In Between Moments: Brian “B+” Cross

Having famously shot the cover image of DJ Shadow’s brilliant 1996 debut “Endtroducing”, renowned Irish photographer, filmmaker, and DJ Brian “B+” Cross arrived in Los Angles in the late 1980’s and started documenting right inside the city’s early hip-hop scene.

Interview by Leyla Aksu

Capturing the absent historical-cultural contexts and the secret alternative histories layered within the music we listen to, renowned Irish photographer, filmmaker, and DJ Brian “B+” Cross arrived in Los Angles in the late 1980’s and started documenting right inside the city’s early hip-hop scene. Following an expanding musical trail to countries like Colombia, Brazil, and Jordan, Cross has since created music videos, album covers and documentaries in addition to his photographs, working with artists like the Freestyle Fellowship, DJ Shadow, David Axelrod, Mos Def, J Dilla, Jurassic 5, Thundercat, Lauryn Hill, Warren G, Q-Tip, Damien Marley, Dilated Peoples, Erykah Badu, and Rza just to name a few. Recently releasing a collection of his work entitled Ghostnotes: The Music of the Unplayed, Cross kindly took the time to talk with us about how his new book came together, his process, the early days of hip hop in Los Angeles, and what he’s been listening to lately.

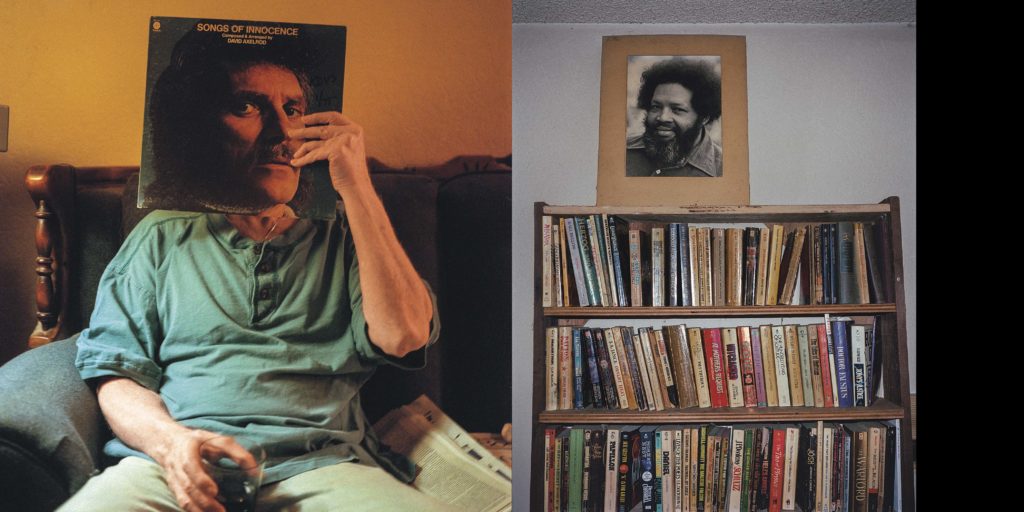

David Axelrod, North Hollywood, California, US. October 1999 and Axelrod home, North Hollywood, California, US. October 1999

So to start off I just wanted to ask how you first got into photography back when you were in Ireland? And when and how did you first start getting into music?

Well in Ireland I basically, you know, I went to art school. I was good at art—whatever that means—and while at art school, really through the work of people that were doing a lot of rephotography kind of work, you know people like Hans Haacke, who was sort of doing institutional critique kind of work, but even, like, Cindy Sherman and more particularly the work of Allan Sekula. I just became interested in photography as a… kind of as a tool, really, at first, for investigating ideas.

I’ve been into music since… I don’t know; I’ve had this sort of weird connection to music since I was very very young. Not really sure, you know, it’s not like there are musicians in my family particularly or anything. I mean, my dad’s kind of a folkie a bit, but wasn’t like I had a crazy thing, but music was—I mean, I guess in the mid- to late ‘70’s, music was a kind of international force, and Ireland at that time was really inward-looking. So music was a way to think of the rest of the world—radio particularly, actually. You know, we didn’t get much pop music on the radio in Ireland at that time, but you could tune into, like, Radio Luxemburg, or if the weather was right, you could get BBC Radio 1. And so it was always like… I don’t know, thinking about other places, I guess.

