Mysterious tales from the rural: Dan Attoe

Painter, sculpter, nature lover, biker and bullfighter… Yes, we are talking about one man: Dan Attoe. We were instant fans when we came across his work and finally got the chance for a chat. We talked about the rural and the city, being on the move and growing roots, families and, of course, beavers.

Interview byYetkin Nural

Originally published in Bant Mag. No:24, November 2013 issue.

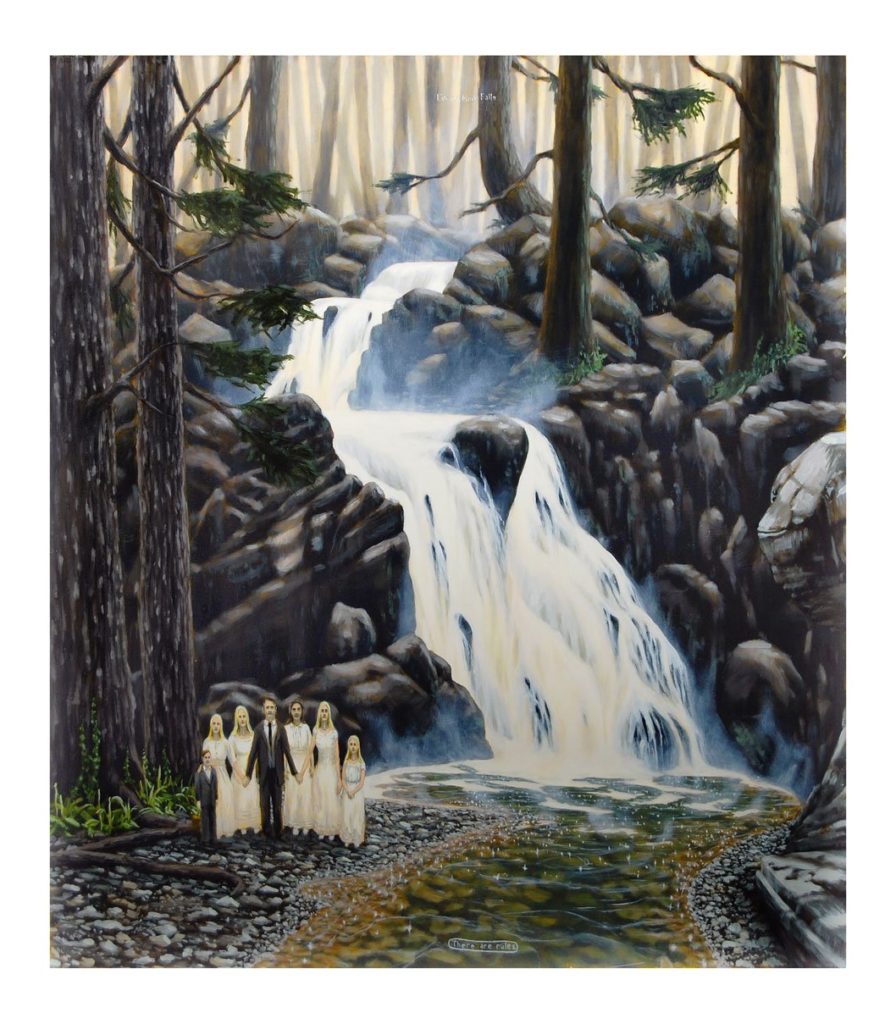

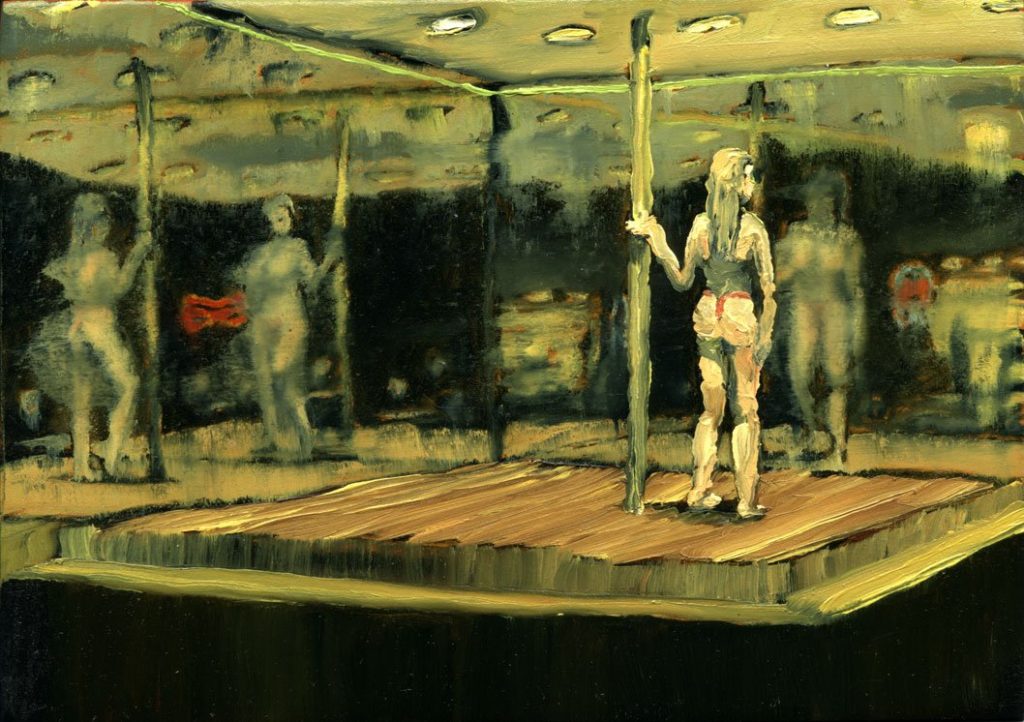

