"We are biased and we have an agenda": Joris Leverink

Joris Leverink is a freelance journalist with a background in cultural anthropology and political economy. In addition to writing articles for various alternative media platforms, he is also one of the editors of ROAR Magazine. He has been calling Yeldeğirmeni home for the last couple of years. We met with him and asked him questions about freelance journalism, alternative media and Turkey.

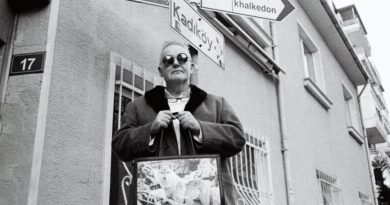

Interview by 13melek, Illustration by Sadi Güran

Let’s get to know you first. What brought you to Istanbul?

I did my masters in “Political Economy of Violence, Conflict and Development” at SOAS in London. My thesis focused on the political conflict in Mali. My idea was to move to West Africa and start working as a freelancer there. But since I happened to find my girlfriend here, I instead moved to Turkey about two years ago. When I came here, I was not aware of the political situation at all. I was in Istanbul in the summer of 2013 to visit my girlfriend. I returned to London on the 28th of May and when I checked my Facebook, I saw that the Gezi protests had started. I thought I should have been a part of the resistance but since I did not have the means to do so, I followed everything very closely from London. That’s actually how I got more involved with ROAR Magazine. I started covering the Gezi events for ROAR, posting regular updates on Facebook. It was only a couple of months later that I moved to Turkey. My involvement here started by meeting up with different groups in the aftermath of Gezi and getting involved with various struggles. Currently, I am focusing more on the Kurdish struggle and writing a lot about Rojava. I mainly write political and economic analyses from a radical point of view for a range of independent media.

As a freelance journalist, what is your take on the dilemma between the flexibility that being a freelancer provides and the fact that you need to sell your work to survive? Are there structures for solidarity between freelance journalists?

Let me talk about my personal experiences. I haven’t been working as a freelancer for very long. In the past, I had been writing in the sake of political activism, which is still the major part of my writing. At ROAR, we have a small budget for the redevelopment of the website but the editorial work is voluntary. I recently started making some money by writing for other outlets but it is still not enough to sustain oneself. I’ve been working as a bicycle tour guide for a one-woman company in the past year. This job helps me sustain myself and gives me enough freedom to dedicate the rest of my time to writing. For me, working part-time as a guide and keeping busy with my activism is a good combination as I refuse to sell my labor to a company that I politically don’t agree with. If I’m able to work any odd job to sustain my activities that I perceive as more valuable, I don’t see that as a failure and I don’t feel like I missed out my opportunity to build a career. Even in my writing, I refuse to compromise if a certain outlet refuses my articles. There was one example with TeleSUR two months ago when I wrote an article about the history of the Rojava revolution and it was refused at first on the grounds that it was too critical of Assad. TeleSUR – a pan-Latin American news network headquartered in Venezuela – did not want to bash Assad strongly with an “enemy of my enemy is my friend” mentality. One can slightly change an article for the greater good if it does not undermine the main message but I refuse to censor myself. In the end, the article was published in TeleSUR.

I do not know of any solidarity networks between freelancers. This would also be a very difficult thing to create as well because freelancers are per definition living on the edge and it would be hard to have a collective that has a fund-sharing agreement. But if one outlet refuses your work based on some reasons, then you can have a group of people refusing to work with this outlet to show solidarity. There are channels for this on the internet such as the Vulture Club page on Facebook where a lot of information is being exchanged among freelancers.

What about Contributoria, which is another outlet that has published your work?

Contributoria is a website set up about a year ago which offers freelance journalists the possibility to write independent from any editorial guidelines and actually make some money with their writing. Contributoria has the financial backing of the Guardian Media Group. If you have a proposal for an article you want to write, you subscribe for free and upload your proposal. Then, the community decides which proposals get sufficient backing to be actually written. Each proposal requires a certain number of points based on the amount of money the writer is demanding and the proposals that collect enough points are written. The dark side is that it is very easy to “hack” the system and there is nothing that stops a writer from calling his or her friends, asking them to subscribe and donate their points. The platform is probably designed in a way that actually expects the writers to reach out to their friends as part of their marketing plan. I have written a handful articles for Contributoria but I have been less enthusiastic about working with the system since the conversion rate between pounds and points steadily increases. So, every month you have to go around the same group of people asking for their support and this got me uncomfortable. Another problem is that the community-based editing mechanism does not work. Despite these, writing for such a medium opened up new worlds for me. After writing more activist pieces for ROAR, which has an audience with a similar stance to me, Contributoria provided me with the necessary exercise to write for a broader, less politicized audience.