And ostensibly, yeah, I never really thought of those two interests coming together until I was at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts), really, and while I was at CalArts, that is when the coin kind of dropped. But you know, I went to CalArts to study with Allan Sekula; I went to the graduate photography program there. And while I was there, sort of through the intervention of this other professor Mike Davis, who was writing a kind of famous book about Los Angeles at the time, he encouraged me to make photographs of hip-hop in L.A., and, I don’t know… It was kind of like, I was young, and you do things for reasons that—It’s like, “Well okay, that’s interesting, I’ll give it a go.” And then you don’t think it’s going to change your life, but that’s kind of what ended up happening.

Getting to the book then, though this is discussed a little in the text, can you talk a bit about the concept of “ghostnotes” and how that correlates to the conceptualization of the book?

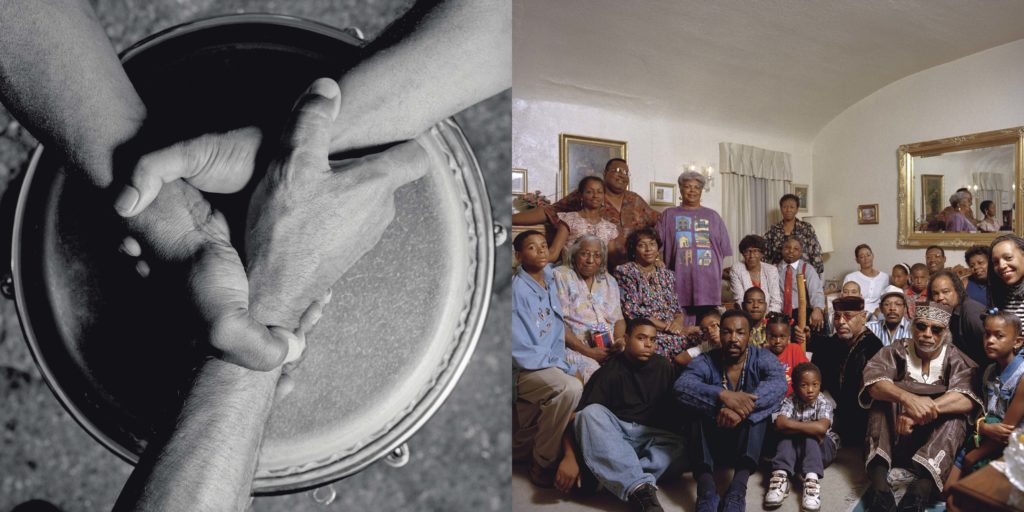

Yeah, so I’ve always been interested in the way that photographs run together, you know? Like the way sequences of photographs work? And I’ve always spent a lot of time thinking about that kind of stuff. And then, at the same time, obviously over the last… Well, I mean, when I first started thinking about this, it had been like 10 years, 15 years that I’d been making photographs about music and about music and culture and how those things function in terms of building communities and bringing people together in different kinds of ways, exploring different kinds of histories. And around that time, I think it was, Nu-mark—I mean, I can’t remember for sure, but I know he had the VHS—There was this great VHS instructional video made by Bernard Purdie, the famous drummer, where he talks about his “ghostnotes,” and I just remember thinking, like, “Well, that’s a fucking cool phrase,” you know? And it kind of describes what photography does somehow. And that was the beginning of it. Then, over the years, obviously from finding more out about drummers and working a lot with drummers, making Keepintime and Brazilintime, and thinking about how history works, and how things are present even though they weren’t really brought into being—I mean, they were just kind of there, they applied themselves—and just sort of imagining all the metaphorical possibilities that existed in the turn of phrase. And as a name I used it first in, I think it was like ’98 or ’99. I had a show at New Image Art, a sort of small but important gallery out here. And, it stuck!

And so I always had this notion, but I’d been warned by other photographers, you know, if you do a book of your photography, don’t let it be like a kind of greatest hits, like all the famous people you photographed, don’t let it drift into that; that the work should stand on its own, and it should— It has a meaning, and you need to point to that. So “ghostnotes,” it’s always been there, it’s always stuck, and it’s always kind of functioned as a very nice way to sort of bring together the kinds of things I’m interested in as far as history, as far as place and time, and as far as this kind of accidental quality of photography, you know? This notion that somehow these moments barely existed; I mean they only exist in the rear view mirror. Like, I don’t know that necessarily if you stood in the room looking over my shoulder that a lot of these photographs would have even been noticed, like the look, that casual glance, the whatever… You know, the kind of thing that photography does is sort of an in between moment.

