On “militarized” cities with the Funambulist Magazine

“Let’s try to build architecture that challenges the relationship of power within the society.”

Interview by 13Melek, Neyir Erdoğan, Photo by Léopold Lambert

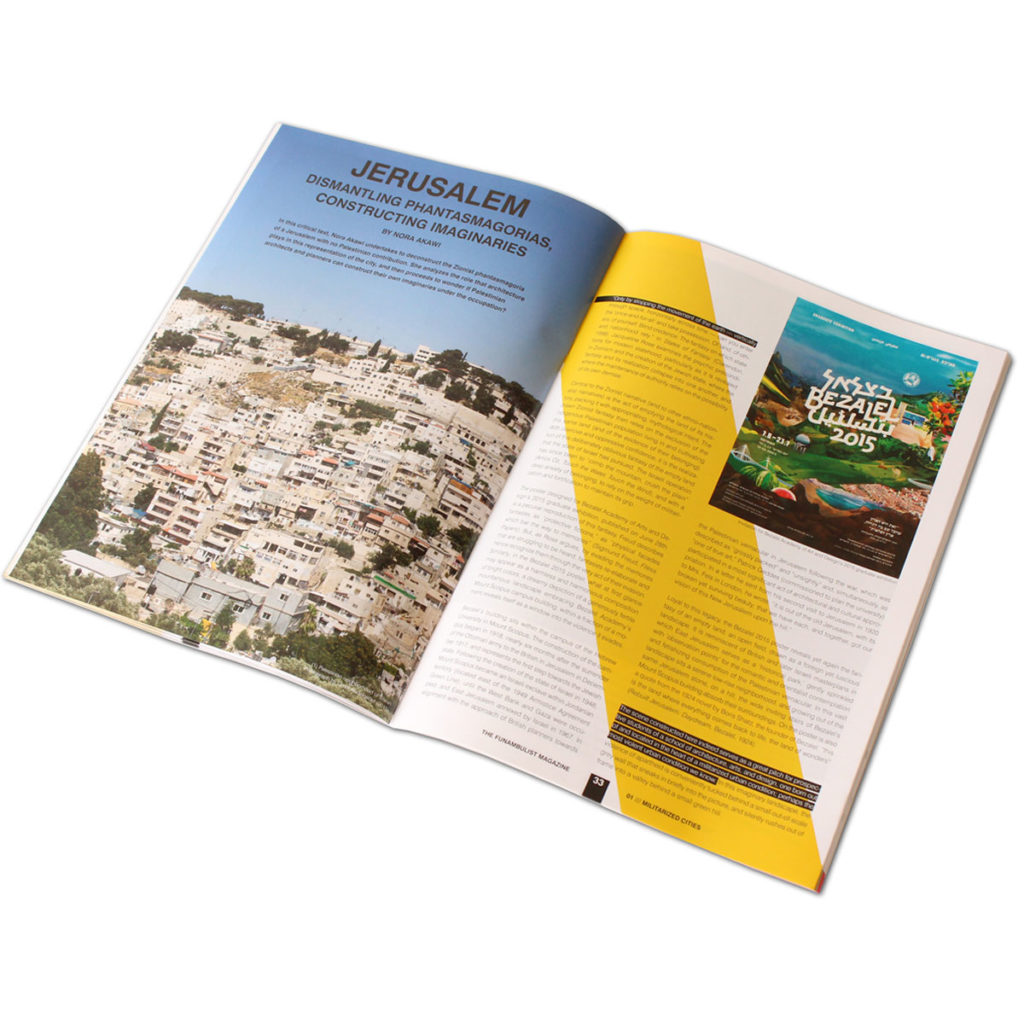

Paris and New York based architecture, writer and editor Léopold Lambert has been discussing the politics of architecture through blogs, podcasts and books. He started supporting his blog named The Funambulist with a podcast called Archipelago about two years ago. And The Funambulist has also recently started to act as a bimonthly printed and digital magazine created around a certain theme. The theme of its first issue is “Militarized Cities”, and we decided to chat with Lambert around this subject.

Let’s begin with Funambulist. What topics do the magazine focus on? How do you operate as an alternative media outlet?

We should begin with the name itself. A funambulist is tightrope walker. I particularly like this figure but (s)he walks on a line, architects’ medium, and, in doing so, (s)he disrupts the original intent of this line that splits a given milieu in two and forces bodies to be in one of them. The funambulist is not liberated from the line, (s)he just subverts its effects. I’m trained as an architect myself and I’ve been interested in bringing humanities and political activism within architecture and bringing architecture to these other worlds. The editorial line consists of asking a certain amount of questions around the political relationship between design and the bodies. Funambulist started as a blog, an open access media in 2010. In 2014, I started a podcast called Archipelago, which is trying to find other ways to share or produce non-institutionalized knowledge. Finally, the most recent project is a magazine that attempts to question one topic each time and mobilizes talented and young people around the world to approach these questions. The printed version does not replace the open access platform but rather complements it.

