“I do not want my presence to change the scene”: Cheryl Dunn

If New York’s constantly changing spirit can be best described with its streets, Cheryl Dunn might be one of the photography and documentary artists that best describes the streets and creative souls in the most inspiring ways.

Interview by Ebru Bayraktar

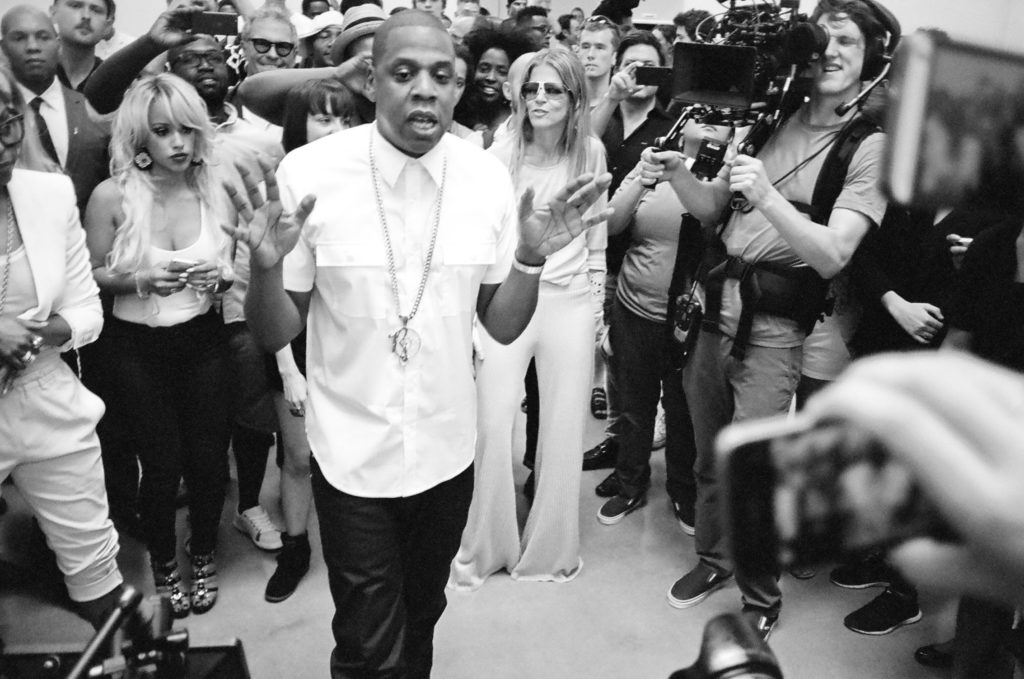

A city’s constantly changing spirit can be best described with its streets. Numerous characters, countless moments and lives intersecting can be best depicted through street photography. Just take your camera and go outside to the street, says Cheryl Dunn. This is exactly what she did as an artist living in New York, the city of extremes. She first stepped into the world of photography in a boxing ring. Her documentary Everybody Street on the 13 street photographers who have become icons of New York (Bruce Davidson, Elliott Erwitt, Jill Freedman, Bruce Gilden, Joel Meyerowitz, Rebecca Lepkoff, Mary Ellen Mark, Jeff Mermelstein, Clayton Patterson, Ricky Powell, Jamel Shabazz, Martha Cooper and Boogie) lets us witness the change in New York City over years through the eyes of these artists. Bicycle Gangs of New York is another exciting documentary about the New York’s bike gangs; she also turned this documentary into an archival book. We have talked to Cheryl Dunn, who collected the moments she caught in various festivals of the world for over 20 years in a book called Festivals Are Good, about her outlook on street photography, her sources of inspiration and what the future looks like.

‘Everybody Street’ is a truly inspirational documentary. In one of your interviews, you said you like the street photography because it is democratic. Do you think street photography is suitable for any character?

Sure. It has so much to do with how differently we all navigate the world. How we see things and how we interpret what we see. And all of those variables are very different for people.

In the documentary we see all kinds of personalities and styles taking photographs on the street. Different artists obviously have different approaches to their subjects. What is your thing usually? What are your boundaries?

