From the edge of the society: Masaru Tatsuki

“I think I was a child who always had doubts about ‘society’.”

Interview by Leyla Aksu

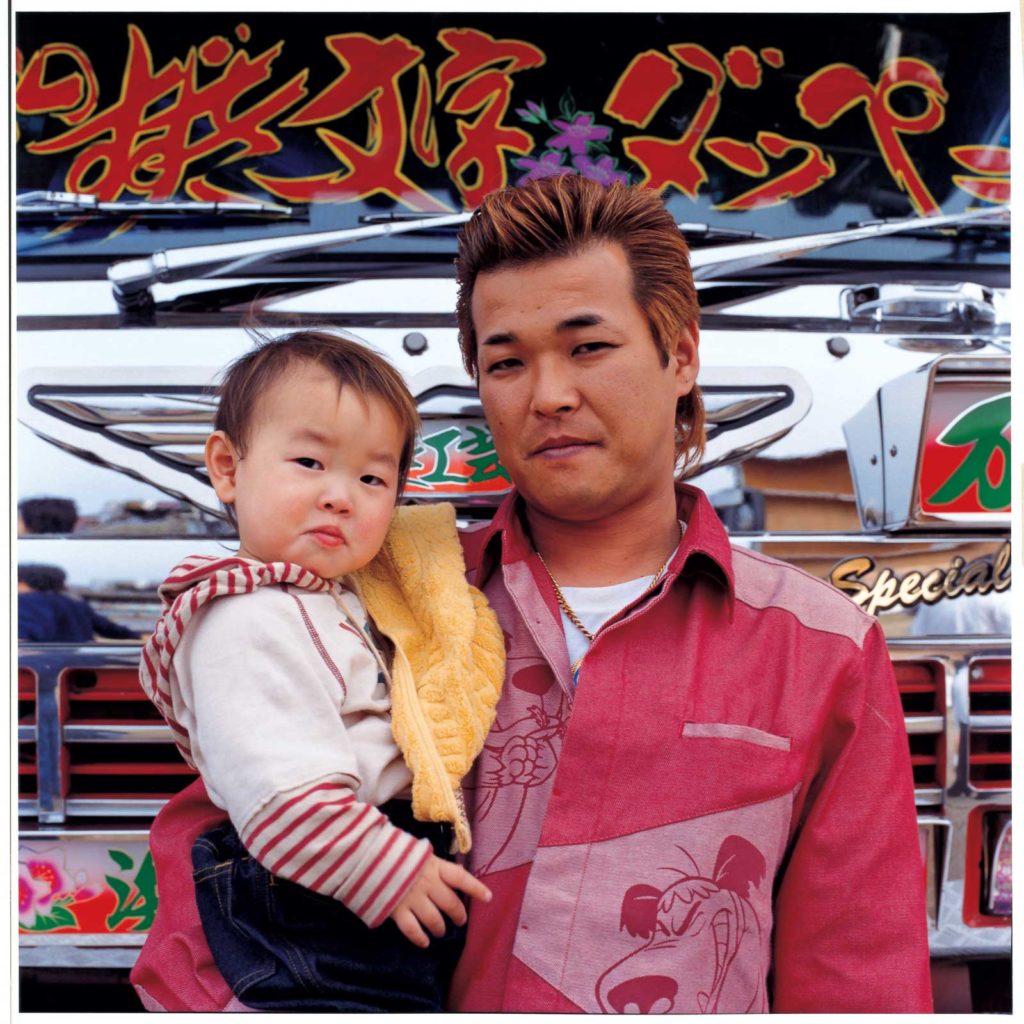

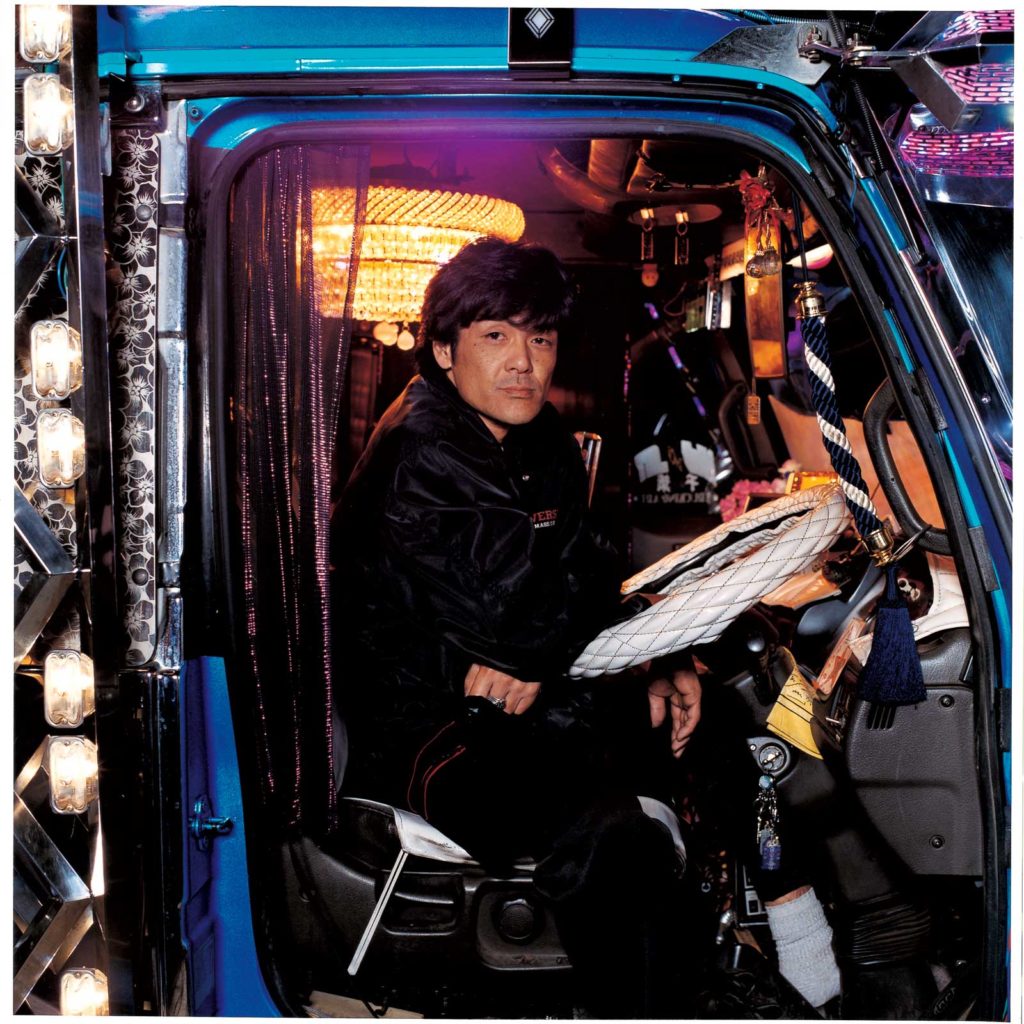

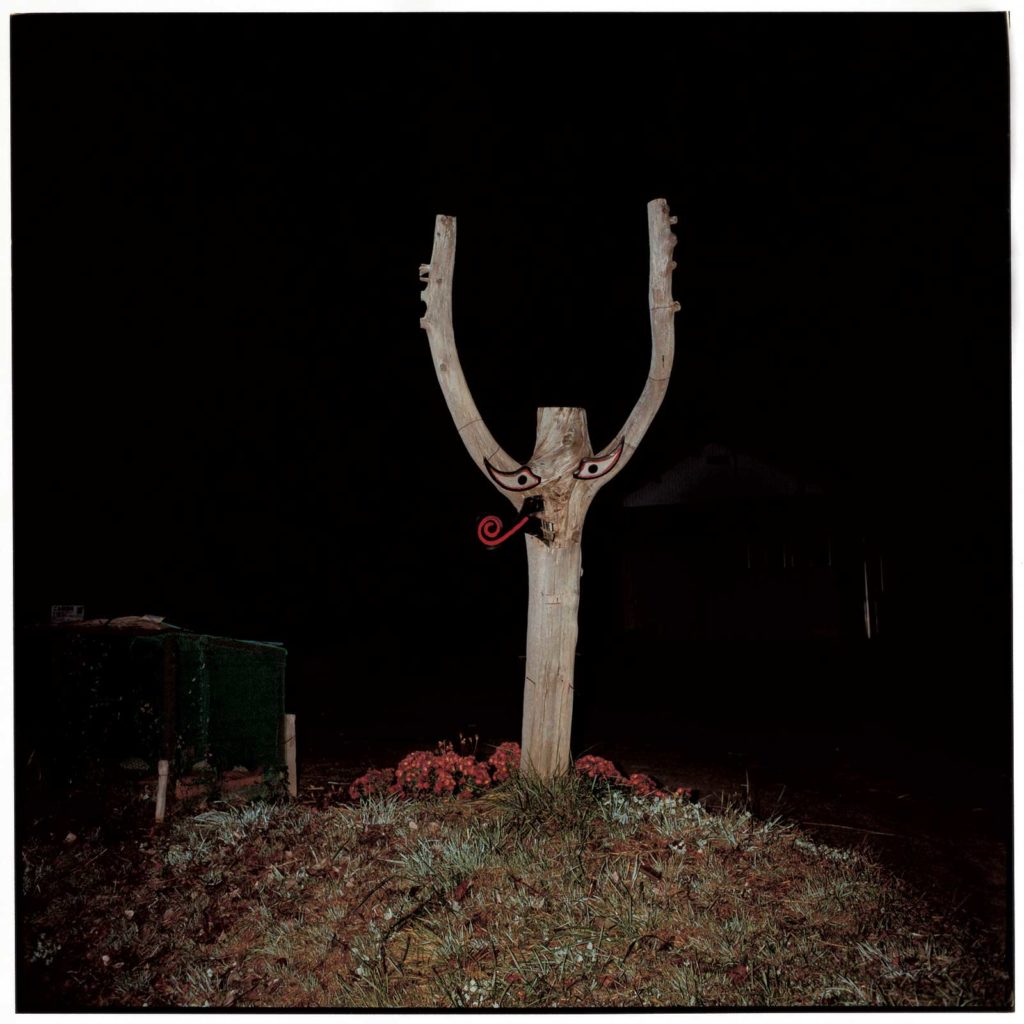

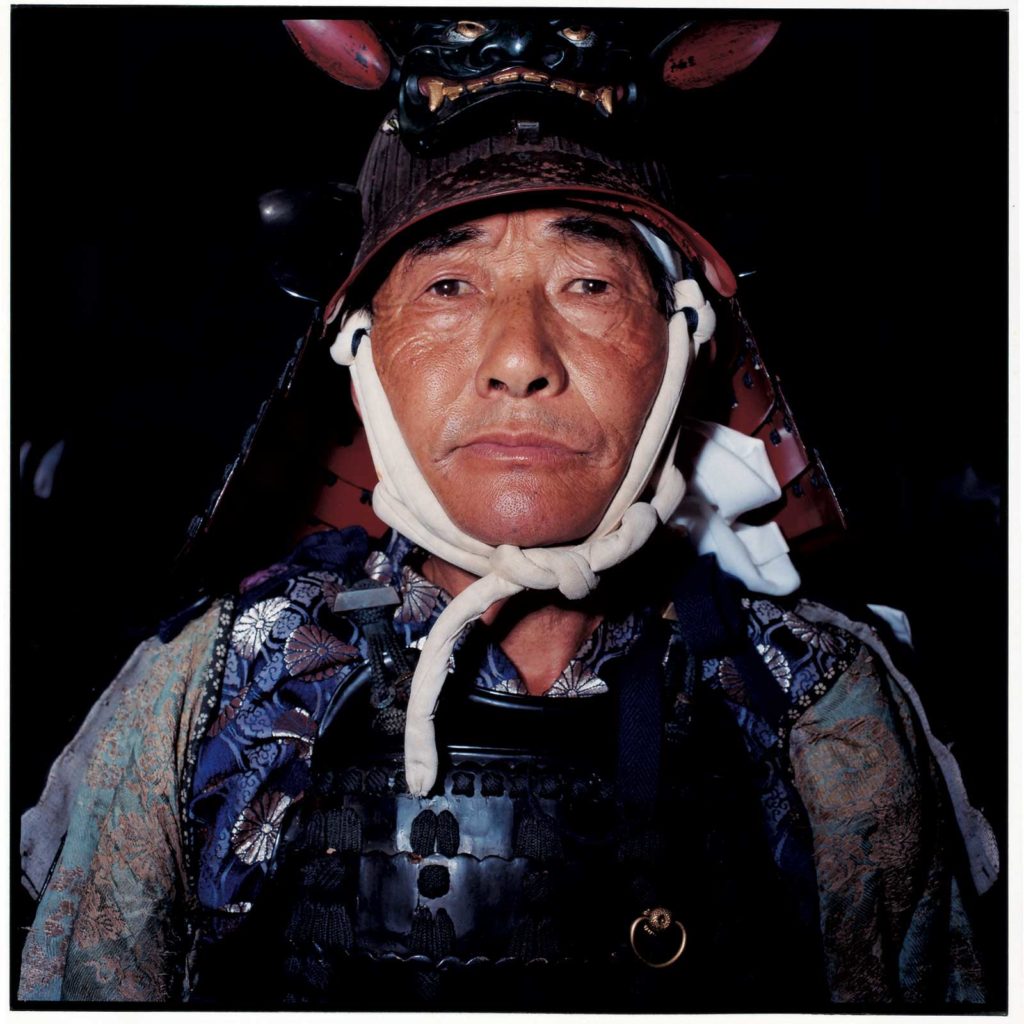

Japanese photographer Masaru Tatsuki aims to understand people, traditions, and the things we leave behind in the face of rapid change. The artist’s photographs focus on those living on the edges of society and his austere compositions introduce their lives without adornment. While his “Decotora” series, completed in 2007, focused on the tradition of decorated trucks in Japan that glisten like holiday lights in the night sky, his following series “Tohoku” was centered on the rural way of life in the region. Masaru Tatsuki is here to tell his story.

