Loren Munk's Logistics of Art

For the last three decades, Loren Munk has been what one might call a fixture of the art scene in New York City. Starting off working as a delivery man of art supplies for an art store, he has been exploring, rewieving, critiquing and creating art since then.

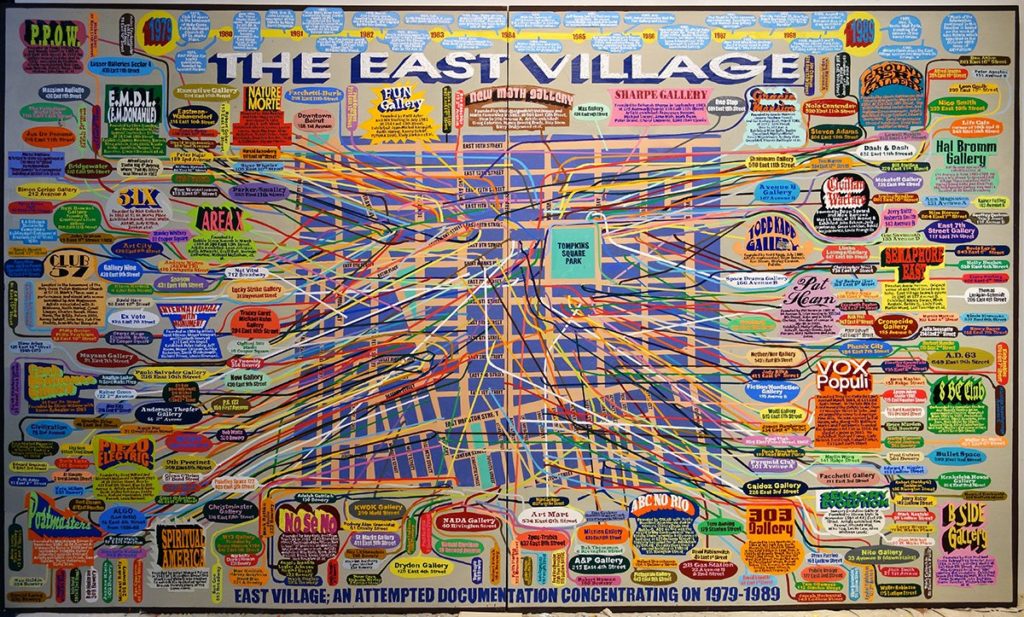

At around the halfway of his New York City life, Munk came up with an idea which allows him to employ his accumulated knowledge of town’s art scene and translate it into his own paintings: creating maps and diagrams of the city’s art history. It sure is a challenging task, one that Munk handles with skill: despite the density of the data at hand, Munk’s map paintings gives great joy for a slight look, and promises much more for a longer inspection.

*Originally posted in Bant Mag.’s May 2014 issue.