Feira de Caruaru Caruaru, Pernambuco, Brazil. February 2012

From left to right Beni B, Chief Xcel and Lyrics. Born at Records downtown, Sacramento, California, US. May 1995. This is the cover of “Endtroudicng” C by DJ Shadow.

Sound system repair Jamaica. January 2012

You talk about your work in terms of creating a map and hip-hop itself, through its processes of creation, as engaging with hidden alternative cultural histories, which positions your work as a direct visual continuation of the music itself. Can you talk a bit about looking at your work in that way, how that affects your decision of what and whom to photograph, and the permanence photography as a medium within that?

Basically, the thing is it’s not like I sat down one day and thought this through as a kind of research arc. I didn’t, you know? There’s this phrase that I use in Brazilintime, this documentary that I made, where it says, “A documentary is a film that has some notion of beginning, but never a notion of an ending.” And it was a project that began in that way, like I didn’t really know where I was going; I didn’t know about Colombia, for example, I didn’t really know about Brazil, and for sure didn’t know about Ethiopia, or the way those kinds of things would play a part. But then, at the same time, I felt that the research was sincere, it was something that I was deeply concerned with, and it was something that was prompted by the music. Like, I don’t know about your experience, but in my experience hip-hop—it made me want to go find the records being sampled, it made me want to understand what could allow certain kinds of utterances to take place. And I’m thinking like, the kind of research models that I’ve been inspired a lot by. Let’s say, Grail Marcus, for example, wrote that book Lipstick Traces; years and years ago I read it. I remember at the time thinking there’s something kind of wonderful about that, in the sense of Johnny Rotten (John Lydon) says, “I am an anti-Christ,” or whatever; where did that come from? What’s the history of that? And those amazing James Brown almost non-lingual utterances, it affected me in the same way. I was like, “Oh my god! There’s a whole level of experience out there that reaches me in my body, but that I have very little way of trying to understand.” Of course, as you go along you realize that it’s not simply a matter of understanding in a kind of rational or Western way at all; actually, it’s kind of prompts the opposite.

So that’s how it started, and then there’s the kind of chance discovery. You know, there’s being in a record store in Miami at the end of the ‘90’s and finding a big stack of [Discos] Fuentes records for really cheap that were all sealed, and kind of taking a chance one ones that said, like, the word “Afro.” [Laughter] And just being like, “Afro records from Colombia?! I wonder what the fuck that is!” Getting home, and then liking it, responding to it, but not really having a way to understand it, in terms of, like, how could this have happened? And then just doing the historical work kind of upside down.

You know, the sad thing about the academy—which I teach now as well, so it’s different—but very often the academy is very slow in terms of certain areas of study. We spend a tremendous amount of resources and a tremendous amount of hours researching Western-European classical music. We haven’t spent a tremendous amount of hours and resources researching and understanding the roots of popular music, which comes from Africa. Certainly there are scholars that have done that work, but relatively, we don’t put [in] the same kinds of resources. And to me it seemed like I needed to know. Basically, I needed to understand or at least needed to put myself there. It’s whatever It’s Not About a Salary… was about in ’93, about the local scene here and understanding where people were coming from. I felt after, my takeaway from working on that project was, “Fuck, there’s a lot of stuff that I don’t know that I need to go and think about and pay attention to.” And I guess that’s Ghostnotes; in some weird way, it’s the product of that. It’s the product of me scratching my head and going, “Holy shit! This is a lot bigger than I ever could have imagined and a lot more important. And somehow I need to find a map into it,” you know? But, of course, the map is not cognizant of national borders in many ways; it is sort of meandering, and as the crow flies, and as the record travels. You know what I mean? It’s not rational or linear, and I was just putting one foot in front of the other for a lot of it. But by the end I kind of came to a— You know, I went to Belém in the north of Brazil, and it felt like an end. Then Kendrick [Lamar] put out To Pimp A Butterfly, and that felt like it was another semi-colon that was helping me with a full stop. There were things that happened that were like, “Yeah, this feels like an end.” And so that’s it.

As you just mentioned your first book, looking back at It’s Not About a Salary…, what did you utilize from that experience while putting Ghostnotes together? Was there anything that you learned that you wanted to avoid?

