George Martin: the fifth Beatle

“Once [Martin and the Beatles] got beyond the bubblegum stage, the early recordings, and they wanted to do something more adventurous, they were saying, ‘What can you give us?'” Martin told The Associated Press in 2002. “And I said, ‘I can give you anything you like.'”

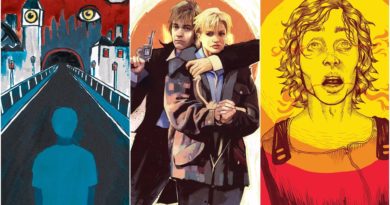

Text by Alex Mazonowicz – Illustration: Ethem Onur Bilgiç

Phil Spector was aggressive and determined, asserting full control of his records to the point of wielding a loaded shot gun in the studio. Brian Wilson was obsessive and neurotic, eventually shelving his most ambitious project and retiring to bed for 20 years due to drug-induced psychosis. Berry Gordy was a shrewd and flamboyant business man, turning his love of music into a hit factory and creating one the greatest musical empires ever. George Martin was a mild, straight man who doesn’t really seem to fit into the 60s narrative at all.

He came from the most unremarkable of British families, showing an aptitude for music at an early age. His work life started out with a stint as a filing clark, before he joined the air force, and then studying music. His love of Rachmaninov led him to a job for the BBC’s classical music department, and then EMI. At EMI he worked on the Parlophone label, which at the time of his joining had been left by the wayside and only used for less significant of EMI’s acts. He started making comedy recordings, working with Peter Sellers and the Goon shows.

Martin’s perchance for experimentation started early. He worked with electronic musicians from BBC Radiophonics on the 1962 dance single “Waltz in Orbit”, a record featuring sped up piano and synthesizers. His comedy records required sound effects, and clever editing. He once had to edit out the letter “K” in a goons skit about The River Kwai in order to avoid legal problems with the makers of the film of the same name. On an early Rolf Harris recording he close miked a wobble board, creating Harris’s signature sound. At a time when commercial record recording was little more than placing a microphone in a room and getting a good performance, Martin was commitment to breaking the rules to get the best sounds.

His ambition for the Paraphone label went beyond novelty tracks and comedians though. He wanted rock’n’roll, a style he loved but at his own admittance, didn’t really understand.

The story of how he came to work with the Beatles is one of the best know in pop music history, four lads from Liverpool who had been turned down by numerous labels came to London. On completing a test recording Martin, the caring gentle man he was, turned to them and said “If there’s anything you don’t like, we can change it”.

“Well” replied George Harrison, “I don’t like your tie for a start.”

The more romantic way of looking at this meeting would be to suggest that that was the moment Martin was sold on The Beatles. Their cheeky humor and charm, but Martin was a professional and must have heard something at that session that sold him. The Beatles were tight and energetic, they played louder and faster that the UK hit acts at the time. They had a varied repertoire, and an ear for quality, taking cues from the harsher sounds coming from the Atlantic. It was clear that Martin could learn as much from then as they could from him.

The defining moment in the Beatles-Martin relationship would be after their first single “Love Me Do” failed to make the impact that they had hoped. He was unhappy with the single, plodding and without direction, and looked outside a new song for the group to record, a common practice at the time. In fact the record he found “How Do You Do” became a hit later on for Gerry and the Pacemakers, another Martin recording artist, but the Beatles were unhappy with it. They insisted that they record one of their own songs, so Martin sent them back to Liverpool, suggesting that the Lennon-penned “Please Please Me” could be sped up. The resulting record, now a driving rock’n’roll tune, was a success. “Gentleman, you have just recorded your first number one record” was Martin’s comment. An idiom now ingrained in recording history.

In the early days of the the Beatles career George Martin treated his new signings with the best of care. On his own he renegotiated the band’s contract, doubling their royalties. He found them better publishers and advised on promotion. The resulting partnership was a commercial juggernaut. The Beatles success became a phenomenon, and Martin went on to sign a whole roster of Liverpool-based acts, including Gerry and the Pacemakers and Cilla Black.

But beyond the Beatle-mania and the money making machine, the group and Martin were changing the way records would be made for ever. Every visit to the studio would bring a new idea. The microphones got closer to the drums, and when they wanted even harder sounds, Martin has a small speaker cone modified to become a bass drum microphone. He played with the tempo of the records to get a tighter, more exciting feel.

By the time they got to Rubber Soul and Revolver, the Beatles were unrestrained in their requests. On the recording Tomorrow Never Knows, Lennon asked to sound like some Tibetan monks chanting from the top of a mountain. Martin complied by running his vocals through a rotating Leslie speaker. McCartney had been playing with tape loops, and together the five of them created a sound collage recorded on top of the track.

Elsewhere on the Revolver album Martin’s classical chops would be put to the test on the track “Eleanor Rigby”. The song required strings, but McCartney wanted something different from the standard lush orchestrations of the time, expressing his love for the distinctive string stabs on Bernard Herrmann soundtrack for “Pyscho”. Martin’s score for the track was astounding, and Eleanor Rigby became a seminal chamber pop track.

The partnership between Martin and The Beatles has been written about in great detail. Seldom has a partnership resulted in such innovation, and the relationship was unique for the time. George Martin forever remained a father figure, distanced himself from the drug use, spiritual journeys and infighting, always turning up in a shirt and tie and always business like. But he also had the insight, and an uncommon empathy, to be able to get the best out of the band. He understood the potential of the individuals, and worked as a servant or guide, rather than a director or enforcer. He would translate Lennon’s bizarre requests into solid ideas, encouraged McCartney’s inquisitive nature beyond rock’n’roll, nurtured Harrison’s skills as a musician and pushed Starr to come up with some of rock’s most enduring drum parts. And in return the band challenged Martin’s skills to a point far beyond any other artists in the producer’s career.

Away from the Beatles George Martin always approached recording with flair and a desire to innovate. He worked with America, Ultravox and UFO, to name but three, composed numerous film scores and released a handful of stunning records, including the synth-soaked Theme One. He became one of the first producers to work independently, a time when there were contracted to studios, which enabled him to share in record royalties. His contribution to the role as the record producer as an artist is immeasurable.

Much has been debated about the role Martin played in the Beatles success. Clearly they were a fine band with incredible ideas, and without Martin they would have been successful. But then as individuals they could have been successful. Lennon and McCartney could have led bands on their own, both formidable song writers and front men. Harrison was a perfect rock’n’roll guitarist at a time when such talent was in demand. Starr was already an in-demand drummer before joining the Beatles (he was the only one of the group making real money from performing before they were signed). But the serendipity that bought the four together to create the blueprint for the self-contained guitar band, also took them to Martin, who enabled them to reach their full potential. And what a potential. What a catalogue of songs. What an incredible collection of recordings, each one treated with care and enthusiasm. From the chiming strings of Ticket to Ride to the orchestral orgasm of A Day In The Life, each score written, each instrument recorded, each effect added and each mix conducted created its own unique magic.

The Beatles split from Martin for their Let It Be sessions. Although the song writing was a tight as ever, the sessions initially failed to materialise in anything they were happy with. Almost broken from the project, the band went back to their trusted mentor to make one last album, he agreed on the condition “we do it exactly as we used to”. The result was as magnificent and inventive as anything the band had ever done before. The album was affectionately titled “Abbey Road” the name of the studios where Martin and Beatles changed the way pop music would be made for ever.

George Martin. Producer. 1926-2016