Interview by Yetkin Nural

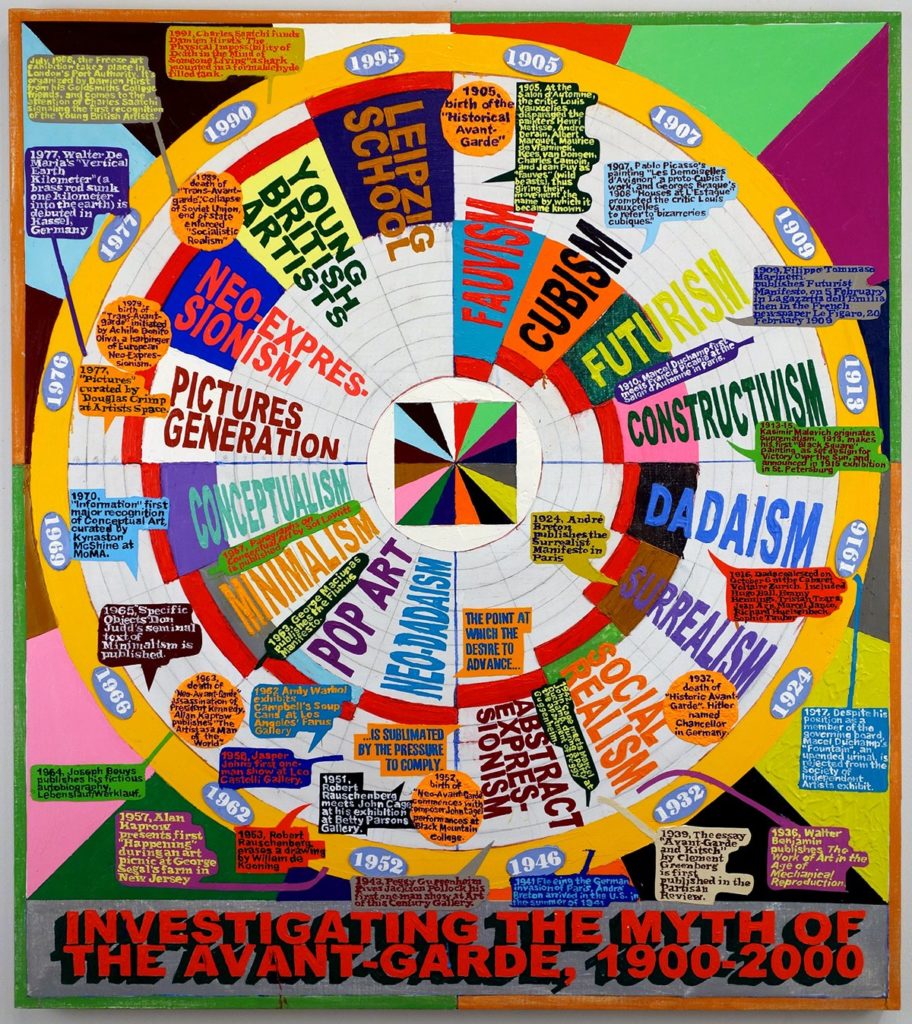

“Investigating the Myth of the Avant-Garde 1900-200” (2013-14), oil on linen, 54 x 48 inches (Courtesy of Freight + Volume)

“Untitled (Gorky Portrait)” (2006-2007), oil on linen, 48 x 42 inches

You have been mapping the art scene of New York City in your paintings. I am curious about the process: how do you decide on a topic, how do you collect the information and what kind of artistic choices are in question when you start applying the data on the canvas?

