Chilean societies and started working for the recently opened Museum of Ethnology and Anthropology in Santiago. Through this initial experience, he decided to complete his research by going on-site. His first excursion in Tierra del Fuego was in 1918-1919.

CB: Martin Gusinde was deeply immersed within these societies through four long journeys, to the point of speaking their language, which enabled him to get access to their daily life and sacred rites and thus developed a trusting relationship. He was also very respectful and didn’t convey an artificial and romantic image of these peoples. Him being a missionary probably gave him a particular sensitivity to religious rites.

XB: From his first journey, Gusinde understands that these societies are endangered by their contact with the Westerners through mostly diseases they weren’t immunized against or attacks by some miner and breeder settlers. And he decides to conduct an in-depth study of the Selk’nam, Yamana and Kawésqar by photographing them and making field notes.

The Shoort spirits Télil, representing the sky of rain (northern sky), and Shénu, representing the sky of wind (western sky). Each mask, known as an asl, was made of guacano leather stuffed with dried leaves and grasses.

While all tribes around the world have their own cultural / religious rites which include visual and aesthetics components, the tribes that Martin Gusinde studied, Selk’nam, Yamana and Kawésqar people, have extraordinary ways to create the most spectacular forms of expressions of their culture and beliefs. What do you think makes these tribes special or different?

CB: I believe it is more the little knowledge we have on these peoples that makes this photographic testimonial so special. Their culture being essentially oral, we are all the more surprised and fascinated by these photographs presenting bodies in their most extraordinary expressions with ritual paint. These portraits enable us to catch a glimpse of the legendary and rich diversity of societies that had until then barely been considered worthy of attention.

XB: Also, what is very particular of these societies is that they lived at the most southern tip of the world, in extreme climatic conditions. In this isolation, they had developed a singular oral culture based on a mythology passed on over thousands of years. The presence of human beings in Tierra del Fuego goes back to approximately 10,000 years as researcher Dominique Legoupil explains in her text.

K’termen, the spirit Xalpen’s baby, is presented to the women by the sahaman Tenenesk. Entirely daubed in red ochre, his body is covered with fluffy goose down.

The captions in the book give a very detailed explanation of what is going on in the pictures. Do you not think that the text is insufficient to compliment the incredible photography? Does it not distract from the information in the images?

CB: The captions in the book convey the scarce knowledge we have on these societies and their rites, providing a few keys for interpretation on these images but it doesn’t stop the imagination, quite the opposite.

XB: Each of these photographs can be presented without a caption but as it is originally conceived as a testimonial on these peoples and not as a work of art, it felt important to present the factual information we have on these photographs by cross-referencing Gusinde’s notes and a current state of research on these cultures.

Due to the technology at the time, all of the images are in black & white. Yet from the captions we learn about the colours of the costumes, the body paint, the textures or materials used. What do you think about the effect of seeing a black and white photograph that is both in description and in feeling so colourful?

CB: This reminds us that it is a photographic testimonial not the real life, including technical constraints and the photographer’s approach in what he decides to present. Photography being a reconstruction of reality.

XB: Martin Gusinde actually described these colours in his notes on the back of the print and in his diaries so it was important to keep these references.

Gusinde used a portable dark room to print the films he shot. Which also means that he was able to show the photos to the people he captured. Is there any information on the reaction from the people?

CB: It is most likely that Martin Gusinde has shown these images to his subjects in order to explain what he was doing but there. It is only a hypothesis at this stage but we will soon know more as his diary is currently being translated.

XB: Yes, it does seem like he has developed his photographs on site but we don’t know anything yet about the people’s reactions.

How did you access and select the images in the book? Is there any plan for an exhibition, maybe one that tours around the world?

CB: We have made several trips to the Anthropos Institut who kindly let us scan the negatives. And the edits were made in different stages as we were working on the sequencing of the book for a final selection of 230 photographs.

XB: In our editing, our intention was to convey the most complete testimonial on these three societies. From the images in the book, we have also worked on a different selection for the exhibition we are co-curating as well. The exhibition will be presented at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles this summer. It includes 150 prints made with a carbon pigment ink by the French lab La chambre noire. The exhibition will then tour in several venues throughout Europe and South America.

Book credit :

The lost tribes of Tierra del Fuego (2015)

French & Spanish versions: Éditions Xavier Barral, available on the website: exb.fr

English version: Thames & Hudson