World is a much more complicated place than merely a war ground between the good and the bad: Adam Curtis

We were introduced to BBC journalist/documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis through ATP (All Tomorrow’s Parties) London. He was in Istanbul for a week in February as a guest of !f Istanbul Independent Film Festival and we got together for an interview. Our conversation commenced with Curtis’ last movie “Bitter Lake”, stopped by the intersection points of politics, journalism, science, technology and music and ended up with the leftist movements recently on the rise in Europe and USA. In the documentaries he has been producing for BBC in the last 30 years, Curtis has been telling us the political and intellectual history of the 20th century from the lens of a camera soaked in acid rather than the “serious and boring” tones of mainstream journalism. Curtis has a loyal follower base due to the musical choices, forgotten TV recordings and trash pop aesthetic he puts into use in his movies, which can be found online by those who are curious. We also asked Curtis how he constructs his approach to movie making given that he complains about the scarcity of journalism pieces that both entertain the audience and also present them the fact that the world is a much more complicated place than merely a war ground between the good and the bad.

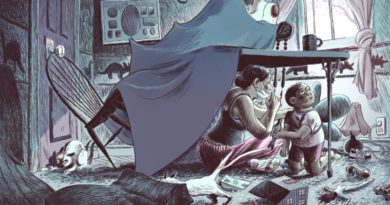

Interview by Mehmet Ekinci, 13melek – Photo by Aylin Güngör

In “Bitter Lake”, you pinpoint the meeting between King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud and Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945 as a crucial turning point. Then, you tell a historical narrative regarding how the current situation in Middle East could be traced back to that event and its ramifications on Afghanistan. What drew you to this topic?

I am not saying that everything in the Middle East goes back to that. I am saying that it is a very interesting starting point for looking at the currents of history that have led to our present confusion at Afghanistan. Britain has been fighting a war for 13 years in Afghanistan. Despite the bad reporting, it was obvious that the war is being lost and we completely misunderstood Afghanistan. As a journalist, I wanted to tell the story of why we went to Afghanistan and why it had gone disastrously wrong. In all the films that I have ever done, I have gone back and tried to look at the roots. What I have found is that when you do so and then come back through history to the present day, you look at it in a different way. It does not change everything but it changes your perspective. It puts it in proportion as well. One aspect is the war we have been fighting. The other is finance and money. I think what has happened to money in the modern world is so important about our confusion. The key thing is that somewhere in the early 1970s, two things happened: One is that the Saudis raised the price of oil as a political weapon. That unleashed this flood called “petrodollars” around the world. The other was just before that, President Nixon coming off the Gold Standard which means that he actually allowed the dollar to float freely. At this point, the idea of having a benchmark which you could judge something against disappeared. I thought that the meeting between Roosevelt and Ibn Saud was important because the roots of those two things meet there. One is, US implicitly begins protecting an intolerant and quite rootless version of Islam, Wahhabism, which I think plays a very important role in corrupting Islamism as a revolutionary force. This is a thing that most people don’t understand. The other is that the roots of that money flood go back there. Our confusion in 2008 is also about Afghanistan and about money. So, if I was going to tell the story, that is where I had to start.

A theme that runs through your work is that we live in a complex and chaotic world today and as politicians frame the world in simplistic dichotomies such as good vs. evil, one loses the essence of the truth. You touch upon this in “Power of Nightmares” too, in some other way. How does the war in Afghanistan fit into this picture?

When I made “Power of Nightmares”, I went back into the history of Islamism and discovered that what we were being told was very simplistic. September 11th was like a shock reaction and we had become frightened just like children. I begun to realize that things were far deeper than that. Politicians in the West, in Britain and America, have come to have a very simplified view of the world in the last 20 years. We divided the world into goodies and baddies. We said that, because we are strong, we should go and protect the good people against the bad people. “Bitter Lake” is trying to explain the roots of this. 40-50 years ago, the politicians and us had a much more sophisticated understanding of the world, and above all, power. We understood where power comes from. You, in this country, know about power. You feel it everyday. I am sure people talk about it. In my country, they don’t. In America, they don’t. They just talk about how they feel as individuals and things seem to have just happened. That’s because we have retreated from understanding power and we don’t really understand what happens.