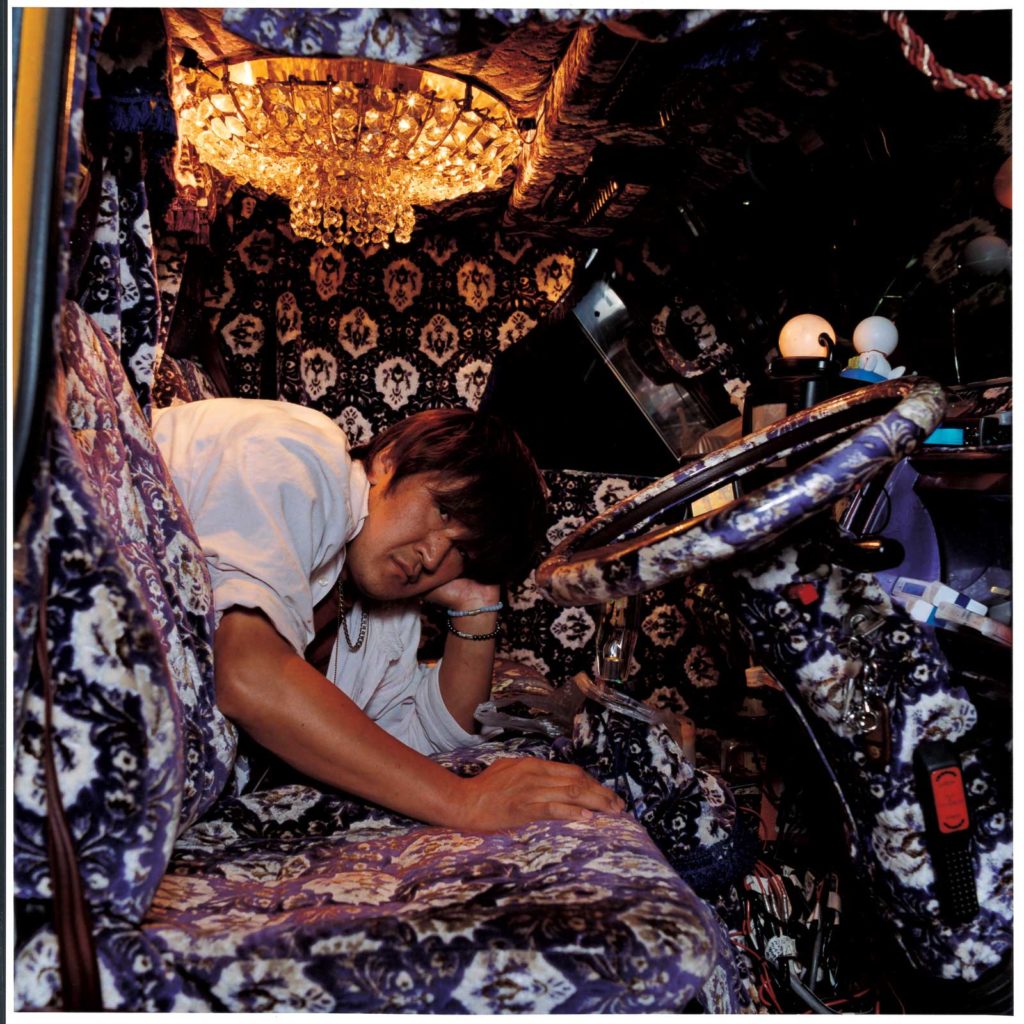

Denshokumaru; Driver Mr. Shimizu, Behind A Wheel, 2005, Tokyo

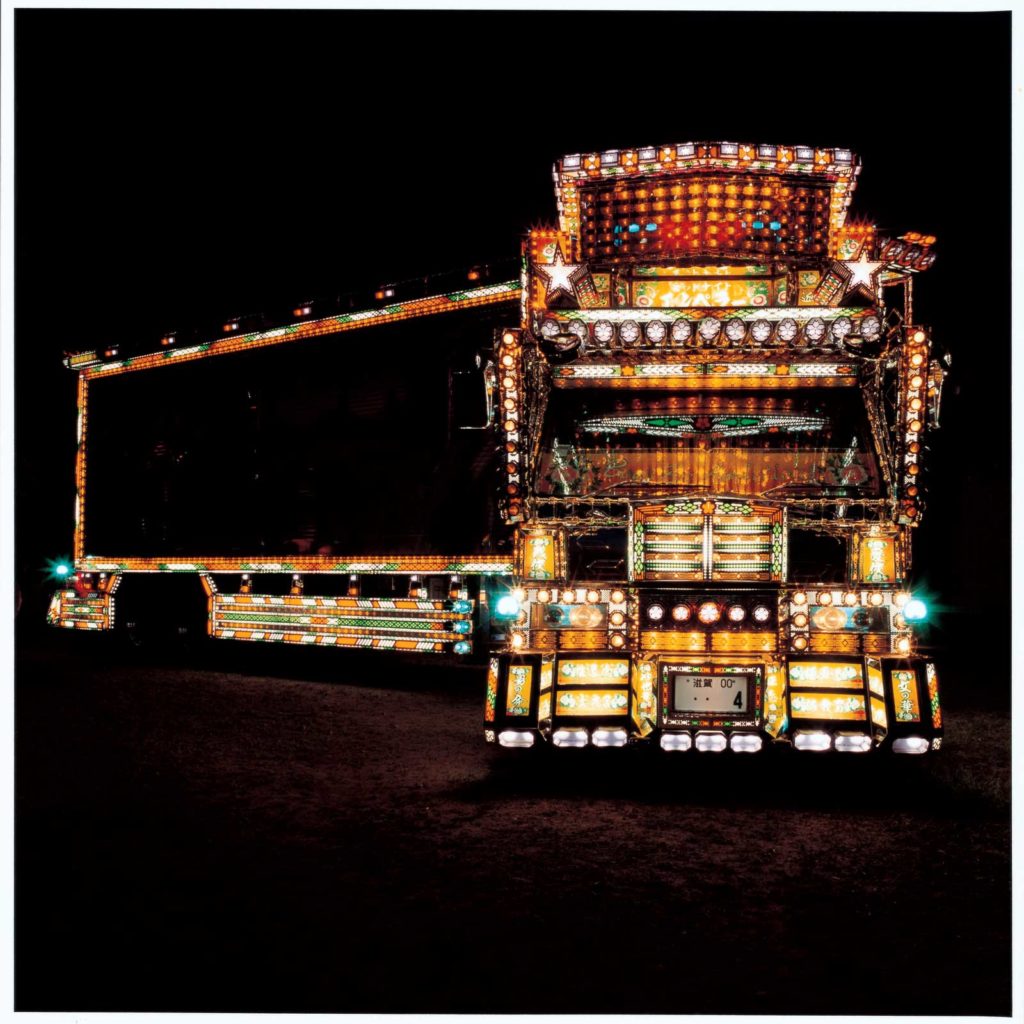

Midnight Emperor, 2002, Shiga

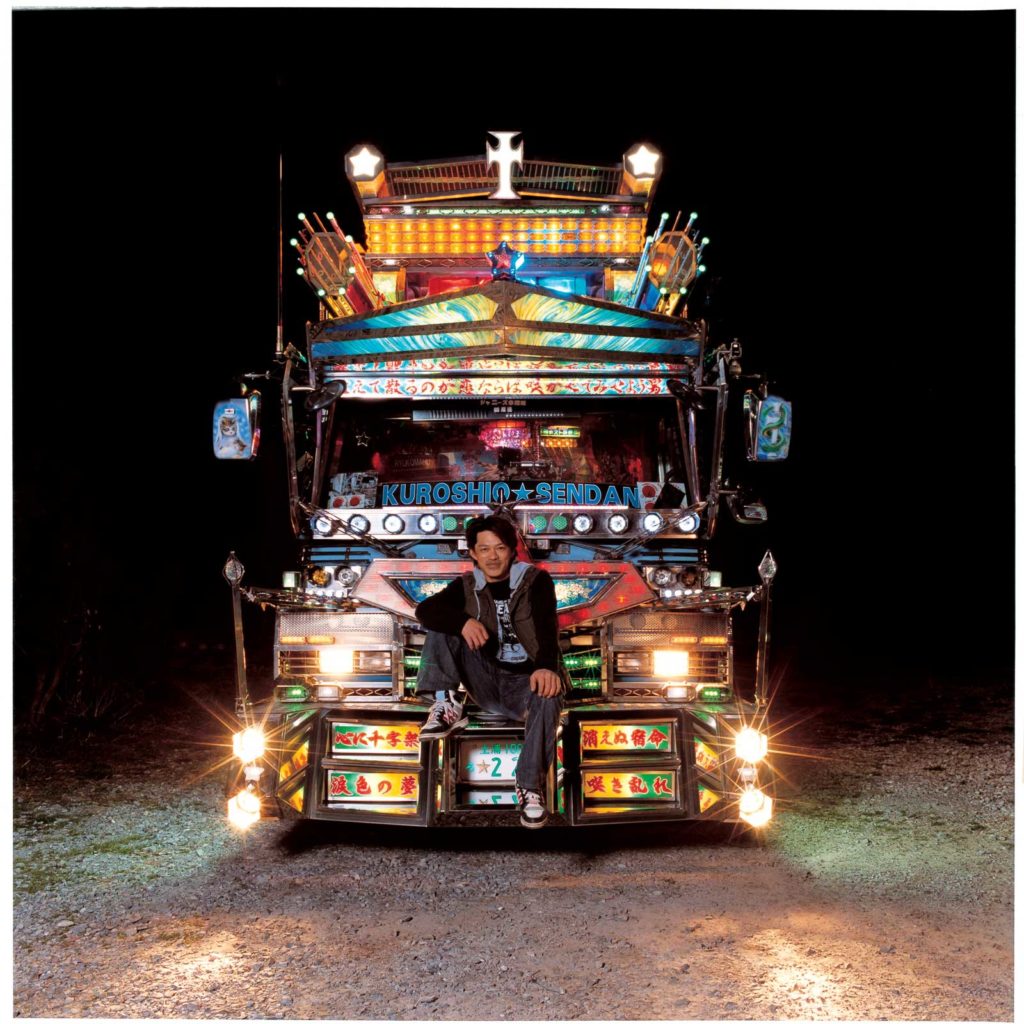

Ryukomaru; Drivers The Miyauchi Brothers (Younger Brother), In Front his house, 2004, Ibaraki

What first drew you to photography? When and how did you begin taking photographs?

I wanted to get a movie-related job for a while because I had loved movies since I was a kid – although almost all were Hollywood movies, which were simple and easy to understand, and many children longed for. Instead of getting into university, I worked at a small film production company in Tokyo after I graduated from high school. Even though working there was fun, I found another possibility attracting me a lot when I stopped by a bookstore during my lunch break. That was the photo-book Diane Arbus by Diane Arbus. Her photos reflected her attitude, and she found her way deep into society and community with a camera, and seemed to encourage and enlighten me to be a photographer. The movie-related work was what I really expected, however, I quit the job in only a year and decided to be a photographer intuitively.

I think I was a child who always had doubts about “society.” In Japan, for example, many people tend to think that success in society was to get into a high-ranked high school and university, and then work at a major corporation, get married, buy a great house and a fancy car. I had been having doubts about this situation where something forced in society leads people’s lives instead of their own decision-making.

Can you tell us a bit about your creative process? How do you determine your topic or time frame for a given project or series?

First of all, I am Japanese. This is an invariable fact, however, it does not mean that I am bound by nationality. I just focus on the place where I was born and I am still maintaining close ties with.

The most important thing when I find a theme for my project is that I gaze at and feel my controlled and stiff country from the edge of society. Therefore, I may be able to see and feel people’s characteristics maintained since ancient times.

I believe that the length of time I spend on my project should not be my own decision, and the photographic subject must have the authority in the matter. I am always in the position of being given opportunities to take photos. I definitely have to be conscious about the border between the subject and me. I also have to be patient to wait for the chance to shoot.