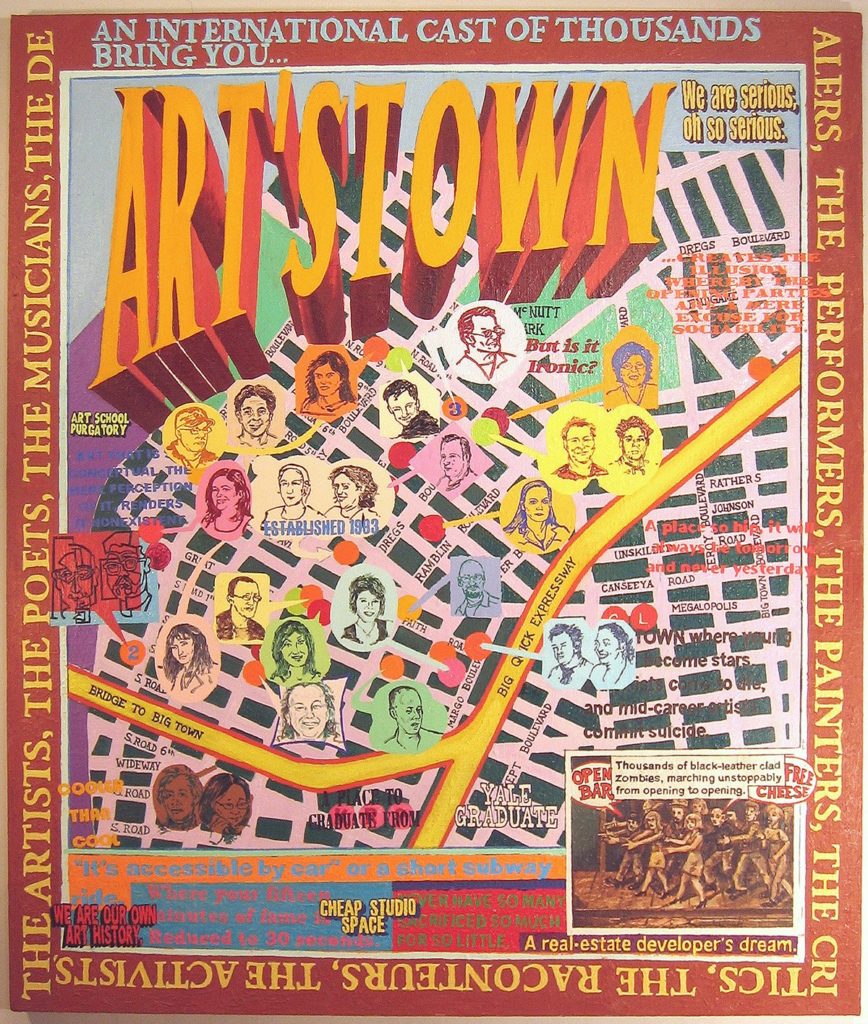

When I began this project, about fifteen years ago, my main subject was Brooklyn, specifically the Williamsburg neighborhood. I was one of the few local art reviewers to cover what was happening in that burgeoning art scene. I wanted to carry my interest in the community over from the writing and reviewing into my painting. One solution I came to was the creation of maps to chart its course of evolution. As I finished one map I realized that there were other neighborhoods that had influenced the development of the Williamsburg area, so I started a map of the East Village, another scene I’d grown up with and knew intimately. It all seems like the subjects chose me rather than me consciously making the decisions.

The information has been collected over many years. One of my first jobs when I moved to New York was driving the delivery truck for an art supply store named Utrecht. I’d deliver paint, canvas, stretchers and such to artists, again mostly in the East Village, or SoHo. I wrote down the names and addresses of artists that I made regular deliveries to in little notebooks. I kept those books for twenty years. (I still have them.) When I started the maps, those old notes were the foundation of the database, As the database grew I sought out published listings or directories that contained more historic names of artists and galleries. I’d spend afternoons in the rare book section of the New York central library collecting lists of names from long out of print directories. I asked friends, looked in old phone books, magazines and now I use the internet. Whenever I’d come across an address in my historic reading, I’d copy it down in the little notebooks. Anything to help grow the database.