The same is true for Afghanistan which was that you go to this country and you rescue the innocent people and get rid of the bad war lords and then everyone will be happy. I tried to show in “Bitter Lake” that when you do so, you find that things are far more complicated. In a place like Afghanistan where there has been a struggle for power since the revolution of 1979, no one is good and no one is completely bad except some psychopaths. Everyone is caught up in this complex process and we just cannot deal with it since we retreated into this totally simplified view. I know that it is very difficult to report on ISIS, but we treat them as evil demons rather than something quite complex which grew out of the conflict in Iraq in 2003. The point is not to justify them but we won’t report it. I do think that this is the malaise of the West. It is childish and lazy. But it is also understandable. In the face of a complex world, you retreat into your bedroom, look at your toys and say, “Here is bad and here is good”. You never look outside the window. That is fine in your bedroom but when you do it in a world that is terrible, that is what “Bitter Lake” is.

We know that you used terabytes of discarded footage by BBC to construct “Bitter Lake” and you say that the responsibility falls on the journalists to make this complexity understandable. Your movie in a sense shows that reality is left in the shades by just using sound bites through the journalistic process. We know that you define yourself as a journalist if anything else. What is your take on the current state of journalism?

You have to be nice to journalists. It is a very difficult job. Especially when you don’t understand fully what is going on. The real problem with journalism today is that it is very boring. That is why people turned away from it. I don’t buy the idea that journalism is dying because of the internet. I have done research about this and found out that, in my country, the big decline in the audiences of printed journalism began way before the internet rose up as a big phenomenon to challenge it. People have a feeling about journalism that it is pointless to read it. I think journalism has lost its position in the old idea of mass democracy. The old idea of journalism was that it told you about terrible things that have happened which would either make you angry, indignant or sad. Then, together, you the people would put pressure on the politicians and the law makers. This old type of journalism was meant to be moving and mobilizing.

Also, the key thing was that the politicians played a role where they were your bridgeheads into power. The process went starting from you, through the journalists and then through the politicians and they changed forces of power. That was the idea of mass democracy. In the late 1980s, people began to peel away from political parties. They just were not interested. That is partly because of the end of Cold War. But it is also partly because of the rise of individualism. The idea that “I am an individual, I am the most important thing and I don’t want to be part of something” is such an important idea in the modern world. If you are not part of a collective, you are not part of a party, you lose that collective power, and the process begins going the other way. Instead of politicians being our bridgeheads into power, they became the bridgeheads of power into us.

So, in the early 90s, the politicians gave up on having an ideology of holding out another dynamic future world and they adopted the language of economics which basically says “We will show you how to keep the society stable”. This is a discourse that looks at the society as a utilitarian financial system in which everyone plays an individual component role. Economics is all about doing risk analysis and showing the politicians what the dangers are so that they would tell people how to behave in order for the stability to be held. I think you can see from early 1990’s onwards a rise of what I call managerialism in society in which everything from your body to the way you think and feel and your economic behavior is guided. It is not manipulated; it is just guided. Newspapers now fulfill a role of not making you angry but it is actually making you rather worried about whether you are eating the right food, or whether you are buying the right house, or whether you are missing out on options in the stock market. They are sort of information sheets.

So, the system actually just switched. It does not work now. It has changed. The really key question underlying all this, which no one has yet got their teeth into, is: Was mass democracy just a little moment? It was a moment from late 19th century till about late 1990s when people were happy to be part of political parties. I remember it, my grandfather was an old leftist and he was proud to be a member of a party and work together to change the world. It was an old idea. But you have to surrender a part of your identity to that thing. Imagine you were in the Civil Rights Movement in America in late 1950s. People of your age would go down there, white activists would work with young black activists and you would give two or three years of your life to it. No one remembers those people. Many of them were beaten up. Some were killed. But they surrendered. No one would do that now. When people protested in my city against the invasion of Iraq in 2003, three million people marched through the city and their slogan was “Not In My Name!”. It was a very individualistic slogan. Then they went home and that’s it. So, of course, we invaded. What I am saying is that we bear a great responsibility for this because we don’t want to be a part of something. Because of that, politicians said “We don’t want to be part of you”. They switched and got their status from think-tanks, lobby groups and also from science which just gives them information that they deem to be “neutral”. They say “This is what you should tell people to do”. Then Clinton tells people to go out and shop after 9/11. He said that you must keep shopping in order to keep the system working. It is sort of like we lost the ability to get into power and to complain about it. That is why journalism declined. It does not have that function any longer.