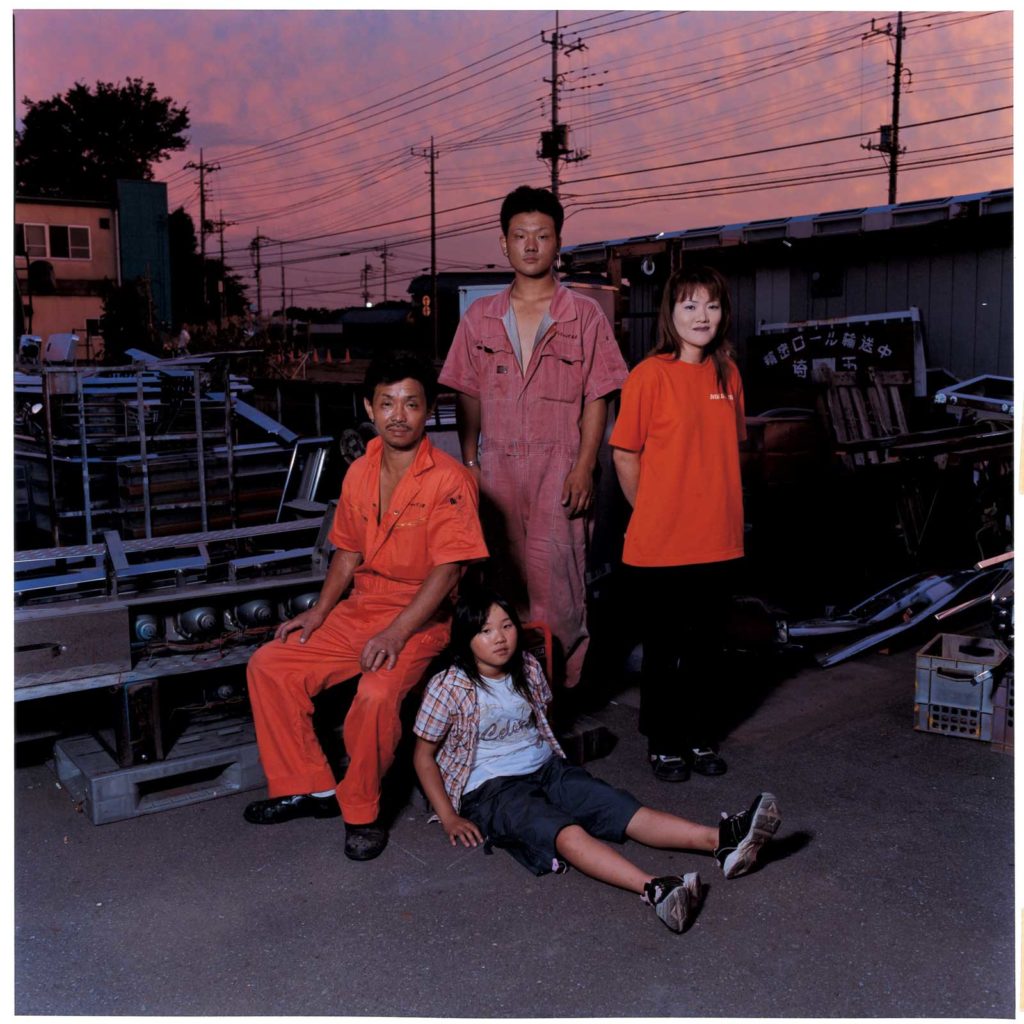

Ishikura Bankin Family, 2005, Gunma

Truck Driver and His Son, 2004, Chiba

Misakimaru: Driver Mr. Tsuchiya, Behind A Wheel, 2005, Chiba

Where did the inspiration for the “Decotora” series first come from?

Speaking of decorated trucks, in the 1970’s, the 10 movie series “Torakku Yaro (Truck Men)” became popular and successful in Japan. However, I had never seen those in real time because I was born in 1974.

I still remember well that I often saw many trucks running on national highways with roaring sound. I just really marveled at seeing a decorated truck for the first time. After a while, I understood the drivers’ pride and sentiment was inhabited in their decorated trucks, so I started shooting those.

The decorated trucks not only create a high contrast against the dark night sky, but with their drivers as well; you describe and reconcile this divide by describing them as an expression of pride. How does that translate into the photographs themselves?

I believe that there is something in common between the trucks and the drivers that I had met. The high-contrast image of the decorated truck dazzlingly shining on the road at the dead of night is a mirror of the sweat reflecting sunlight on the face of the truck driver, who is surviving in an extremely harsh social environment. Both are aesthetic phenomena that I should have depicted.

You started taking photographs for “Decotora” in 1998. Did you observe any changes in the practice or your view of the series itself over the course of your documentation?

Even though I have not published this, I met a truck driver, who knew the real nature of the job, and took photos of him. In addition to the shooting, I often helped his work. I unloaded tons of cargoes from his truck and assorted them again and again. That is, I have been a photographer, but on the other hand, I have realized that I had to get into the society of the subject in order to clearly feel its reality. In other words, it was important that I didn’t grasp the subject as a specific entity, but perceive it from within the subject’s environment.