We can move on to the first print issue, which is on militarized cities and presents case studies from around the world. One point you make in your introductory essay is that the violence of military organization of the city does not come from outside and the way the city is built contains the violence itself. Can you elaborate on this statement with examples?

When I talk about militarization, I mean something larger than the institution of the army. This also involves the police and, even more broadly, any form of policing or control. The main point of the case studies is to say that all cities are militarized to a certain degree. I can talk about three examples, which are very different in terms of timeline. It’s an academic cliché by now that the transformation of Paris during the time of Napoleon III that was done by Haussman between 1852 and 1870 did not only make the city more bourgeois with a hygienist agenda but it also had a militarized one. Obviously, in Paris of the 19th century, insurrections were regular and they tended to happen more easily in dense, labyrinthine and proletarian neighborhoods rather than the boulevards and avenues in Hausmann’s vision that enabled the army to move very fast. If we move to the 20th century, we can give the example of Brasilia. Brasilia was not designed for dictatorship as it was inaugurated three years before the coup d’état of 1964. However, whatever the original intent was, the fact was that the city was holistically planned and this was obviously a very big asset for the military making the city easier to control. Without this transformation, the military dictatorship may have not lasted 21 years as it did. A third example belongs to the 21st century. We know how much potential Cairo has to gather bodies in public spaces since 2011. So, the current military government of Egypt is planning to build a new capital city in the desert outside of Cairo where the public space will be much more controlled and there will not be any working class housing. I think it is also important to note that the city is being built by a single architecture office (SOM), so it’s interesting to see the collaboration of architects with the government.

In our daily lives, we routinely encounter things such as walls, barriers, bag inspections, etc. We may not really think about these mechanisms as a part of militarization since we have come to accept them. How does the public opinion react to such simple vehicles of violence? Are they regarded as justifiable defense mechanisms?