You used the word “stability” and the way it was deployed by economists as technocrats in order to change people’s behaviors through certain discourses. This reminded us of the word “sustainability” and how the liberals in the US and Britain takes a stance in alliance with certain green movements like the way Al Gore made a documentary called “Inconvenient Truth”. How do you see this green discourse among the liberals, especially in popular culture, documentary filmmaking and journalism?

It is a massive issue in journalism. It is very interesting how around us, in all sorts of different ways, our models of the world which are all about stability. I made a film called “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace” tracing the idea of the history of ecosystem and where it comes from. It is an engineering idea which is that you can conceptualize nature as a system of energy moving around pipes which is seeking stability. In that film, I argue that nature actually could be anything. Human beings always invent nature to be whatever they want it to be at that time, politically or socially. In the romantic era, in the 19th century, nature was this wild, chaotic thing in which you lost yourself, something that takes you on and this was very similar to the idea of history at that point. The history was marching to an inevitable root towards something because it was dynamic.

Today, we have models of stability. That is not just true of nature but it is true of the internet as well. The tech-utopians from the Silicon Valley argued that the internet gives you a new kind of democratic politics because like the ecosystem, through feedback systems, it gives us all sorts of information. Through that, you get a new kind of discourse of stability without politicians. That is their idea. It is a model of democracy which is a system seeking stability. It does not have a vision of the future because you don’t want a vision of the future as that would imply a leader who says “Here is my vision of the future”. We don’t want leaders now because we are individuals. So, what you have is an idea of democracy where there is no picture of the future, we just want to keep it stable. The problem with that is, who designs the system?

We wanted to ask this because yesterday during the Q&A at Tütün Deposu, you dropped a phrase like “The future scenarios -regarding global warming- are actually part of another pessimistic vision”.

No. Let’s be clear about that. Climate change is happening, no one questions that. That is a fact. There are two ways of dealing with it. One is to realize that here we have a dynamic opportunity to say “This is a problem and we can use it to make the world a better place, we can allocate energy in different ways, we can build a better world on the basis of this crisis”. The other way, which I think has become dominant, is to say: “It is so terrible, we must not change anything”. This is an opportunity to change things in ways much grander than just dealing with this crisis. You can use this crisis to actually make people in the developing world better. You can actually invent all kinds of new technologies, you can be dynamic and say “We can build another kind of future”. Although the Green Movement is much more radical in the rest of Europe, in my country and in America, the idea is a very conservative one. They just say “We must hold the world stable”. They all go on about how many degrees centigrade is allowed to rise. They are like engineers, thinking like a thermostat. Again, it is an engineering model of the world. Rather than accepting that the world is always changing, they want to hold onto the current state in the face of a crisis.

There is no optimism at the heart of the climate change movement that dominates in Britain. The environmental movement in Britain has deep conservative roots. Prince Charles is one of the leading climate change movement figures. That is telling you something, isn’t it? It also has something to do with the liberal middle classes who used to be optimistic but now began to go doomy and dark. I don’t quite know why but I think it is really dangerous. Instead of actually saying “We have a crisis and we must do this and that”, they say “Oh god! There is a crisis, we must do nothing and hold the world as it is”. That’s just unfair on the rest of the world and it is a form of imperialism.

Let’s get back to your filmmaking. In your work, there is a theme that runs through which says “The world is very chaotic and it is being shown to us in a simplistic manner”. Do you think you succeed in reflecting the complexity of that world without losing the details?

There is a fault line in my films. There are times when I say that the world is a more complicated place than politicians think it is, and in many ways, it is far more uncertain. Then, I make a film which is very certain about that. That’s a fair criticism of my approach to this. On the other hand, what I am trying to do is to make people look again through the use of certain filmmaking techniques. That’s why, in “Bitter Lake”, I use shots that normally would never be used in news pieces and I let them run long. One shot that I run for three and a half minutes, some British soldier and a bird playing around his helmet happening somewhere in Afghanistan, aims to make the people look again at the world. I just liked it and let the whole thing run. I was given hundreds and hundreds of hours of unedited material shot by camera men in Afghanistan mostly since 2001 when we invaded. Only tiny fractions of those were ever used in news reports. They just sat in a cupboard for years until a camera man I know digitized them for me. I watched for days and days and I realized that the camera men were trying to tell me something. Not only intellectually but these camera men were trying to show me the mood in the country visually. They were saying, “Look, this is a country that has been in war with itself since late 70’s, it is really complicated and I am showing you this”, as they were sitting in the back of a Humvee, just pointing the camera and just watching. At that point, I realized that this should be the way I should make this film. What I was trying to get at was that this is far more complicated than we imagined. So, you get it almost on emotional level. And I think people like that.