Well, I felt like it was important this time for me to… You know, there’s this kind of, like, the humility of realizing you’re not a writer? I mean, first thing. [Laughter] And then there’s realizing that I was unable to push home as clearly the notion of that book as a photo-essay, as well. So that was really important this time out. But I also felt like, when I agreed to make that book it was because I felt like something like that needed to exist, and there was a clock ticking. Whereas this project, I didn’t even show it to publishers until I felt like it was coherent in terms of having a beginning, a middle, and an end, and it had a kind of form that I was happy with, or whatever. So, I could have spent another five years on It’s Not About a Salary… happily, you know? I couldn’t have afforded it, and I was kind of too young, really, when I did it. You know, it’s a flawed text. It’s important that it exists, and it did what it was supposed to do. It did open the door for a number of folks that came and did the real work; people like Jeff Chang, for example. But this time it needed to be more on my terms, I guess.

Then what was that long process of finally getting Ghostnotes together like? How did you decide on the scope of it—what to include, even the specific pairings, the layout, who would write the essays? How did it all come together?

Okay. So basically, I had been shooting happily like a maniac for 20 years, and I was literally just following my nose, my ears, and my heart. And just to be clear, a certain percentage of the work in that book was made from things that I got paid to do, and I still have a somewhat successful career as a music photographer. What I would do was, whenever I got a little bit ahead, I would try to be like, “Okay, it would be really smart now to just try to go to Ethiopia.” I’ve always been on this thing, like, if you need to understand something about the Wu-Tang [Clan], then you need to go to Staten Island, and you need to go by the projects, and you need to walk there, and you need to listen to the music there; and see how it hits you there, see how it feels in your body there. You’ll have a different understanding. You know, driving down Crenshaw with a bunch of weed and a 40-ouncer or some Hennessy in a red plastic cup is a profoundly different experience than wherever you would be in the world. [Laughter] I think there is something instructive about doing that. And so whenever I had the opportunity, I would go and shoot in places and try to invest in the, sort of, larger project, right?

So I ended up with all this stuff that people had never seen. Like, a lot. There are a lot of negatives here. And through some work with a famous street artist, I ended up with a painting that was worth a lot of money in my house that… I don’t know, I mean, the things that are worth things to me in my house are more like the archive, the books, the records, that sort of stuff. The painting was kind of freaking me out. [Laughter] It was worth too much money. So I decided to get rid of the painting and make an investment in the archive properly: I bought a really good, expensive scanner and started in 2012, and myself and my assistant scanned approximately 4500 MB. And that was just me going through the archive, envelope by envelope, and picking things out. Obviously some of the stuff were things that I already knew, but then there were a lot of things that I found that I didn’t remember; things that at the time maybe weren’t as valuable as they are now, or at least that I think they are now. And so I ended up with about 4500 scans, and then the play started.

I’ve made version of this book to show in exhibits previously, where I took chunks of the archive and made essays out of it; so it’s something I’ve been doing for years. The difference with this one was, however, that I did it digitally, which is the first time I’d ever tried that. And it took a while, you know? I still prefer to do it paper and scissors, to be honest. Doing it digitally requires a different kind of headset. And so I worked away, worked away, worked away and then got it down to a version of the book that had about 450 photos, which is this kind of mammoth, fucking thing which operated, like, horizontally, vertically… It was just a fucking behemoth of a thing; it was a gnarly fucking book. Then I started to reach out to people who I thought might be interested, and weirdly enough, none of the people that I reached out to were interested! But out of nowhere, I got a cold e-mail from University of Texas Press. Obviously I had the PDF, and David Hamrick really enjoyed my work from before and then saw this fucking massive thing and was like, “Okay, that’s cool… but the average photo book has 85 photos in it; you have 500-and-whatever. So you need to get it down to—at least let’s aim to get it close to 200.” And pretty fast I got it down to 225 or something like that? Then we had a little bit of back and forth, not much, and then it was done. There was a bit of finagling; I thought I’d lost Lauryn Hill for a while, and then [Erykah] Badu came along, and then Lauryn came back… So there have been a few bits of finagling; there have been a few people that I lost that I’m a bit bummed about. Like Quantic’s not in there, the Roots aren’t in there, you know, Old Dirty [Bastard] is not in there… but they can be Volume 2, or, I mean, I hope this isn’t the last photo book I ever do, so we’ll see. Anyway, I finally got the book in my hands this week, actually just two days ago. And yeah, I don’t know. I’m one of these people that I’m only going to see the mistakes for a while. But it’s real; it’s done. I can’t believe it.

It must be a great feeling to actually hold it.

It’s… pretty weird. It’s kind of surreal. It’s a bit anticlimactic; I have to be honest. There have been so many versions, you know? But anyways… Yeah, I’m happy.