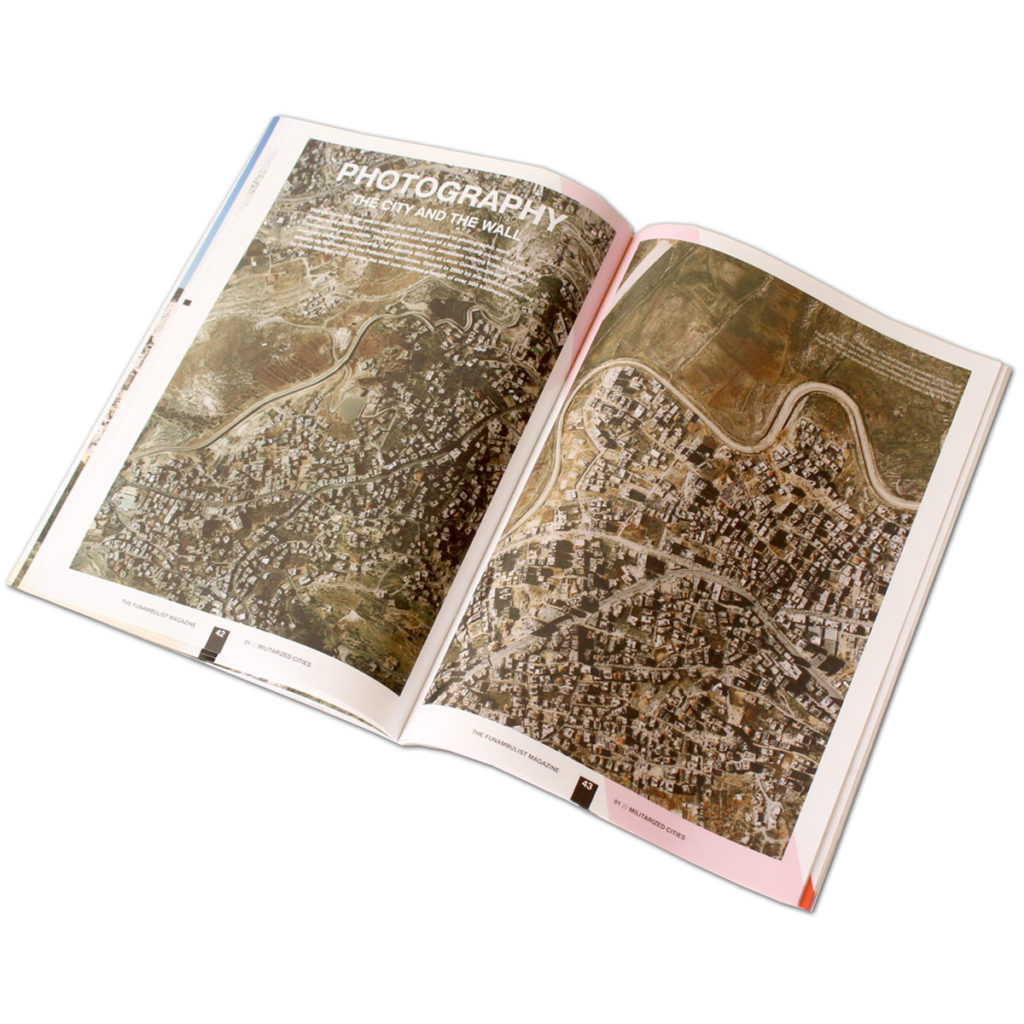

This question touches the rest of my work regarding the intrinsic violence of architecture and how, for example, a wall can never be innocent. A wall is a very strong apparatus in the organization of public space. We are very much used to this violence because we are surrounded by walls all the time. We are inside a room right now; we happen to have the key to the door so we don’t really feel like we are in prison but essentially there is not much difference between a prison and a private room. Whoever does not have access to a roof very much understands the violence of walls. When you have to sleep in the streets, you understand that walls are against you. In general, we are surrounded by this violence and we don’t necessarily pay much attention except if we are inevitably confronted by it. When it comes to military intervention in the city, it is a very similar process and therefore it’s sometimes quite difficult to feel like we reached a critical point where we no longer can accept what’s going on in front of us. We often just let go because the process is so gradual except when there is a big state of emergency. A state of emergency usually follows an emotional peak like we had in Paris in January. I have never seen the police in France having machine guns until recently. I’m not sure when they are going to revert to simpler gears. So, I think there is something gradual in the fact that we are very used to seeing violence around us without really seeing it and the more privileged you are, the least you see the violence. But there exist also some leaps that correspond to crisis periods, which legitimize violence.

One of the articles in the issue writes “towns with large military presences suffer from cultural depravity, violence and drug-use at higher rates than national averages”. Which way does the causality run here? Does the state really make the city safer for its citizens?

To be clear, this quote is by Zulaikha Ayub in a student project that looks at military bases in Aurora, Colorado. She actually did this project just before this man killed 12 people in a Batman screening in Aurora in 2012. Thus, the city was at the forefront of problems related to guns and weapons. I cannot speak for the statistics that she collected herself; however, I can clearly say that antagonism calls for more antagonism. France is about to bomb Syria again, Turkey is pretending to bomb Daesh but they are bombing the PKK and more antagonism will always bring more antagonism. I think the same thing works with architecture. The more you build an environment that tends to favor fear and securitization, the more you will invite violence in the environment.

Photo: Leopold Lambert, 2015

A theme that runs through the issue is that militarism is not posed uniformly on the society and it plays on the class divisions many times enforcing these divides. Can you talk a little bit about this issue?

I think the article that puts its finger on this issue is Sadia Shirazi’s article about Lahore. When the US started the so-called war on terror, they found an alliance with the Pakistani government and there were many bomb attacks in Lahore as a result. She noticed how the victims of these attacks often were not the higher social classes, which have means to protect themselves through checkpoints or private security forces. To prove her point, she also mapped the attacks to show which neighborhoods were more exposed to the attacks. So, militarization is definitely following the societal schemes of division of power and, as usual, no one is equal when it comes to securitization. This process reinforces the social gap between classes and between racial groups as well.

Speaking of class issues, can you talk about the different gate typologies in Parisian neighborhoods you covered in a recent blog post?

Manuel Valls, the French prime minister from the Socialist Party (there is nothing socialist about his politics), is very eager to bring security up. But, in January, he actually used the notion of “apartheid” to describe the situation in the French banlieues. Obviously, being someone who works a lot on Palestine and who is interested in the urban history of South Africa, I cannot accept the word “apartheid” to define what’s going on in the banlieues. The word cannot apply as a pure essence, but there is indeed something along those lines in terms of spatial and social segregation. In Paris, you have a city center that we call Paris, which is only one fifth of the city’s inhabitance. The article is addressing the highway that surrounds the Paris municipality. We can call the municipality a fortress because, in the 50s, fortified walls were transformed to a highway that separates the suburbs from the city center. What I came to notice is that the architectural typology that allows you to cross this border is different depending on whether you come from a poor or wealthy municipality. When you come from a wealthy one, the highway tends to be buried and there is a bridge that allows you to cross it, but when you come from a poor municipality, you have to walk under the highway through dark and smelly passages. Not so many people really have to cross this border by foot, so we’re not talking about the daily lives of several hundred thousand people but what is crucial is what it implies for the way Paris constructs a relationship to its poorest municipalities. In general, I am interested in taking Paris as a whole rather than focusing on the city center and making maps about how access to transportation varies depending on where you are, about the average income per municipality, and which municipality respects the law that requires it to have at least 20% of the totality of its housing as social housing. Many of these social housings are what we call the cités, the particular neighborhoods with vertical and “horizontal” towers that eight hundred thousand Parisians live are inhabited almost exclusively by people from the working class, very often coming from former French colonies in Northern or Western Africa during the immigration waves of the 1950s. The history of colonialism is still involved in the way French society is built today.