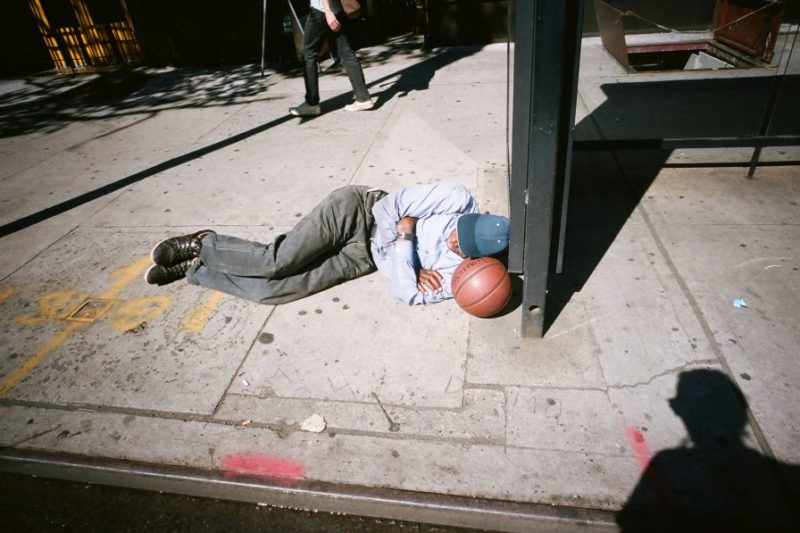

I try not to have someone see me because I don’t want them to alter their behaviour or change the natural scene. But that is hard to do, every situation requires a different strategy. I try to be respectful to people, that is very important to me. I am usually commenting on the human condition or the state of society if I am photographing someone having a hard time. I will pull back if I sense that my actions are making someone feel bad but if they don’t know they have been photographed, then there is no harm done. Sometimes I will talk to someone holding a sign or begging on the street and then after engaging with them I ask if I can get a shot of their sign or something and they usually always say ok.

One assumes you have massive archival footage of various artists, subjects and different topics piled up starting from the early years of your career. How crazy is it?

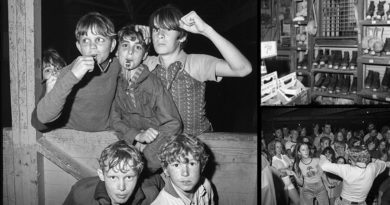

I do have an archive . I don’t know if it’s massive but years do go by and it starts to add up. Now is a time where people come at me for pictures for books of scenes that happened 20 years ago. I’m just glad that I always banged out a bunch of shots at every art thing I went to and that I have my stuff organized and can find it. That is the key!