J Dilla, Clinton Township, Detroit, Michigan, US. 2000

Leon Ware and George Clinton, the Mayan Theatre, Downtown Los Angeles, California US. December 2012

The Watts Prophets, Watts California US. October 1996 and The Watts Prophets with Father Made Hamilton’s family, Los Angeles, California US. October 1996

Thundercat, Los Padres National Forest, California US. 2015

Wilson das Neves, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. October 2002 and Vai Vai (Grêmio Recreativo Cultural Social Escola De Samba Vai-Vai) Sao Paulo, Brazil. October 2002

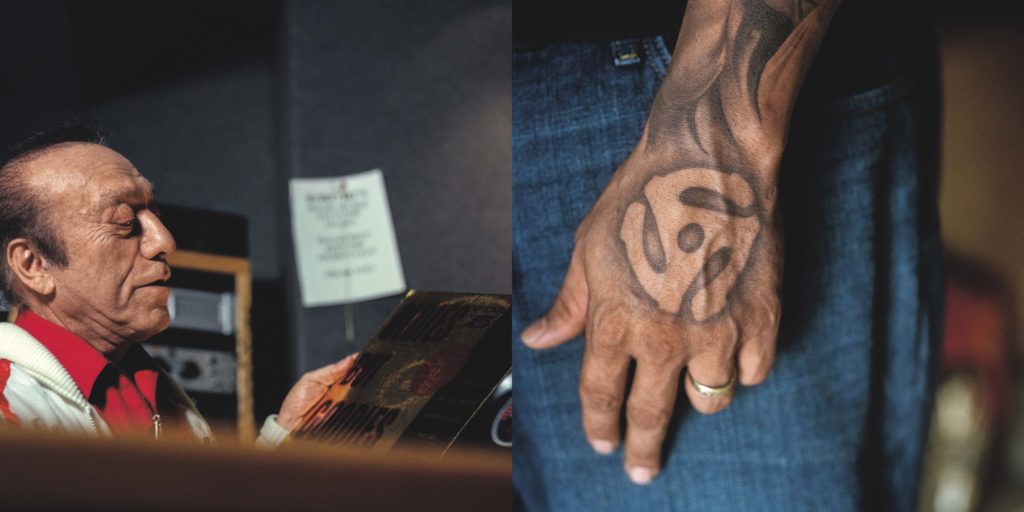

Sound Studios Hollywood California US. April 2010. Laboe is credited with coining the term “Oldies But Goldies” and recorded Dyke and the Blazers in the late sixties George Miller. Los Angeles, California, US. February 2010

So to talk about your work that people might be more familiar with, what was it like getting involved in the hip-hop scene in L.A. back in the day? Coming from the outside, what was that like? And how did that initial experience shape your approach to photographing scenes in different countries and locations?

I think my root in this is coming from that scene with people like the Freestyle Fellowship, the Pharcyde, Ava DuVernay, Horace Tapscott, Billy Higgins, and under the influence of people like Reggie Andrews and Ben Caldwell, Billy Woodberry… I mean the list goes on. But what I would say is they’ve been extraordinary. They were extraordinarily generous with me. I think they were a little bit… I mean, they hid it very well, but… [Laughter] Actually, I think there are probably a few of them that are still looking at me side-eyed sometimes. “Fucking how? Where did this fucking guy come from?” But ostensibly, I learned my stock-in-trade from listening and watching and figuring out what works with those guys, really. I’m eternally grateful to them, and I always try to rep for L.A. in that sense. Obviously I’m Irish, so that important too. But as far as this part of my life, those guys were the ones that taught me what’s the appropriate—and Eric Coleman, actually. Eric came into my life around the end of ’96, the beginning of ’97, and he was really very helpful as well. But it’s with those sets of rules that we then went out into the world: Like understanding when it’s appropriate to photograph, when it’s appropriate not; when it’s appropriate to talk, when it’s appropriate to not; when it’s appropriate to listen; when it’s appropriate to put the camera away completely… Just the kinds of rules and regulations of dealing with communities like this, underrepresented communities that are very often the last people to gain access to resources, and being sensitive to those kinds of things. Which I think we’re getting a little better, but you know, it’s slow. It’s slower than it should be. So yeah, it was from those guys, and Sekula, of course, and Mike Davis, Michael Asher, those kinds of dudes; that’s where I figured out how to do this really. I mean, coming from Ireland and being from outside in some small ways was useful. In that it was difficult to place me, you know? Like the L.A. thing is, “What high school did you go to?” Whereas I went to St. Clements, you know. Like what the fuck? In Limerick, Ireland. And nobody even knew where that was, so that was useful. I had a kind of weird accent, though obviously that’s kind of gone away now, though it’s equally weird, but it’s a different one. But my ability to negotiate my way into that sort of situation and to walk with the kind of humility you need to be able to walk with to do this kind of work, I learned that from the Black Arts community in Los Angeles. And by that I mean from Horace Tapscott on down to the Freestyle Fellowship, the Pharcyde, Cyprus Hill… all those guys. It’s from working with them that I learned how to walk, really.