A Tree with Attached Wyes, November 2008, Tono, Iwate

A Warrior at the Soma Nomaoi, Festival, July 2008, Minami-soma, Fukushima

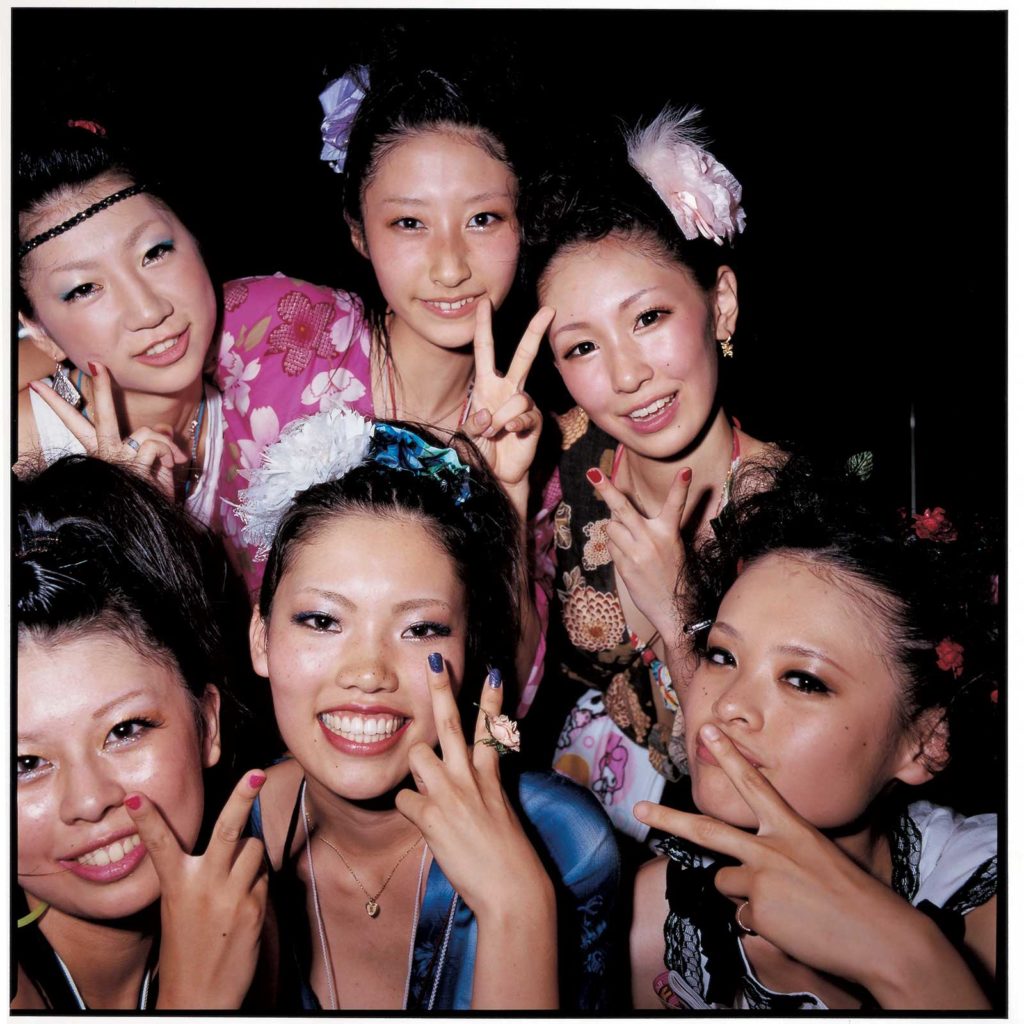

Female Dancers at the Tachineputa Festival, August 2010, Goshogawara, Aomori

Can you tell us a bit about the impression your first trip to Tohoku left on you as a 19 year-old?

I vaguely thought that I wanted to photograph portraits when I was 19 years of age. The reason that Tohoku fascinated me was that I wanted to understand if there were people and landscapes related to the local faith and tradition barely continuing in the rural area, very far from the urban side where I was living. I could not find those kinds of phenomena deeply then, however, I strongly remember and never forget that I felt something unconquered in Tohoku.

Ogamisama, September 2007, Kesennuma, Miyagi

Hands of an Itako from Mt.Osore, July 2006, Mutsu, Aomori

Suneka, January 2010, Ofunato, Iwate

You mentioned that you had to get involved with the community in order to gain access and photograph them. Can you tell us a bit about this process?

At first, the important thing is to lend an ear to the people and subjects. In addition to listening to their story, the more important thing is to make sure we “smell” each other or I should let people know where I am coming from in the first place because my existence is unnecessary in the subjects’ lives.

When you are slowly allowed into a community in such a way, does it have an impact on what you choose to photograph and how you capture it?

I have tried to not be a specific existence, but a close family member for the people who would be subjects of photos. For example, when I sat around the dining table and ate dishes like a family member, I could unexpectedly find something important in their casual conversation.

You have talked about the process of urbanization and change in Japan in contrast with the continuity of landscape and tradition. How do you feel the series embodies this stance?

I have been seeking the answer, for example, to the contradiction between urbanization and traditional succession, from the edge of society, at the bottom of the social pyramid or unconquered rural area. We, civilized human beings, seem to leave behind numerous traditional customs, creeds, and culture. However, through my photos and activities, I would also like to show that we would be able to re-discover the fact that we are now standing on the layers of history, not limited to the Japanese islands.

A Gravestone of the Three-Legged Deer, October 2013, Kamaishi, Iwate

A death of the Three-Legged Deer, June 2013, Kamaishi, Iwate

Can you talk a bit about your experiences in Tohoku since the earthquake? And what do you feel continues to draw you there?

