Punk İbrahim Müterrefika

“It is not important what you get and from where, but how you put it all together.”

A few years ago, as I was walking down the back alleys, off Istiklal Street, I came across a fanzine exhibition at a fancy art gallery. Without a second thought, I walked in. The first thing I thought was, “No one would allow fanzines to be exhibited in a corporate gallery like this – this is probably an exhibition of photocopied literature or art publications from recent years…” To my surprise, that was not the case. Inside, on the shelves, was almost every Turkish underground-culture zine dating between 1990-2000. I assume that the gallery either collaborated with someone with a serious collection or went into various archives to put on this show. I stayed several hours, reading fanzines – especially the ones I do not have. I wished that the curator had put a photocopy machine at a corner of the gallery, so I could duplicate some of the issues missing from my own collection. I also thought that if someone had put on this exhibition 15 years ago, it would have received some negative reactions. I remember a similar show in Kadıköy – in its opening week, someone came, collected all the exhibited fanzines and replaced them with their own. I cherish this memory as the most beautiful protest that I have ever witnessed.

Words and Archive Erinç Güzel

*Ibrahim Müterrefika was an important Hungarian-born Ottoman figure who was the first Muslim to run a printing press.

FANZINES HAVE A TRANSFORMATIVE POWER. JUST LOOKING AT A FANZINE THAT SPEAKS TO THEM IS A WAY FOR A PERSON TO EXPRESS THEMSELVES. AT LEAST FOR ME, THAT WAS THE SITUATION. WHEN I STARTED TO PUBLISH MY OWN FANZINE IN THE EARLY 2000S, ISTANBUL ALREADY HAD A RICH HERITAGE OF INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING FROM THE 1990S.

On my way out, I asked a gallery manager if anyone had left their own fanzines after coming to the exhibition. He didn’t understand me, so I repeated my question: “Did anyone bring their fanzines after coming to see the exhibition?” He said: “Yes, of course, our artists will bring new fanzines very soon.” Some counter culture, huh? I turned around and left.

This answer bothered me. Let’s assume that the gallery manager simply didn’t know what was on the shelves and forget about him – but what if the people who saw the exhibition and were introduced to the concept of fanzines for the first time thought that these publications had not been created, as they were, by everyday people with something to say, but were a publication style reserved for people with a background in the arts? It is not impossible – after all, no one does it themselves and no one learns at home any more. Still, I managed to snap out of it, thinking: “Even if they do get that idea, they can just read a page of Disguast, and that will change their minds.”