That’s amazing! Well, looking back at that era of West Coast hip-hop, from that vantage point, what did the future look like to you then? And looking back at those images, what do you feel is their relevance today – culturally, aesthetically, or personally?

It’s very weird because at the time there was this kind of, uh… I mean I firmly believed that what we were doing in L.A. was the most important thing—period [Laughter]—in the country in terms of the music and that L.A. had something peculiar and unique to contribute in terms of dance, in terms of music, in terms of the relationship to the Black Arts community, in terms of all the kinds of things that the best of what people like the Freestyle Fellowship represented at that time.

And as far as the future, I never really thought of it… Like, I didn’t see The Chronic coming, you know? I didn’t see Diddy coming; I didn’t see bling coming the way it did, really. I didn’t really see pop being the end game potentially, and in some respects it isn’t, but that kind of stuff… If I did, I’d be much richer, you know? [Laughter] And working with Jimmy Iovine or some shit, something awful; putting some bad shit out in the world, somehow buying up university campuses or something, you know? [Laughter] But I was much more interested in, how do we get college radio? You know, simpler things. How do we get real spaces where this kind of cultural stuff can happen, where it can be supported? On a small scale, underground kind of stuff. So to look back at it now… I don’t know, there’s something kind of wonderful about being able to say, “You know what? It doesn’t need to be all about Snoop and N.W.A.. They can be there! But so can the Pharcyde and the Fellowship,” and to be able to formulate that story in the way that I could. I mean I always felt like the book needed more L.A., even though there’s a lot of L.A. in it. Greg Tate told me, “Ah, man! You nailed the L.A. thing!” I don’t know that I did. I think a fair argument against this book somehow could be that there isn’t enough. I mean they’re all there! Billy’s there, Horace is there, Easy E’s there, [Ice] Cube and [Dr.] Dre are there… They’re all there! It was hard. And that was the thing for me, to try and present it in a fair and balanced way, to try and understand that in their own small way, the Fellowship was very important. We would have no Bone, Thugs, ‘n Harmony, we wouldn’t have that same song style that Snoop has without people like that, you know? And to be able to put that back into the story in a kind of meaningful way, to me, was really important. Culturally, for the people of my generation, that’s an important part of the story that I’m happy to be able to at least allude to, you know?

Yeah! Can you also talk a bit about the moment of photographing for you? How do you approach and engage with the people you’re photographing and working with, and what about this process have you found to be consistent throughout your work?

Okay. So to me the trick is somehow to understand that it’s a moment of exchange, basically. That somehow someone is granting you the opportunity to make a representation of them, and that somehow your practice, whatever that entails—whether it involves a bunch of lights, or telling people what to do, or not telling people what to do, just stealing something, or hanging in the background and catching it—whatever that entails, we’re both involved in the production of this moment. I don’t know, there’s this thing where people point things out to you about your photographs: They seem stoic, they seem quite alone, they seem very serious… To me— I’m not a psychologist; I’m not the kind of person that’s reading into it, like, “Bill Withers, he’s this kind of guy! Therefore…” You know? And there are photographers who do that, but to me it’s much more about finding something that adequately represents that moment of exchange. I have people say to me, “You really revealed me.” But to me, I don’t know, I think I revealed the moment we shared. That’s all I did. Obviously there all kinds of formal things that come into that as well, like the performance, the framing, the fucking kind of film, the kind of lens… All that sort of stuff is part of it, but I keep that stuff fairly simple. I mean, I know my technicals, but I’m not a technical photographer by any stretch. And Mochila’s kind of the opposite; we’re much more invested in the moment of exchange than we are in the production itself. I don’t know if that’s useful, but…

Yeah! I don’t know, I do feel there’s always something very direct about your work, and that’s what that approach captures.

I mean, when people say things like direct, honest, revelatory, or whatever… That’s flattering, but yeah… I just go and try to present myself in as honest a way as I can and just try to see what happens. And let it happen. Don’t be scared to. You know what used to fuck me up? So much when I was younger, as a photographer, I’d have over-thought it. You know, “And this is what I want! I want the kind of image that we need to see of whoever it is.” I just reached a moment where I realized absolutely that’s what’s killing me. I’m going to be continuously frustrated and annoyed, and that’s not even what it’s about.