Until now, we have talked about how a freelance journalist can sustain oneself. How can outlets such as ROAR Magazine, that have non-profit agendas, become sustainable in the long run?

This is a very crucial issue that we have been dealing with constantly. At ROAR, we have only three full-time editors and running the website requires a lot of time. The first thing you need is people willing to donate a lot of time. We will never allow any commercial advertising because it will undermine the very message that we are trying to convey. So, that means we have to look for funding from other sources. We tried to run a crowd funding campaign last year and we also applied for funding from the Dutch Foundation for Media and Democracy, which granted us a fund that will allow us to build an online magazine and launch a quarterly print magazine. For one year, we have enough funds to reach these goals. But how to sustain the magazine in the long run is difficult to answer. There are so many digital media outlets that people expect everything to be free. If everybody who visited ROAR donated one dollar per month, we wouldn’t have to worry about anything. But this does not happen. It’s not that people don’t want to spend the money, but the anonymity of the internet and the existence of so many outlets that provide everything for free discourage people from paying.

You mentioned the editorial structure of ROAR Magazine and the contribution of volunteers. What is the mission of ROAR Magazine and what topics do you cover?

ROAR was founded by my comrade Jerome Roos as a personal blog in 2010, right before the start of the Egyptian Revolution. Then, people started sending their articles and it started to grow from there. I got personally involved during Gezi when Jerome asked me to take update the Facebook page. That was really the turning point for us as the reach we had went up from 16 thousand to 2.5 million during the month of Gezi. We all take our inspiration from autonomist, anarchist, leftist and libertarian traditions. We are biased and we have an agenda. Our agenda is that we support and promote the different popular uprisings that have sprung up across the world in the last few years. It started with Egypt and it really kicked off after Gezi but, in the meantime, we have also covered the Syntagma occupation, the indignados in Spain, the Occupy movement and the global financial crisis.

We were very excited to see the people’s forums springing up across Istanbul because these are the kind of direct and horizontal democracy movements that we are supporting. We are trying to convey the message that all these different struggles have something in common. Although all these struggles are covered in the traditional media, it’s very difficult to see the connections. This reminds me of one photo I have seen from the Brazilian protests just after Gezi. In the streets of Rio de Janerio, there was a Brazilian guy holding a Turkish flag and kissing it. This showed for me that this guy had understood what the majority of the people that are just following the mainstream media failed to understand – that there was a connection between these protests.

We do not just cover a struggle if there are a million people on the street but also we explain why these people take to the streets. What are the underlying social currents and the political economic history? What are the demands of the people? How do they fit into a certain political ideology and with the zeitgeist of today? We are trying to build these connections and I believe ROAR plays an important role in this sense. Right after Gezi, we also covered the movements in Brazil, Bulgaria, Bosnia, etc. In this way, those people that started following ROAR because of our coverage of a specific struggle are introduced to similar resistances around the world that they otherwise may not have heard about. People may like the coverage and political ideas being expressed about Gezi, so when we write about the workers’ uprising in Tuzla (Bosnia), they may find it to be something that is of interest to them as well. When protests in Ukraine, Thailand or Venezuela happened, we did not jump on the bandwagon and start waving flags for another popular uprising. We looked at what was going on, analyzed the situation and realized these are not struggles that fit in with what we are trying to fight for.

What really makes a medium alternative? Is it the editorial focus or is it the institutional structure?

I think it is a combination. It starts with how you organize yourself. Because we have such a small team at ROAR, we can still make all decisions based on consensus. We realize that with a larger group this would be hard to sustain but it is a 100% horizontal organization for us. I would not go as far as saying that a hierarchical organization cannot be an alternative outlet per se as things are not just black and white. What I am trying to say is that it would benefit the content of your outlet if you are practicing what you preach. If you are preaching horizontal democracy, alternative ways of organizing and anti-authoritarianism, then having an internal structure that still maintains old hierarchical forms of organization may be problematic. Being an alternative media also has to do with your coverage and also with your funding. If you are limited to funds coming from big media corporations, government institutions or influential individuals, then you’re bound and these boundaries feed into what you can cover. Also, we need to shed the cloak of pretending to be unbiased. We have a political agenda and we’re there to bring the news to the people with a certain political analysis.