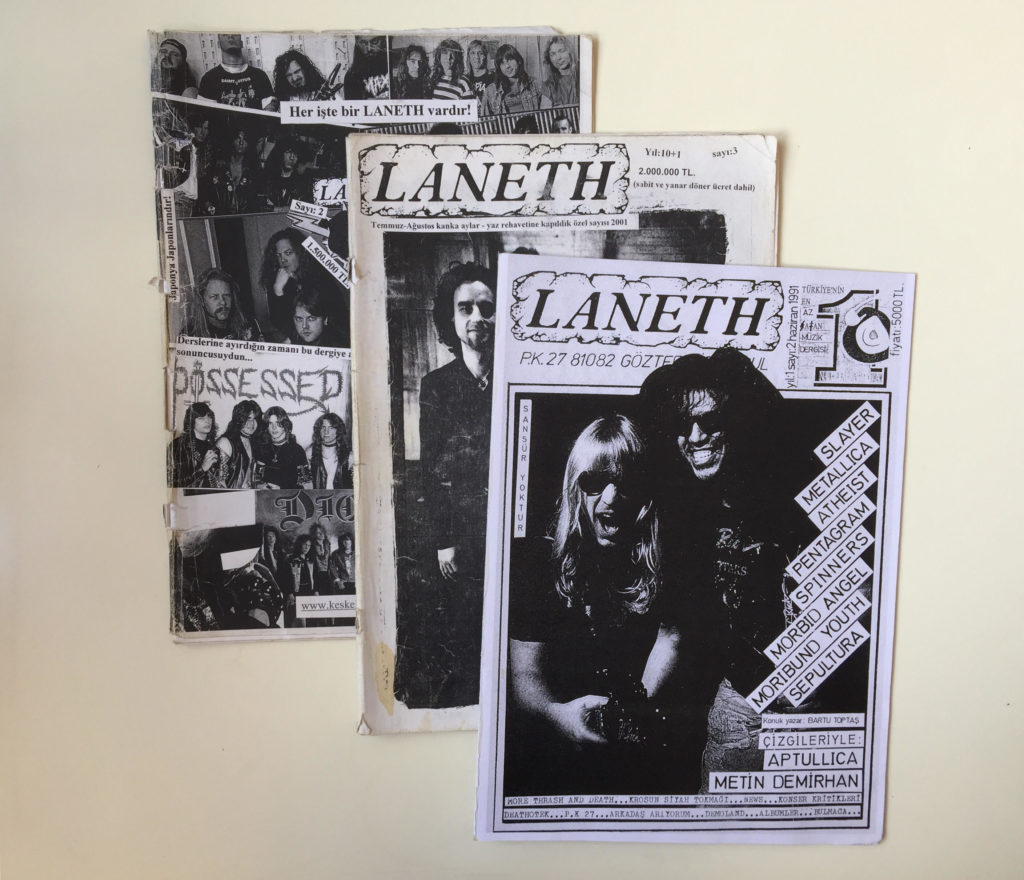

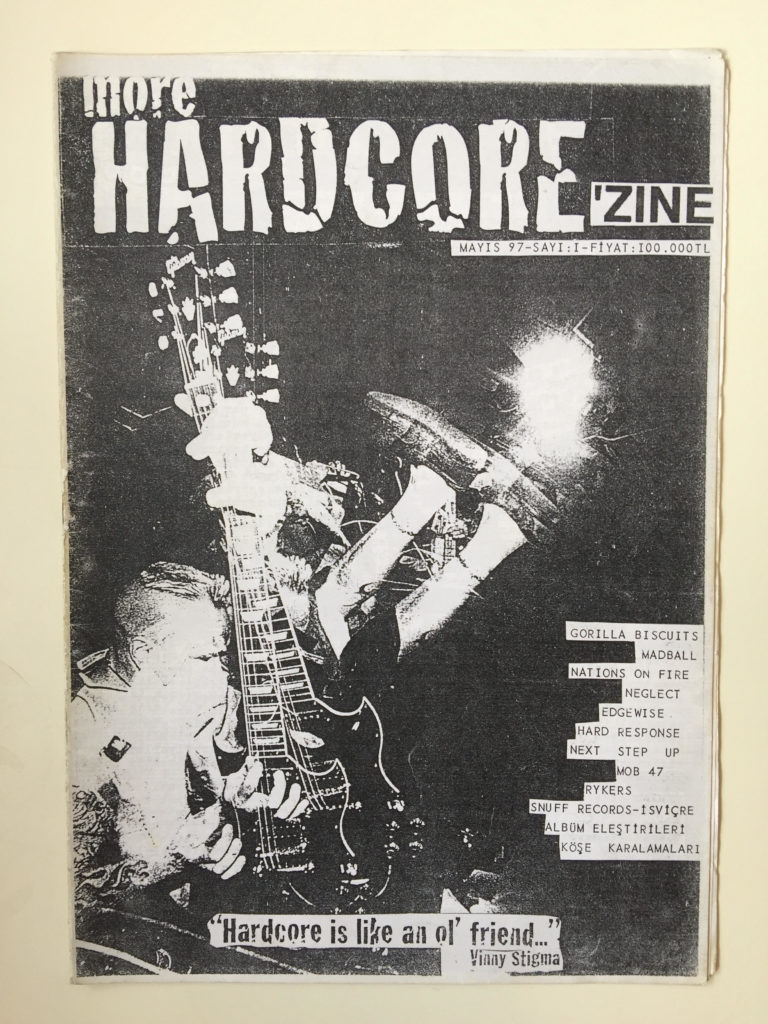

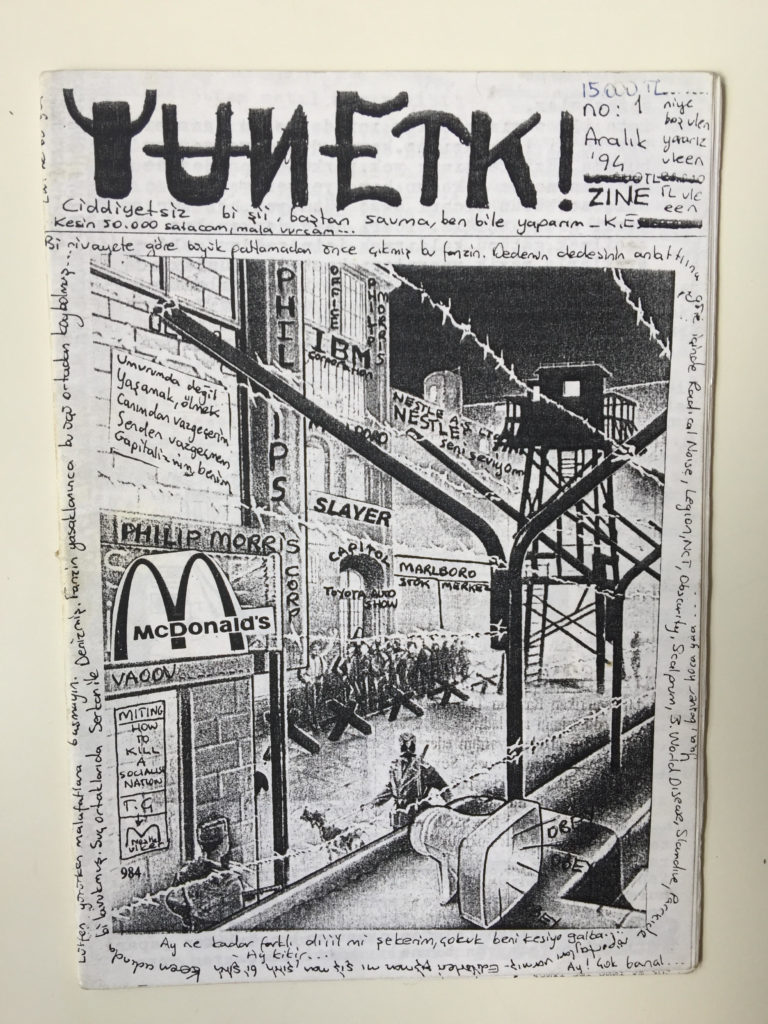

Fanzines have a transformative power. Just looking at a fanzine that speaks to them is a way for a person to express themselves. At least for me, that was the situation. When I started to publish my own fanzine in the early 2000s, Istanbul already had a rich heritage of independent publishing from the 1990s. If the London-based 1970s punk zine Sniffin’ Glue was an international milestone (and every city has its own milestones), Istanbul’s were Mondo Thrasho and Laneth. These DIY publications took different aesthetic routes and were claimed by different scenes, but both started with the same idea. Later, many others followed: Gorgor, More Hardcore, Yanetki, Yeraltı, Disguast, %30, Goblin, Probabilite, Gorefanzine, Mafia Joyful Company…

Even though, for various reasons, Turkey lagged behind the rest of the world in the 1990s, the local hardcore, punk, metal and extreme music scenes were stronger in the metropolitan areas of the west coast. There were more public spaces that allowed people to come together, more platforms, more groups. In the midst of all this, there were genre-specific music magazines, underground publications and fanzines. Even though music and popular culture were changing, the second half of the 1990s remained largely the same. Laneth had stopped being published but it was replaced with Non Serviam, which had nationwide distribution. This fanzine mostly focused on genres like black and doom metal, but because of its wide selection of writers, it was possible to read about Mayhem, then turn the page and read a piece on hardcore punk, then turn another and come across a feature on industrial music. Even if you were not plugged into the social circuits of these subcultures, even if you were just out of high school and living in a remote Anatolian town, it was possible to walk in a grocery store and get Non Serviam. This was how reports of what was happening in the big metropolitan areas reached past the city limits.