What about your unmistakable aesthetic of using collages of footage?

There are two reasons why I make films like I do. One is to make people look again. The other is to have fun and show off. Not in any flashy way, but if you are a journalist, you are also a showman. You want to entertain people. I have a serious reason for that. I say, “Have you looked at the world like this? I can make the world look like this. It is exciting, so look again”. Sometimes you put shots together that feel right but there is no logical connection. But you take your audience into the mood that you are trying to create in order to make them listen to your argument.

The music you add is another layer.

Yes, it is emotional. I am trying to create a platform, a world that you lose yourself in to communicate what I am trying to say. There are two ways of doing journalistic films. There is one way, a very serious way. You have music quietly going on at the background and natural effects. Then you appear, you talk and you walk around and so on. Or you do what I try to do, which is to say, “Come into my world, this is the world I like. You can argue with me but come with me”. Every shot I put in my films, I like them. I always throw out things and come up with an effect, not because it is functional but because I really like that shot or music. I feel like it fits into the things that I am saying. In a sense, it is emotional propaganda.

I am also trying to show the audience that this is what I am doing. Most television programs don’t pretend to be real, they step back and say “This is it”. I am rather saying that “I have constructed a version of the world”. I am not talking about some post-modern rubbish. I am just saying that journalism is always about constructing a story out of chaos. This is to entertain you and draw you in but also to make you reflect. That is how journalism works. I think the audiences are much more sophisticated these days than many of my colleagues realize. Audiences don’t say “Oh, it is post-modern”, they rather think “OK, he is telling us a story and I can agree or disagree with it”. Actually, that is what my films are there for. They are there to provoke you and ask “Have you thought about what this means?” I will do my best to make you agree with me because I am a propagandist, but I will also give you a warning sign like those on cigarette packs.

Journalists tend to be very pompous and think that truth is like real facts as in biochemistry. But it isn’t. There are two levels of reality in the world. One is just stuff out there that science deals with. A stone is a stone and a compound is a compound. In the world of society and politics, that level of reality doesn’t apply because society and politics is all about creating something. It is an effort of imagination, people dreamt it up. The complex interplay between secular rationalism and religiosity out of which Turkey has gone backwards and forwards in the last few hundred years is a complex work of two imaginations bouncing off each other. My country, a religious country, out of which the left and right traditions came is again a work of imagination. Of course, it is dealing with reality, but those who are in power define the story. Power is not just telling you what to do, power is also telling you what the story of your society is. Societies can be made into other kinds of societies; they are not fixed and run by a sort of inherent machinery. In our age, societies and us are understood as machines, this is a machine age, the gene is a machine idea. For example, Richard Dawkins is not a geneticist, he is a computer coder. If you read his early books, you see a computer software model which ignores the fact that human cells are more complicated than that. The idea that DNA is the code of life has gone deep into modern consciousness, but if you talk to a cellular biologist, they don’t think like that all. So, I just think that the machine model fits with the idea of a fixed and conservative world.

In your Q&A, you said that rather than a dystopia in which machines rule the world, bone and flesh human bodies are being digitalized and robotized. You also mentioned that mass data being collected about people homogenizes things around us. Could you elaborate on these points?

There are a lot of books and articles saying that machines will take over and artificial intelligence will replace human jobs and no one knows what to do. I think it is the other way around. We do live in a machine age where there is big data and I am arguing that the way we think of ourselves as human beings is being simplified to fit with the way machines think. Take the body/mass index. The body/mass index is a simple idea of what you should be and it ignores the complexity of human variation. The origins of the body/mass index came out of anthropology and it has to do with the average weight of a population. It is not a guide to what you should be, it’s a guide to what the average of a population should be. It is also the same with “If you like this, then you’ll like that” mentality. If you look at the recommendations of your friends from social media, everyone is recommending stuff that is very similar. Systems like Pandora or Spotify are feeding back to you stuff you already like. Your choices are getting narrower and simplified rather than having a complexity which you can explore. You become a component in a circuit of information. Is the internet going towards a series of closed systems or is it being genuinely open? The original utopian idea behind the internet was that information would flood through and people would learn new stuff. People used to spend hours putting information up on their personal websites or blogs in the early days of Internet, they don’t really do that now. What has happened now is that you have a closed circuit of networks in which people like you exchange information and anyone who doesn’t fit with that is violently expelled. What you get is a simplification of what you know and what you believe. You become a part of an echo chamber where you all reinforce each other.