Net-neutrality regulations that may potentially limit free expression on the internet are being discussed in the US. How do you perceive the importance of internet on the existence of alternative media?

I cannot comment on the specifics of those regulations as I am not an authority on the issue; however I do have some things to say about the usage, privatization and surveillance of internet. I think that in this time and age when there are so many options available to express and organize ourselves, the more freedom there is, the more repression there is. We are no longer being shielded by the anonymity that existed before the net when you could talk with friends and make political expressions in the relative safety of a coffeehouse or a political gathering. Now, when you publish a Facebook status or when you tweet something, it’s there and will be saved somewhere forever. A good example is Turkey where many people are being prosecuted because of the things they tweeted. It’s a double-edged sword. In one sense, it places the power in people’s hands in terms of much more possibilities to express oneself on an individual level. On the other hand, it’s much more controlled because everything is saved, shared checked and analyzed right away. As an activist, I wish there were good alternatives to such online platforms, but there are not. With ROAR, although we have a very clear anti-capitalist agenda, Facebook is still one of our main sources of visitors to our website and we in a way we are forced to use it. In a sense, you need to use the weapons of the enemy in order to fight your own struggle. That does not mean that you just dive in blindly and take whatever comes, you need to be careful about your net security. But these are the best instruments that are available to us and we’re not left with much of a choice, how ironic that may be.

You recently wrote an article criticizing the Turkish prime minister about his attendance to the leaders’ walk after the Charlie Hebdo killings and the raid of a newspaper office that published the cartoons one day later. How do you see the freedom of press in Turkey?

As we all know, freedom of press is practically non-existent in Turkey. There are independent outlets and social media platforms that say whatever they want to say, but they also run the risk of being prosecuted. Take the example of the autonomous alternative media platform Ötekilerin Postası whose Facebook page got shut down time and again. When the government closes Twitter, Facebook or Youtube, for me this shows that they lack a basic understanding of the consequences of these actions. They just make a fool out of themselves in international circles and are oblivious to what extent they are shooting themselves in the foot. Even for me as an international journalist with a European passport, I realize that I’m not safe. In Turkey everyone that engages with critiquing the government in any way is a possible target. Just look at the case of Frederike Geerdink, a Dutch journalist based in Diyarbakır who writes a lot about the Kurdish issue. She was prosecuted for “making propaganda for a terrorist organization”. Based on what? Based on a photograph of a demonstration in which a PKK flag was visible which she shared on social media. Of course her prosecution was just a case of intimidation, but it shows to what ends the Turkish government is prepared to go to prevent any coverage of sensitive issues that differ from the official propaganda. Geerdink’s prosecution made me realize that I could easily be singled out as a target too, simply for writing articles that are critical of the government.

You’ve been observing what’s happening in Turkey for a while now. What’s inspires you the most about the future of this country?

Without a doubt, it’s the Kurdish movement, particularly the movement towards a democratic autonomy in North Kurdistan and the social revolution in Rojava. On the one hand, it’s emblematic of the age-old struggle of the oppressed against the oppressor; it’s the story of resistance, which appeals to me on a personal level. On the other hand, the shifting focus of the PKK – leaving the aspirations of founding an independent state based on Marxist-Leninist ideology and instead fighting for democratic autonomy, where people organize themselves all the way down to the street level via neighborhood councils and such – is inspirational. I really see that this struggle has the potential to be an example for movements around the world, in particular the events in Rojava right now. The revolutionaries and activists marching down the streets and discussing their ideas in the West for a long time are being shamed by this group of people who are standing up and implementing what everyone has been talking about in the middle of one of the most brutal civil wars that we have seen for the past few decades. They have put their money where their mouth is by fighting for gender equality, women’s rights, environmental sustainability and horizontal democracy. They are fighting against century old institutions of centralized government, hierarchical institutions, patriarchal society and capitalist modernity. Yes, they are also fighting against the Turkish state, the Syrian state and ISIS, but the goals that they are fighting for are so universal that they can’t be limited to the Kurdish regions alone. This struggle should be fought anywhere by anyone.