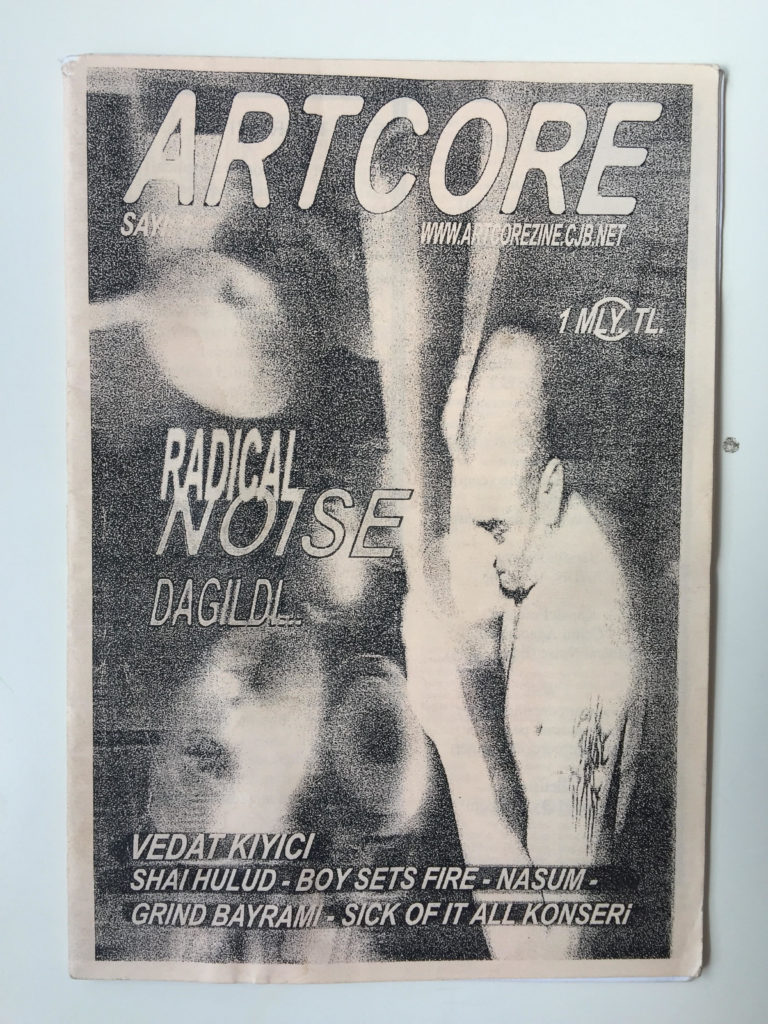

As Turkey entered the new millennium, only a few of the fanzines and distributors that were active during the previous decade remained. Soon after, they were gone too. Only in Istanbul did the scenes that fuelled these publications still exist, and they were confined within tight geographic borders. Back then, the “Kadıköy sound” meant hardcore punk; Bakırköy was the proud headquarters of death metal; Taksim, meanwhile, was writing its own mythology of punk. In a short amount of time, a new wave of bands started to appear and make a name for themselves. There were also new distributors: Extreme Response, AMA Tapes, Ats2 Distro, Attack to Society… In parallel, there was also a new wave of fanzines: Asperger, Artcore, Sonic Spleandaur from Ankara, Aparkat, Taygır Aparkat, Kuzeyden Aparkat,Cinnet and Darbeli Matkap from Bursa…

Let us digress for just a second. Say one day you decided, “I want to write about what is going on,” and made your way to a printing house. If you didn’t have a fat wallet, the first obstacle between you and your own media empire was finances, because printing houses only printed in bulk. Even if you could somehow manage to overcome this obstacle, you would immediately face the first rule of economics – “people face trade-offs” – and struggle to decide what to sacrifice, in order to achieve your end goal. Then, at exactly the right time, the Ozalid printer comes along and saves the day. What you would write and how many copies you would publish is now totally up to you, and the amount of toner you can afford. Then, the punk wave also appears and crashes over the popular culture.

Punk is received as a new aesthetic and a philosophical movement. This will actually determine whether what you print at the Ozalid shop is a photocopied magazine or a fanzine. After all, not every photocopied magazine is a fanzine. Those who are not a part of the culture often perceive fanzines as “amateur media.” However, fanzines claim their space by rejecting the outdated and tiredly “professional” qualities of the established media. What the “professional” never gets – the fact that censorship, standards and limitations kill creativity – lies at the foundation of what fanzines are.

That is why the “professional” always follows the underground publications from behind, both visually and culturally. Alright, enough digression…

This was more or less the period when I started to publish my own fanzine. No one wrote about the bands I liked, so I decided to do it myself. I was mostly listening to female bands such as Hole, L7, Babes in Toyland, Bikini Kill, the Gits and 7 Year Bitch, and I only wanted to write about them. Influenced by hardcore and anarcho-punk’s international culture, local fanzines back then used to feature anti-racist and animal rights discourses, but women’s and LGBTQ rights were ignored. I wanted my fanzine to be feminist.

Then, there was the question of format. Since the 1990s there were strong stereotypes in Istanbul regarding format. Some veterans said, “Fanzines need to be in A5 size. People who print in A4 are trying to emulate mainstream magazines.” On the international scene, however, you could find all sorts of formats. I said, “The bands I like were never featured in any of your fanzines, I have a lot to write about and it won’t fit A5.” Also, it was no one’s business! If I wanted, I could have printed my fanzine on 50x70cm paper. Actually I really couldn’t, because the Ozalid shops back then did not have the necessary equipment for such prints and some of my friends would probably hunt me down for wasting trees. So, I settled for a 36-page A4 zine, and named it Inhuman Interest Dept. That is the backstory of the first local women’s music fanzine.

The origins of such cultural phenomena are usually as simple as that. But taking root requires continuity. In the way I have described them, fanzines shaped around a cultural movement began to disappear on this side of the world around the mid-2000s. The increased possibilities of expression in a digital world, as well as easier access to information certainly played a role in their demise. Yet, fanzines – outlets of expression that are as easy as singing a song or playing an instrument – are still a valid form. As they say, it is not important what you get and from where, but how you put it all together.

*This article was created originally for Red Bull Music Festival’s official magazine “The Note”.