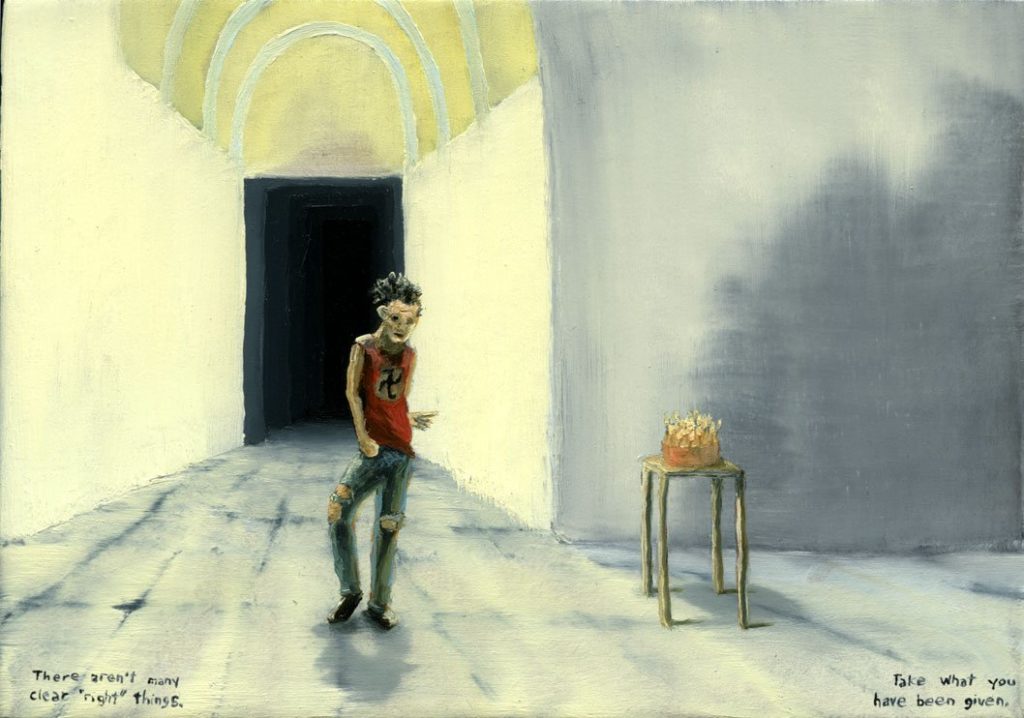

Dan Attoe listens to the water running through the valley, the beaver family at the docks, the mountains and deep forests; filtering them through his mind’s eye and produce dreamlike images that teases the viewer with intriguing stories hinted in his paintings. Sometimes texts or drawings that don’t make it into the paintings end up finding life in a neon sculpture or some other form. Not much goes to waste with Attoe’s creative energy that buzzes in everything he does.