So one story that comes up in the book involves Madlib and the historical context of the cumbia rhythm. Is there another instance of things coalescing in this way, or a story regarding something surprising you’ve learned that you can share with us?

Wow, there’s fucking loads. [Laughter] Let me see… You know, one that I didn’t have a chance to really talk too much about that I would have like to have is in the northeast of Brazil. We went to Brazil to film Brazilintime as part of the Redbull Music Academy thing, and while we were there digging—and you have to imagine, I’m an Irish guy who grew up in a household where it wouldn’t be that weird to turn on the TV and there’d be accordion music. To me, as a young fellow who listened to punk rock and then hip-hop, I was just like that is absolutely not what I’m fucking interested in at all. [Laughter] But anyways, so I go to Brazil and I start to find this music from the northeast of Brazil, a lot of which has accordions in it, and I start to like it. Weirdly enough I have to go 6,000 miles to find that I like accordions! But in the process of thinking about music from the northeast of Brazil, I found there’s a music from there called “embolada,” or sometimes they call it “coco.” What that is, is a type of battle singing that was brought to Brazil, as far as we know, from Lisbon in the mid-1500’s. It happens in rhyme and it’s improvised, and when I rhyme you play the rhythm on a tambourine, and when you rhyme I play the rhythm for you; and we battle each other in that way. If you can imagine, as someone coming from a background that was interested in the notion of freestyling and battling and those kinds of competitive rhyming that existed in Los Angeles in the early ‘90’s, this was kind of an extraordinary discovery. And it really changed in many respects the way I think about hip-hop.

You know, there were a number of things that we found in Brazil that changed the way I think about hip-hop. And Colombia for me was really to think about the relationship to Africa. My understanding of the Americas’ relationship to Africa changed radically, especially in Barranquilla. Barranquilla is the missing link really. I think if you want to understand the Caribbean, you have to go to Barranquilla. It is a diggers paradise; you know they have a direct relationship to West Africa. But Brazil… First and foremost, if you really read the story of the beginning of samba, it’s really not that different than the beginning of hip-hop. There are many many parallels in terms of the displacement of a rural population moved into an urban environment, coming from a multiplicity of diasporic backgrounds with their musics, and how those musics begin to fuse together. This is very similar to the story of hip-hop. Then if you look at “coco” and “embolada,” the technology of hip-hop, if you will, the actual machinery kind of already existed, you know? That’s really what ’72 and Sedgwick projects with [DJ Kool] Herc and later with [Africa] Bam[baata] and [Grandmaster] Flash and everybody was about, a kind of naming that would allow the possibility of these technologies to be understood in a new way. And for me that was huge. It liberated, somehow, hip-hop from being a national project, which I believe in many ways it has become. But in fact it opens up the possibility of hip-hop as an international or global phenomenon, driven by diasporic concerns, driven by a post-Civil Rights politics, but with a scale and a reach that potentially goes far beyond. And this has happened. These are the kinds of things that when I was writing It’s Not About A Salary… didn’t exist yet, and they have happened. So eventually I started making a film about music from the northeast of Brazil and went there, and then I came to realize that some of the greatest practitioners of “embolada” were women, elderly women who just had fire and could absolutely destroy you. You know, seeing an 80-year-old woman spit tough lyrics, improvised… There’s really something special about that shit.

Yeah, I mean there are many many things like this: The first cover version of Fela Kuti happened in Barranquilla, Colombia. The first bootleg of Mulatu Astatke happened in Cali, Colombia. And we’re talking like in the ‘70’s. This is way before people were even tripping on Éthiopiques or tripping on Fela, first time, second time, third time around. And Fela had come to live in L.A. and had learned a huge lesson in L.A.. Took us a long time to figure out Fela, whereas in Colombia they figured that shit out immediately; that’s Carnival music to them. So there are a lot of those kinds of subtexts or subplots that have been pointed out over the years, or that I’ve helped find out about over the years, or that people like Madlib have pointed out to me over. I mean, that Madlib one to me is… The thing that’s so interesting about it is that it’s inexplicable. That’s not like some academic research there, that’s Madlib just having… The diaspora is alive in him, you know? It really is. [Laughter] As it is in many folks, but in him it’s particularly alive, so it’s wonderful.

To touch upon the [photos of] record keepers, who are referred to “keepers of culture” in your book, can you tell us a bit about some of these places and people that you remember most, or some of the records you found there?