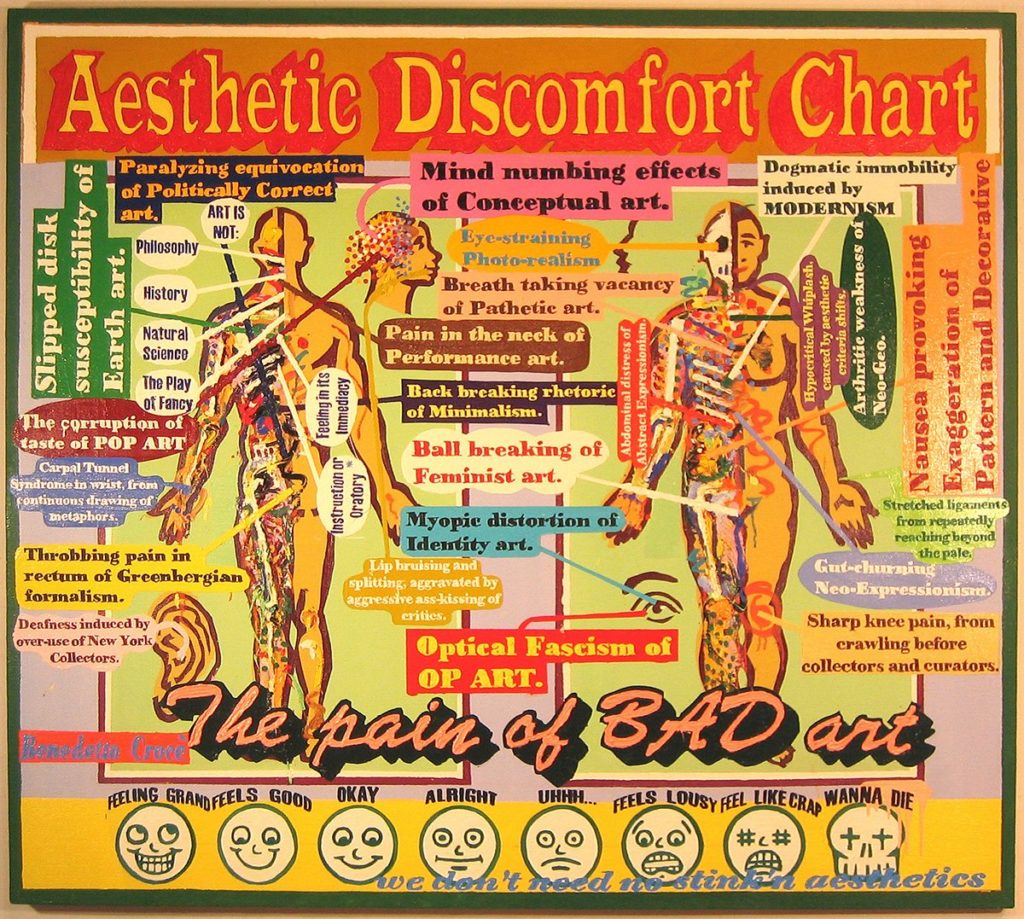

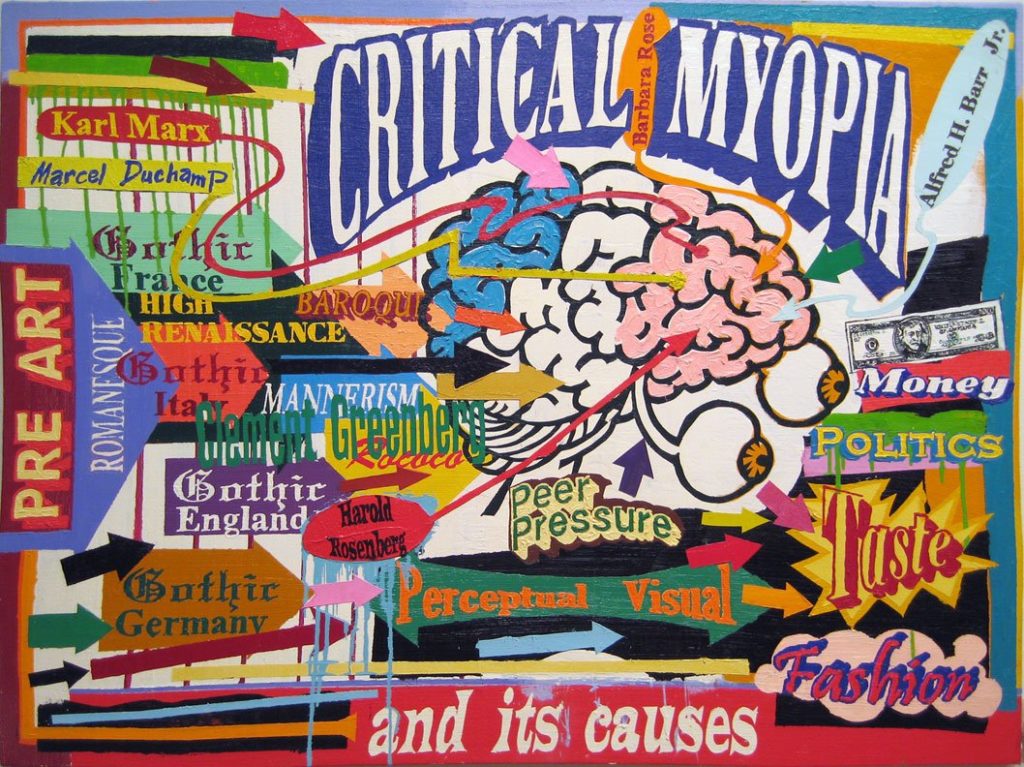

Basically, I have two intertwined subjects, one is the maps, and the other is related more to flow charts or graphs. As a longtime painter with a design background, I’m always trying to use compositions that will attract attention through color, line or shape. The maps are more straight forward. The charts present another challenge, because there is a certain amount of “theory” combined with the data, I like to use things like visual humor or satire to help make the point. Sometimes the work borrows compositions or parts of compositions from other art works, or things I see around me, like advertisements, posters or comics. but always with a painters eye for color and composition.

Can you tell us a bit of the technical aspect of your work? Do you always choose a certain format and medium, do you experiment with different materials or consider various forms of visual language?

I always considered myself first and foremost an oil painter, carrying on the grand legacy of the New York School and painters like Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns. Because of it’s long history as the ultimate art form, it’s been said that oil painting on canvas is the most conservative, and reactionary of all the art mediums. Perhaps one of its conceptual attractions is the desire to rehabilitate this medium by using it to designate and present its own history.