I have read that you have a specific way of working. A sort of schedule, a day starting with meditation and followed with drawings, some of which evolves into a painting. Am I right? Do you still work this way?

Yes, I have a pretty specific process, but the actual schedule of it is pretty flexible. I don’t have a specific time that I start in the day, but I do draw a new image every weekday that I arrive at through daily meditation. Some of these drawings become paintings, and there’s usually text and cartoonish drawings alongside the daily images that occasionally make it into the paintings, or get turned into neon sculptures.

How did you come up with this system and how do you think it helps with your work?

I came up with this through a combination of psychological research models and a writer’s journal in addition to Zen Buddhism. I initially started making a painting a day as a way to monitor my own psychological development after quitting my major in psychology in 1996. This process helps me to find subject matter that interests me. This is always changing and growing with me and my interests. At this point, I’ve found a framework of a visual vocabulary that I gravitate toward, and the changes happen in nuanced ways within that. The daily image making allows me to make images that are further afield from what’s become known as my territory, and find new things to bring back, or new directions to explore.

Can you tell us a bit about your working environment and what is going on in your studio?

I have a studio in a retail space in a small town in Southwest Washington state. It’s right on the Columbia river, and I can walk over there from my door in about two minutes. There are some docks in the river across from me, and a family of beavers that patrol there at night, and I go and check up on them almost nightly. Inside my studio, I have a series of paintings that are landscapes with water in them – lakes, oceans, rivers and waterfalls, usually with little figures in there too. I also have all of my woodworking stuff – I build my own frames and sometimes crates to ship my work in.

You have lived in a number of different places throughout your life – from Washington to Idaho, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa. How do you think this nomadic way of growing up affected you and your work?

My father worked for the U.S. government when I grew up, so we moved around when he was re-stationed. We were also always near some kind of body of water – the Puget Sound/Pacific Ocean, several different rivers in Idaho and Lake Superior in Minnesota – this is all directly affecting my current work. Also, this way of growing up has given me interesting perspective – I was always around long enough to get to know everyone in the small towns or remote communities that I lived in, but was never quite a long-time local. I have two different towns that I primarily grew up in – Ashton, Idaho, and Silver Bay, Minnesota – both of them are equally hometowns to me. My parents live in Merrill, Wisconsin now, and the place they live feels like home as well, but I didn’t grow up there.

All of this gave me an inside comfort with the local culture and I’ve spent enough time in each of these places to have long-time friends there, but I’ve always been aware that another life could be lived as easily somewhere else, which keeps me from ever feeling completely “settled”. I think it allows me to see certain aspects of culture with a perspective that someone who has grown up knowing them all their lives wouldn’t have.

You are living in a rural area close to Oregon with your family for some time now. You think you are finally growing roots and settling down to a place? Is there a longing for packing up, moving and exploring new territories?

There is always that longing. However, I do feel the need to dig in and finally have some kind of a home base. The town that I’m in now (Washougal, Washington) is tied for the longest I’ve lived anywhere with Ashton/Island Park, Idaho at 7 years. Idaho and Washington are both states I’ve lived in for ten years. Minnesota is close behind at 8. I’d like to settle in somewhere for long enough that my daughter has a place to grow up.

I’m a little baffled by cities. I think I just don’t quite know how to cope there. In writing about Sherwood Anderson, Upton Sinclair once said something like: “The city man thinks of other people, and the rural man thinks about the universe.”

Talking about family and settling down; what kind of an effect did being a father and a husband have on your work?

Oh, there are a few things that it did. I think taking on the responsibility of marrying someone made the importance of my work more intense, and it also challenged me to change my routines and thinking. Having a child is a further exercise in emapathy than marriage, but similar in scope. It’s also forced me to reflect on my life, and on the vulnerability of others and my affect on them in ways I never had before. Both of these things have made me take my work more seriously, and they’ve also broadened my subject matter in nuanced ways. I think the female figures in my painting have grown in their depth and roles. I also think that my interest has been honed in a bit more.

Both in your life and your work, you have been somehow avoiding the “urban”. What do you think about cities and urban life?

I do occasionally make a painting in an “urban” setting, or an interior that could be in a city. However, my imagination doesn’t often wander there. The images I see when I meditate are unrestricted – just following my nose for twenty minutes. For whatever reason, I find my mind drifting to images of rural landscapes, forests and lakes, rivers and streams. I don’t know if it’s because I imprinted on that growing up, or because my mind just finds more comfort there.