Yeah! Let’s see… The first one that comes into my head is the guy at the very end of the story in terms of the collection of the images: It was going to Belém and going day in, day out to this place where there were a bunch of fellas selling used records, but it was really picked over, like there wasn’t much there. Then one day, after suffering from bad Portuguese, and you’re in the fucking Amazon so nobody speaks English, and kind of knowing that there were records there but just not being able to put my hands on them, then one day this guy just followed us out of the place, took us aside and said, “There’s a guy that lives down the back here that really has records.” So we were like, “Dude, let’s go!” So we go down there, and—it’s in the book—there’s a pink wall behind him, he’s standing there with a stack of records, his shirt is off, he’s like five-foot-zero, and his house was completely full of records. We had to go in through the front door, which was literally all of four-feet so we had to bend down, go inside the door, and then once you get inside there’s this front room where there are no records, but the whole house is full of records besides this room. Then you have to tell him artists. You have to tell him artists because basically he’s trying to see, “Well just how fucking deep are you? Because I’m not trying to really show you. I’m not really trying to pull out the winners unless you have some idea of what you’re getting yourself into.” So it was me and Quantic… Yeah, man, it was one of the funnest. We went back there twice afterwards. After the first day when we went back, we were like, “Holy shit! We made an impact on this man’s life” because the whole house has been cleaned up, he was actually wearing different clothes… But the dude was a proper head. And to me, that’s really when it’s at its most exciting. When you go to visit somebody that, you know, Carlinhos in Discos Seite in São Paulo is that kind of a guy, Kamau Daáood, who doesn’t really deal records as much anymore in L.A., but he was that kind of guy. The kind of guy like, “Oh, that’s what you’re interested in? You know, you might want to check this out because…” But I mean, I find ways to connect with all kinds of people, and there are people in this book that just sell records because that’s how they make money, for whatever reason. But the ones that really stand out are generally the ones that have a real connection to the music and that are curious as to what motivates other people to find their way to the kinds of records that, you know, the difficult ones, the ones that not everybody has. Especially when they recognize that you’re there for the music, you’re not there because you’re trying to turn up a rare record because you know you can resell it and make money, but they actually acknowledge you’re there for the music. They’ll order in a beer, they’ll pull out some of their own stash and start playing you a few things that they like, that they think you should pay attention to… This is always the super win, and that’s the kind of knowledge that, you know, there’s no price on that shit; that’s the you just gotta go there stuff. And to me, that’s the primary research aspect of this kind of work. ‘Cause yeah, I’ve had the benefit of standing in the room with fellas that, like, only collect salsa records in Cali and have been collecting salsa records for forty years and are fucking maniacs. They can tell you anything, you know? So it’s very exciting to be able to do that kind of thing. I think my phone’s going to die, let me see… Oh yeah, I’m getting there.

Oh no! Then a couple final questions really quick, I wanted to ask how you feel your relationship with music has changed over the years?

I would say it’s deepened primarily, you know? I don’t have as much time to, sort of, listen in a leisurely way as I used to. I have a child now, a lot of fucking job stuff. But nothing makes me—anyone who knows me knows, if you wanna mellow me out, man, just bring me to a good record store and let me at it. Nothing will make me happier than an hour of random digging. It’s just the best thing ever to me, you know?

And finally, how do you go about approaching a DJ set? And what are you currently listening to?

DJ set is very much trying to understand, like, what will work in this situation? And my favorite kinds of DJ sets are the kinds of ones where I don’t play a single record that anybody knows. That’s, like, the fantasy. Everyone’s hyped, but no one knows any of the music.

And what am I currently listening to… That’s a very fucking good question. Lately I came upon some Sun Ra shit, some kind of rare Sun Ra shit; I’ve been listening to that. I’ve been listening to Phineas Newborn. [Laughter] I’ve been listening to…. What else have I been listening to lately, man? Spacin’ out right now. Well. Okay. Truth be known, J-Rocc made a mix inspired by the book, and I have to be honest, since the last week and change that I got it, I’ve been listening to it. I cried the first time I heard it, man. ‘Cause I mean, I love J-Rocc, man; he’s the fucking Don of Don’s to me as far as DJ’s. Then to hear him go into his crates inspired by who’s in the book, from all the random ones you wouldn’t even think of to, you know what I’m saying, like Saafir… Ah, man! It’s a nice mix. So yeah, that’s what I’ve been listening to actually. [Laughter] Truth be known…