What is your take on online forms of media like Vice or online modes of conversation such as Twitter? Do you believe in their potential to shape a new politics?

These are actually very traditional, aren’t they? Vice is good journalism, it takes you places, tells you stuff but it is quite old-fashioned. They were the first people to go to Syria and do very good reporting and I learned a lot just by seeing it. But I have not seen anything new in terms of form on the internet apart from 3-minute films about cats or sneezing pandas. The internet is just another form of transmission; it is a technical system. It is not actually going to change the form of many things. At the moment, most of these places are being colonized by large companies who want to stream films. These films are very traditional and old-fashioned. What needs to happen online is that you need to have good journalism that people want to watch. That involves telling stories in ways that people want to listen. There is also lots of bad or boring forms of online journalism. I think the problem is journalism, not the internet. Yes, there is some good online journalism, but I am dubious about the internet creating a new kind of journalism because I have not seen it. The idea that Twitter is a new kind of journalism is also something I don’t buy.

What about the discussion about the role of Twitter during the Arab Spring and other uprisings?

Let’s look at what happened. The social media was a very good aggregator of people into a space. But when people got to the space, the social media did not tell them what the alternative society they wanted to create in Egypt was. At that point, a group which did have an idea, The Muslim Brotherhood swept in and they carried the day because they had a vision of what they wanted. They got voted in, then they made some very stupid decisions. The generals in power made some ruthlessly clever decisions and shocked them. At this point, many liberals who’ve gone to Tahrir Square began to approve what the generals did. They could not live with the Muslim Brotherhood, so they found themselves aligned with the most reactionary forces. The idea that the social media is a revolutionary force is a confusion of a technical system with an ideology. You need a powerful and imaginative ideology or a picture of the world. You cannot call a technical engineering feedback system which seeks stability an ideology.

You recently collaborated with Massive Attack for a movie and there was “It Felt Like a Kiss”, a theater exhibition where you worked with Damon Albarn. Tell us about your relation with music.

I steal ruthlessly from music and I always have because I love music. The thing that has always baffled me is that most people that make documentaries have such rubbish music, especially in the BBC. Everyone has their musical taste, but somehow when they come to make their films, they don’t actually allow their own musical taste in. They think, “I should have some skittery drum and bass at this point because everyone is being a little skittery”. Or “I should have some sad Arvo Pärt music here because it is all a bit sad”. You get the same music all the time. The worst one is that if they are doing something on finance, they play “Money” from Pink Floyd. That is the bottom. They are not really allowing their own taste to come through, they go on with what they think is right. I know these people and I know very well that they’ve got as complex a musical taste as I have. All I have done is using music that I feel at that point is right and is not a cliché. For example, I use Burial because he takes noise and makes it romantic. I have always thought I am quite normal and if I like music and I think the music goes well with that picture, then the audience will like it. It has to be honest and intuitive. I spend most of my time throwing out of stuff, trying out things. For example, I have discovered that you cannot ever cut a piece of film to The Cure, they are beautiful but they are an impossible band to cut to film, it just doesn’t work. But Burial works and Nine Inch Nails works. I have used a David Bowie song in “Bitter Lake”, but his music is also too self-contained. People know it so well, they have their own view of the music, you cannot use songs that people have possessed themselves. I also used to use early analogue electronic music but not anymore. I like romantic stuff, like Cliff Martinez, the stuff he did for the movie “Drive” is really good and I used some of his music in “Bitter Lake”. Today, you get whole genres of music and albums that are now built to be in films, like indie music. That is what corrupted indie music. It became twee and that goes back to what I said about how we’ve become like children. Twee doesn’t even have the energy of pop music, pop music like Rihanna is great. But I don’t like Beyonce.