I’m a little baffled by cities. I think I just don’t quite know how to cope there. In writing about Sherwood Anderson, Upton Sinclair once said something like: “The city man thinks of other people, and the rural man thinks about the universe.” I just think that our minds get programmed early to play certain games to keep us interested in our environment. I lived in New York last summer, and was completely lost there for about a month. I gradually got comfortable, and started feeling like I could navigate the city and its people, but it took me some time, and I did feel out of touch with my more usual way of thinking. I’ve lived in Minneapolis, Portland and Iowa City before too (the last one isn’t quite what you’d call “urban”), and I always enjoy certain aspects of my life in these places, but I find living outside of cities to be far more rewarding.

What is it about the rural setting that you draw your inspirations from?

One big thing about rural life that is important to me is space. I can see farther, and the space that I see has less interruptions from man-made objects. I also have a natural drive to explore, and I don’t feel as excited to explore in cities. I like to be able to drive wherever I want to go, which is harder to do in cities. There’s just a relaxation that comes over me when I see more space and less people and buildings.

Originally, this group [Paintallica] was founded as a way for a me and a group of friends to continue a dialogue of criticizing one another’s work and thinking. We intentionally wanted to hurt each others’ feelings, and in doing so, hoped to get honest criticism about our work.

There is certainly a story telling type of quality about your work. There are historical or literal references, even texts that help shape the fiction that is being conveyed in your paintings. What kind of stories interest you, or what kind of stories are you intrested to tell with your work?

I like all kinds of stories! I love early American stories, and history – both from Native cultures and settlers. I like desperate tales of rural life – Flannery O’Conner, Cormac McCarthy and Sherwood Anderson all come to mind. I often think of my work as fiction, but I think I’m gravitating more toward less literal stories. I just paint moments of time that happen in a place, and there’s often a suggestion of a sequence of events, but what that is is not always clear. In the past, I sometimes wanted those things to be more clear, and I’d write stories on the back of my paintings explaining things. Now, I just want things to describe a moment with the suggestion of something more.

You are also a founding member of the artists collaboration group, “Paintallica“, which creates a body of work largely based on installations. It comes across as something like a camping and hunting trip between a group of friends took an artistic turn somewhere. What kind of an idea formed this group?

Originally, this group was founded as a way for a me and a group of friends to continue a dialogue of criticizing one another’s work and thinking. We intentionally wanted to hurt each others’ feelings, and in doing so, hoped to get honest criticism about our work. Eventually, it turned into all night painting, drawing and building parties where we’d each make something and let the others contribute to it. Now, I think it’s about maintaining that same honest energy that fuels making a wide range of things – keeping each other from thinking too hard about something to the point that we don’t feel that primal excitement about it. It’s become an investigation into why making visual objects is a fundamental human activity.

What kind of an experience is it to work within a colloboration compared to working solo?

The two practices are very different, but there are things that I bring from each of them to the other. My own work is very meditative and slow and deliberate, but in order for me to put all of the work into it, I have to maintain that fundamental interest in the content – getting rough and honest interaction from the folks in Paintallica has helped me to bring that to my own practice – I can tell when I’m trying to fool myself. At least, when I’m working on my own paintings, I don’t have to worry that I may get a beer can thrown at my head at any moment.

What have you been working on lately?

I’m primarily working on paintings for my upcoming solo show at Peres Projects in Berlin in March. Those will be the landscapes with water. Paintallica had a show out here in Portland at ROCKSBOX that came down last month, and that was a series of chainsaw carved cedar logs and drawings and paintings. I’m also spending a lot of time with my daughter too.

What kind of music are you listening to lately? Any new bands that you are hooked on these days?

I’ve been listening to Grinderman’s remix album heavily for the last year, also Murder by Death, Giant Sand, Menomena and Crooked Fingers. I listen to a lot of mellow country and folk too – Josh Ritter, Neko Case, Roger Alan Wade (Johnny Knoxville’s cousin), Slaid Cleaves, Todd Snider and Gillian Welch.

Finally any favorite upcoming artists we should watch out for?

Kevin Earl Taylor, Ralph Pugay, John Kleckner, Brent Wadden, Wes Lang, Lori Gilbert, Will Bruno, Jay Schmidt, Jesse Albrecht, Jamie Boling, and all the guys and gals from Paintallica (who you can find on our website)!