I also do a lot of work on paper as studies for layouts or noting ideas. I like to play around with collage, watercolor, color pencil and anything else I can stick down.

As for visual language, the most basic answer to that would be my use and interest in text and typeface. One of the most intriguing recent trends I’ve witnessed is the increased use of writing in painting. Some of this might be a result of conceptual art, or perhaps the influence of “Post-Modernism”, the Deconstructionists, for whom, the mind can preserve reality only through “text”. I’m fascinated with various type designs, their shape and form, how they evoke emotional responses and memories just like color or composition.

Photography has become more interesting, and I take lots of pictures that I use as reference for the paintings and posting on line, but I haven’t gotten into developing them into a larger separate body of work.

“Aesthetic Discomfort Chart” (2005-6),oil on linen, 54 x 60 inches, (Courtesy of Freight + Volume)

“Art’stown” (2000-2005),oil on linen, 68 x 58 inches (Courtesy of Freight + Volume)

You have been mapping the art scene of New York City in your paintings. I am curious about the process: how do you decide on a topic, how do you collect the information and what kind of artistic choices are in question when you start applying the data on the canvas?

When I began this project, about fifteen years ago, my main subject was Brooklyn, specifically the Williamsburg neighborhood. I was one of the few local art reviewers to cover what was happening in that burgeoning art scene. I wanted to carry my interest in the community over from the writing and reviewing into my painting. One solution I came to was the creation of maps to chart its course of evolution. As I finished one map I realized that there were other neighborhoods that had influenced the development of the Williamsburg area, so I started a map of the East Village, another scene I’d grown up with and knew intimately. It all seems like the subjects chose me rather than me consciously making the decisions.

The information has been collected over many years. One of my first jobs when I moved to New York was driving the delivery truck for an art supply store named Utrecht. I’d deliver paint, canvas, stretchers and such to artists, again mostly in the East Village, or SoHo. I wrote down the names and addresses of artists that I made regular deliveries to in little notebooks. I kept those books for twenty years. (I still have them.) When I started the maps, those old notes were the foundation of the database, As the database grew I sought out published listings or directories that contained more historic names of artists and galleries. I’d spend afternoons in the rare book section of the New York central library collecting lists of names from long out of print directories. I asked friends, looked in old phone books, magazines and now I use the internet. Whenever I’d come across an address in my historic reading, I’d copy it down in the little notebooks. Anything to help grow the database.

Basically, I have two intertwined subjects, one is the maps, and the other is related more to flow charts or graphs. As a longtime painter with a design background, I’m always trying to use compositions that will attract attention through color, line or shape. The maps are more straight forward. The charts present another challenge, because there is a certain amount of “theory” combined with the data, I like to use things like visual humor or satire to help make the point. Sometimes the work borrows compositions or parts of compositions from other art works, or things I see around me, like advertisements, posters or comics. but always with a painters eye for color and composition.

Can you tell us a bit of the technical aspect of your work? Do you always choose a certain format and medium, do you experiment with different materials or consider various forms of visual language?

I always considered myself first and foremost an oil painter, carrying on the grand legacy of the New York School and painters like Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns. Because of it’s long history as the ultimate art form, it’s been said that oil painting on canvas is the most conservative, and reactionary of all the art mediums. Perhaps one of its conceptual attractions is the desire to rehabilitate this medium by using it to designate and present its own history.

I also do a lot of work on paper as studies for layouts or noting ideas. I like to play around with collage, watercolor, color pencil and anything else I can stick down.

As for visual language, the most basic answer to that would be my use and interest in text and typeface. One of the most intriguing recent trends I’ve witnessed is the increased use of writing in painting. Some of this might be a result of conceptual art, or perhaps the influence of “Post-Modernism”, the Deconstructionists, for whom, the mind can preserve reality only through “text”. I’m fascinated with various type designs, their shape and form, how they evoke emotional responses and memories just like color or composition.

Photography has become more interesting, and I take lots of pictures that I use as reference for the paintings and posting on line, but I haven’t gotten into developing them into a larger separate body of work.

Do you ever consider exploring and creating maps of other sorts of info? Like something outside of New York? Or outside of art?