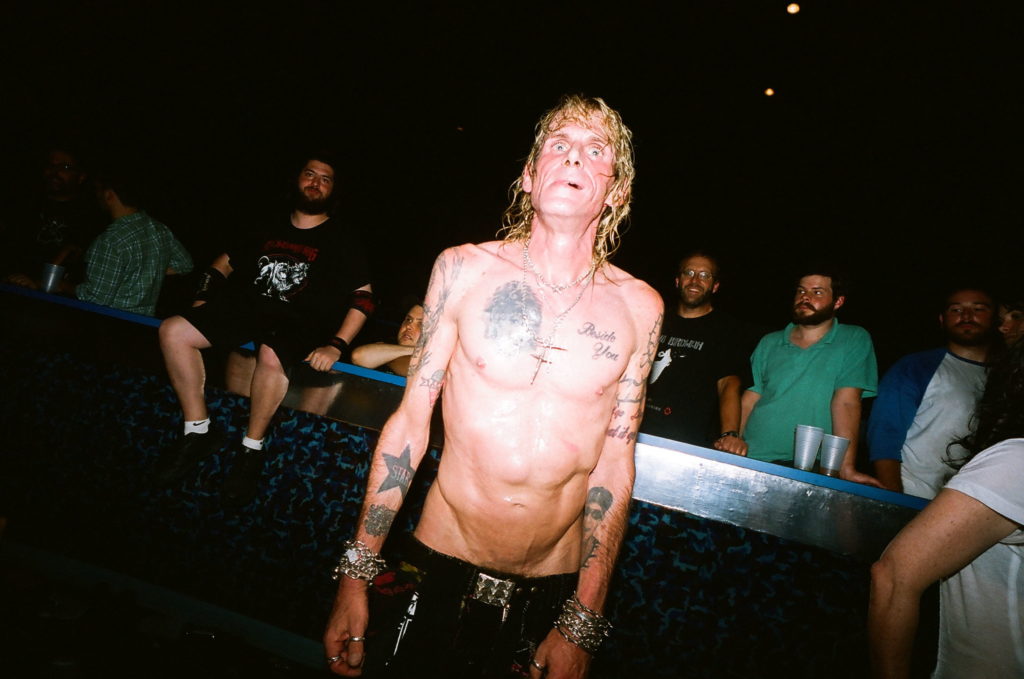

Your latest book “Festivals Are Good” brings together photos you took at festivals since 1994’s Woodstock 25th year anniversary. How have all these years of being behind the lens affected and changed your perception of massive music festivals and the thrill of fans?

I am a participant and an observer at the same time and always looking for shots. So the whole experience becomes a study, and all of these activities I love to do… My perception hasn’t really changed, I just think some aspects of people’s behavior changes when it comes to being photographed but the action of fans sort of remains consistent. Genuine youthful excitement is pretty pure and timeless. I am not tired of watching that excitement and trying to capture its essence.

When and with what motivations did you make the decision to approach this body of work (shooting festivals) as a documentary project?

I started in 1994. I just wanted to go and be able to shoot so I would approach magazines to see if they wanted my pictures and every year I would try to get an assignment from someone. It was just doing something I enjoyed. I think I just go in a direction because I’m curious about it, I strategize how to gain access and then I just study it for a long while. What I will make out of that study comes way later when I feel like I have done it extensively and have the opportunity to make a statement about it and put it in the world as a collection of images .

How invisible are you when documenting and exploring different topics and subjects? Say when you were shooting at the professional boxing ring? Or when you are shooting at the festival area?

I try to stay as invisible as possible, very fly on the wall. I do not want my presence to alter the scene if I can help it.

How do you interpret the change in New York through the eyes of a street photographer?

Change is inevitable, It’s history. I am documenting my neighbourhood in Lower Manhattan where my studio has been since 1989. It is really going through huge changes right now, and that is interesting to me. I think good street photos are about contrasts and conflicting juxtapositions, so the clash of old and new creates and interesting tension.

What could possibly be most certainly different for a woman in street and documentary photography now in New York, than 30 years back?

30 years back to be a woman trolling the streets with a camera was certainly less common and viewed as dangerous perhaps. I had Rebecca Lepkoff in my film talk about this. She said she was in a sketchy part of town by herself shooting in the 1940’s or 50’s and a cop told her she shouldn’t be there it was too dangerous for a woman. She told the guy to mind his own business. As a woman, often people think it is ok to project their fears on you, and I think that is bullshit.

When you value what is inspiring in street photography today, to what extent do you care about photography technique?

I personally care a lot about technique. I have studied and worked on this for my whole career. I can throw it out the window at times but I solidly know it and can call on it at anytime. I know absolutely what my equipment can do, what the light is doing and how that light and my settings will combine to get the shot. The difference in street photography is you have to make all these decisions and choices in an instant and sometimes you just aren’t fast enough…

What kind of an effect does taking a photo have on the psychology of the one who is taking the photo? Does taking a photo have something to do with the desire of holding on to something and keeping it in a rapidly and constantly changing world?

I think so, it does for me. I always am thinking to myself about the precious unrepeated moment that I am experiencing and I must record it, that the moment is super important to capture for the future as proof, as a record, a document. I like to think of this as the documentary arts, or being a documentary artist…

Who did you look up to when you were growing up in terms of photographers, street artists or moviemakers?

Photographers, Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson. Documentary filmmaker Les blank.

What are you working on currently?

TWO documentary features. Both about artists…