What did you think about her recent Super Bowl performance of “Formation” and her deploying power politics into a big media event?

It is one of her better songs. It was fine, it was a gesture. I don’t know why they would criticize her. Why can’t a black woman shake her butt if she wants to and yet at the same time have a revolutionary politics? It is somewhat puritanical to judge it. You are giving me the puritanism of the left there.

Your point makes sense because you say that some of the reactionary stances among the left are deeply conservative.

I have a really bad theory that the real conservatives of our time are the liberals because they really don’t want the world to change. With the conservatives, you know what you get. They tend to be more ruthless, they tend to be more honest about power and you know what they are up to. What I want to open up in my discussions and films is that many of the liberal ideas of our time are actually deeply conservative. I made a short film about the rise of a thing called “Oh Dearism” for a comedy series. In the past, the liberals wanted to change the world, they had this optimistic view of the world. Somewhere in the 1980s, they switched. What they would do is read the newspaper in the morning and go “Oh Dear”. And that’s it. The liberal imagination is incredibly powerful in modern society because they are highly educated, very articulate, well connected to the media and other information outlets. They have a big power of influence and in a way responsibility. Yet somewhere in the 1980s, they retreated into a pessimism. I presume it is something to do with the economic failure of the 70s and the rise of the right in the 80s. As I said, same thing goes on with climate change. There is a crisis, we can really use this and be dynamic, but they go “Oh Dear, let’s just hold the world stable”. As a result, you get these risk models coming along, they love risk.

It was after Chernobyl, this man called Ulrich Beck wrote a boring book named “Risk Society”. It is the most reactionary thing you could read in your life. It is all about how politicians used to be about allocating resources so that the well less-off people get more resources. Now, it is “Let’s allocate risk, so that we have less risk”. Instead of saying “Let’s make a better world, we are now saying let’s hunker down in embrace position”. Like in those diagrams in aircrafts about what you are supposed to do, you go in embrace position.

Why do you think liberals accepted this embrace position?

I still don’t know why they’ve done it. I have a really nasty theory that it is a way of maintaining power as power moves away from them. If they say they want to change the world, they should do it. I am not talking just about the academics, artists or journalists, it is all the liberal classes who still maintain that they want to change to world. It is the people who marched in London and then went back to their home and did nothing about Iraq. In my country, there is probably a third of the population who you would say that they have a genuinely progressive idea of the world. But they’ve retreated into a pessimistic view of the world where they are terrified of their bodies, the food they’re given, the risks and dangers outside and they’ve frozen. When I did “Power of Nightmares”, I tried to touch that problem and say “Yes, terrorism is frightening, it is a danger but it is not overwhelmingly apocalyptic for us”. But they wanted it to be apocalyptic.

I am an optimistic person and I believe if you are on the left, you should try and work out how to change the world. The really astonishing thing about our time is how again and again you have movements rising up who say they are going to change the world and then nothing happens. Take the Occupy movement. They had a great slogan which drew people’s imagination way outside the liberal base and then they blew it. Because they had no idea about the type of society they wanted to create. Then, you had Tahrir Square which was an amazing opportunity and that they failed. What happened to the opposition in Gezi Park? In a way, it never was able to get traction. Obama’s main slogan was “Change”, I was very optimistic about it, but what happened? We went back to exactly where we were before. He put the people who were responsible for the crash in 2008 in power. You may say that the Occupy movement paved the way for Bernie Sanders. I thought Occupy could be the beginning of a modern opposition whereas Sanders is good but it is a throwback to the old times, it is like going back to a retro shop. What I worry about in my country with Corbyn and Labor Party or Sanders in America is whether it is nostalgic. The people who support Donald Trump are also nostalgic about a moment when the businessman was a hero. I worry whether the left is engaging in an equal nostalgia for the radicalism of the 1970s which fell apart and went to what is called identity politics. It was good, won a lot of battles and changed our views about racism and gender; but it went off down one way and it didn’t manage to deal with big forces of power. Syriza was a puzzle to me, again it had a very strong movement behind it and then what happened? It gave in, I still don’t understand why. Podemos? Nothing ever gains traction. Maybe Sanders will, but I worry about whether the same thing will happen with the Occupy Movement and we will go back to our default position. It is a puzzle to me why there is no change despite the fact that there is a lot of hunger for it and dissatisfaction with what is going on at the moment.