The information seems to lead where it leads. I’m just finishing a large map of California featuring both the Los Angeles and San Francisco communities. I realized that a lot of what has happened in New York had its beginnings in California. Now, I’m thinking I’ll have to do large individual pieces for each town.

Recently I’ve been reading a lot of the opaque art theory from the 1980s, Guy Debord, and the Frankfurt School theorists associated with October Journal. That has interested me in the whole notion of aesthetics, Marxist philosophy and cultural politics. Though these subjects are tightly twined with art, they’ve given me different and interesting new ideas to play with for paintings.

“The Dualistic Nature of Aesthetics” (2007-2008), oil on linen, 36 x 48 inches

“Critical Myopia and its Causes” (2006-2007), oil on linen, 36 x 48 inches

Creating maps of information as an art form is relatively common format and there are a lot of unique styles that artists come up with. Are there any artists that inspire you in this particular art form?

I’m a big fan of the sixteenth century English mystic Robert Fludd. He designed some of the most beautiful engravings of all time in his quest to explain his metaphysics. Using abstract shapes and line, he illustrated concepts of heaven, the spirit, and man’s soul, and he did all this two hundred years before Kandinsky or Piet Mondrian.

Francis Picabia during his proto-Dada phase made many paintings and drawings that combine a “machine aesthetic” with diagrammatic content, often using text with the names of his friends and collaborators. I appreciate his inquisitiveness, technical skill and experimental willfulness.

Stuart Davis was the greatest of the New York Cubists. I love his use of brilliant punchy color, hard edged shapes and jazzy use of text. His quotidian subject matter and references to advertising influenced me and a generation of Pop artists.

Another great inspiration closer in time is Alfred Jensen. Jensen was a member of the New York School and a friend of the Ab-Exers, but he always had a more rational and systematic approach to his work. He would base compositions on things like the Mayan calendar, the I Ching, or the Pythagorean Theorem. Many of the painting look like checker boards using bold, pure, chunky pigment.

You also shoot video documentaries / commentaries of New York art scene, exhibitions and behind the scenes. And you do this under the name James Kalm. First obvious question is, why the pseudonym? Is there a story?

As a longtime denizen of the New York art scene I’ve seen how careers are made and unmade. Despite their claim, that creative communities are tolerant and liberal, the truth is, there are sins that can not be forgiven. Chief among these is being an artist that has failed or gone out of fashion.

Having had an initial success during the onslaught of Neo-Expressionism. I was one of a few artists who’d developed “Kitsch Art”, a further perversion of “Bad Painting”. In the mid 1980s, when Neo-Geo and Neo-Conceptual Art made their appearance, anyone who wasn’t on board was instantly obsolete, disparaged, and pushed to the sidelines. The art market collapsed later in the decade, and the AIDS epidemic wiped out a generation of young artists. The East Village scene evaporated over night. My wife Kate and I had started a family, and I was working with private dealers is Europe. The next ten years were happily spent nesting and raising kids in Brooklyn.

Due to our chosen isolation, by the late 90s whatever presence, sales or reputation I’d achieved had all vanished. Kate said “You don’t exist in the New York art world anymore”, and she was right. After years of schlepping around portfolios and books of slides, searching for some place to show, no reputable gallery would even consider giving me an exhibition, and few American collectors or critics were interested in the work. As a means of reengaging with the art world I decided to take up art writing and criticism. But I didn’t want to be known as a failed painter who was now writing reviews. James is my middle name and Kalm is an anagram using the first letters of Kate’s and my names. I invented James Kalm and I kept this writer identity secret for nearly ten years. This anonymity was a valuable tool. In one way I considered it a long running performance piece. It allowed me entry back into the real art world, the back rooms of galleries and studios, not as a desperate artist looking for help or a show, but as an interested observer and commentator. Another unexpected benefit was it forced me to reconsider the value of art criticism, and educate myself in its history, philosophy and theory. It brought me into contact with the local art critical community, so that I could recognize who is who, and get to know them and their writing personally. I started contributing to the Brooklyn Rail around 2000 and have probably spent more time writing about the Brooklyn scene that anyone in New York.

Again, when you look back the three decades that you have spent in NYC and let yourself to be nostalgic this time, what do you miss and what do you think is being lost in the art scene?