Through my activities in Tohoku since 2006, I felt that my existence became a little bit closer to the locals. Fortunately, all my friends who communicated with me like family survived the Great East Japan earthquake in 2011, but the shape and appearance off the Tohoku that I had seen was totally changed after the disaster. A lot of photographers went there to take photos of the stricken area. Meanwhile, I had no motivation to do so. My basic thought was not changed. I thought that I should have continued to focus on their real lives in Tohoku, not the surface of the event.

I have published two photo-book series “Is the blood still red?” and “Never Again” that focused on the deer hunting in the mountain where invisible radioactive substances, which were brought by the Fukushima nuclear power station accident, poured down a lot. Initially, nobody knew the actual effect of radioactive material so the hunter re-started hunting deer, but I understood that he could not totally enjoy it. Then, in 2014, radioactive material was identified in deer meat, so the hunter returned his hunting gun to the gun shop and has not climbed the mountain to hunt deer since. The deer hunting, which had continued for more than half century in Tohoku, ended.

My main motivation and attitude to take photos is to “understand” phenomena. As long as those would continue, I would continue to take photos in Tohoku.

When you’re dealing with such long-term projects, do you find that they change shape over time? Does this affect your final selection process and how do you know when a series is complete?

The factors that could decide the period to finish my project are not in my hands. The relationship between the subjects and me would tell the time. I would always like to have a conscious awareness of the borders of that relationship. As I mentioned above, it is important to be close to the subject, however, ironically, the project would come to an end when I am too close to the subject.

A Cranial Bone of Deer, October 2013, Kamaishi, Iwate

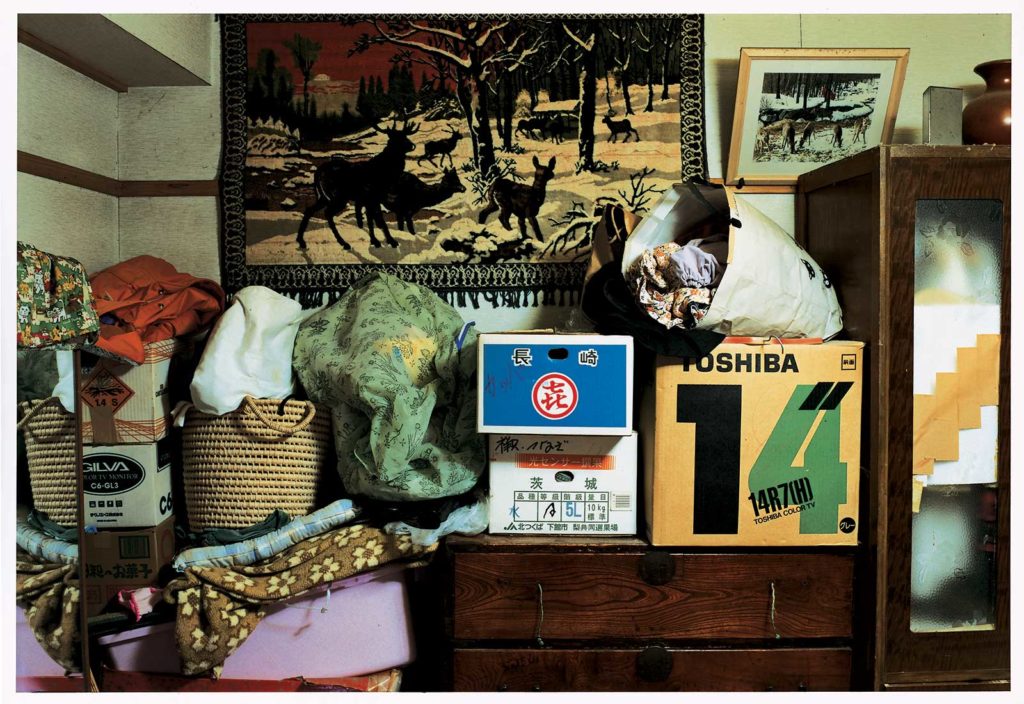

A Rug with Deer Patterns and Objects Carelessly Placed in the House, October 2012, Kamaishi, Iwate

Can you tell us a bit about the process of preparing your work, and these two series’ in particular, for books?

To dive into the subject is the first priority. However much I surfed the net, the information would be things that I can expect. What I would like to know is a thing surpassing my experience and ideas. That is also the thing that I would like to photograph.

What have you been working on recently? Do you have any new projects in the works?

“KURAGARI” is one of my recent photo-books. KURAGARI means dark places or darkness itself. I went to a forest at night to confront the darkness and take photos of deer, which have also been messengers of god in Tohoku since ancient times. I believe human beings sometimes misunderstand that they dominate all creations in the world. There are many places we cannot step into easily and where civilization cannot have an influence, such as the dark forest at night.

I have also been taking photos of a small port community in Hachinohe city since 2014. I have pursued fishery and fishermen, and focused on the connection of human beings to the ocean. Here there is an interesting story. A huge wooden block of a Shinto shrine archway destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 was cast ashore on the coast of Oregon after two years. Owing to the news, I thought it was a great opportunity to reconsider the relationship between countries and people without borders. I have focused on the shore where the sun rises in Japan, and also now, started to focus on the shore where the sun sets in the United States, across the huge Pacific Ocean.