Twenty-five years later, I still have trouble realizing just how devastating the AIDS plague was. I just spent two years working on a large East Village map. As I amassed my list of artists, galleries and addresses, I was struck by how many of the kids I’d known personally had died due to the AIDS tragedy.

Another change is the art market itself, the art fairs, mega-galleries, online sales, and how many people are obsessed with money and the apparent “inequality” of its distribution. Although the there’s always been an imbalance in outcome, artists as entrepreneurs always seemed to realize that was part of the game. It seems to me that proportionally, values and prices for art were nearly as high during any of the various market bubbles we’ve experienced over the last thirty some years. Although the scale has increased, none of this is new (just read some history). What is new is how many young artists gladly relinquish their creative freedom and autonomy to become slaves to their perceived status as “victims” of the market.

Along with this notion is the continued bifurcation of the creative community, not so much along the lines of the haves and have-nots, but into the successful and recognized versus the unsuccessful and unrecognized.

A perpetual problem facing artists is the lack of cheap living and studio space. With the massive number of new untested artists being pumped out of universities and academies every year, neighborhoods where artist have found congenial situations are being stressed as never before by real estate pressures. Partially due to their own success, these artist’s neighborhoods attract developers and young urban professionals who want to live in trendy areas. One consequence of doing the map pieces is the recording of how these neighborhoods change and evolve. This has been happening in New York since the nineteenth century, and I’m hoping we can come up with creative solutions to the problem.

What have you been up to lately? Any upcoming shows or new projects that you would like to share?

I’ve just wrapped up a major show at Freight+Volume Gallery, in which I was able to present works from the last ten years. That came on the heels of another major group show there that I helped curate last summer titled “The Decline and Fall of the Art World Part I” which included works by Karen Finley, William Powhida, Jade Townsend, Alex Gingrow and Michael Scoggins.

Although in many ways I’m an anti-academic, I delivered a couple of talks one at Harvard University and another at Rutgers last month. I’ve also been providing critiques at the New York Studio School. Today I’ll be hosting a class of students From the School of Visual Arts here at my studio. Other than that the most exciting thing I can think of is going to work on huge new map paintings (SoHo and Bushwick) in the studio, and visiting more shows to record some video.

“Greater Williamsburg” (2005-08) oil on linen, 48 x 60 inches

“The East Village 1979-1989” (2011-2013), oil on linen, 84 x 145 inches (Courtesy of Freight+Volume)

And finally, can you share some of your latest discoveries in New York art scene, any upcoming artists that we should look out for?

There are lots of very creative folks out there so I will only mention a few.

It’s not just new artists who interest me but new methods of distributing cultural production. Art must always be receptive to new technologies and their effects on society. I’ve gained some recognition because eight years ago I saw the potential of the internet and YouTube and formulated a way to use it according to my creative needs. One of the people doing something like that now is the very funny performance artist, Hennessey Youngman (AKA Jayson Musson) https://www.youtube.com/user/HennesyYoungman

Because of the decline in hardcopy art criticism due to the rise of the internet, I’m also interested in people who have taken the initiative to figuring out ways to support art information and critique online. The site HYPERALLERGIC.COM published and edited by the partners Hrag Vartanian and Veken Gueyikian, does a great job of covering the scene, and keeping the pot boiling.

Over the past eleven years, I’ve also been one of the first art writers to record the evolution in the Bushwick creative enclave. A short list of artists how’ve caught my eye there would include: Andrew Ohanesian, a very ambitious installation artist whose projects have turned part of the English Kills gallery into a giant beverage cooler, and Pierogi Gallery’s Boiler into a slick tract house that’s trashed during it’s drunken opening party. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wmTltTTACss

Meg Hitchcock, an obsessive collage artist whose gallery filling installations have reconstructed pasted letters from the Koran into verses from the Bible and vice versa. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1CwxZ9ZAKI

Finally I also appreciate institutional critique and one of the most significant current practitioners of this mode of conceptual art is Jennifer Dalton. Much of her work deals with a feminist view of the art world and it inequities. She’s gone into partnership recently with Jennifer McCoy to open their own small gallery/project space Auxiliary in East Bushwick, where they present other artists working in sympathetic conceptual modes. http://www.auxiliaryprojects.com/

Thanks to you folks at Bant Magazine, and as always, Thank You Kate.

*Originally posted in Bant Mag.’s May 2014 issue.