Recently, the president of Turkey convened “heads” of neighborhood and urged them to report any suspicious activities that they observe. Linked to this, we have seen mobs of men taking to the streets and attacking buildings of the Kurdish party and different media outlets. Is it safe to say that ordinary citizens are also getting integrated in the security system?

Absolutely yes. It’s like the New York subway publicity which says “If you see something, say something” meaning if you see something suspicious, report it to a cop. In the first issue, we have an article about Beirut and the particularity about Beirut is that besides the strong army apparatus, there are many militia groups such as Sunni militias in West Beirut, Hezbollah ones in South Beirut, none of which not dependent on the army. Turkey and many other countries have experienced similar processes and even though people may not have weapons, there is systematic self-policing within the society. This is more complicated because this is more of what I would call a transcendental way of having control. The architects, politicians, engineers and technocrats or whoever we can think of, control the plans of the city whereas when a self-policing scheme enters, we have to see that the consequences on the city can be more subtle yet just as implacable.

During the past year, harsh anti-protest laws have been enacted in Turkey and police have been given unprecedented power to interfere in public protests. Very recently, in Cizre, a city in the southern east part of Turkey, a nine-day curfew was declared with concurrent state of emergency declarations in multiple municipalities. How does the state use such changes in the legal framework to establish the mechanisms of militarization?

Without being specific at all to what’s going on in Turkey, despite my great concern for it, I think some things are relatively common to all places. Everything related to the architecture of the city is ready to implement a curfew. What I mean by that is a curfew is nothing else but you not being able to leave your home and therefore becoming a prisoner of those walls that you thought were protecting you so far. It’s almost like the reversing the violence. So, states of emergency definitely allow this to happen without any modification in the city physicality. I think this shows how we are living constantly exposed to this potential violence without even thinking about it. To be more specific with examples, in the current issue, we have a transcript of an interview with Philippe Theophanidis about the 2013 manhunt in Boston. All of a sudden, we had entire cities shut down with people being somehow prisoners in their own places for one day and the police searching houses one by one with full gear as we know how the US police are being supplied by equipment that comes from Iraq. What I was interested in asking Philippe was related to the fact that even though the police was looking for one man in particular, they were searching every home: all of a sudden they have full access and power to do everything they cannot do on a legal basis normally. I am interested in how much knowledge is being produced in that moment. So, a state of emergency reinforces the power of walls that are there to materialize private property and the forces of the state of emergency such as the army, the police or the doctors are able to deny anything about private property. To go back to Turkey, the part that was left out in the magazine from the conversation with Philippe is about Istanbul and the teargas warfare during Occupy Gezi. Philippe was saying that, during Gezi, what was controlled by the police was the atmosphere. Our bodies need to breathe and we tend to think that the skin is the ultimate limit of the body, and that we can only get hurt when we are touched directly. But actually in Gezi, what happened was that the atmosphere was made toxic and its violence was as effective as batons.

You just mentioned the production of knowledge for the Boston case. One interesting article in the magazine is related to the AT&T switching center in Oakland. I’d like to know what role the cloud-industrial complex and new technologies play in the establishment of militarized cities.

You are referring to the article written by Demilit. What I found great about the article is it points out that what we call new technologies actually have physical belongings. These things are not immaterial. The New York Stock Exchange is in a big warehouse in New Jersey. I think that I read somewhere that to make the internet work; we need about 36 nuclear power plants. That really shows the materiality of things that we assume too quickly that they are immaterial. In the case of Oakland, you have this gigantic building which is very much like a bunker that even has exterior camouflage in the form of fake windows. Demilit starts from this tower and shows all the other apparatuses of control and securitization in Oakland. As locals of the city, they have been doing guided walks around the city and they have been there for the Commune of Oakland, so they know how this place is systematically policed. They also describe how, for example, the city center is full of microfilms that are able to track where a gunshot came from in the case of a shooting. What’s important to say is that Oakland is a particular city in the politics of US. It is the little brother of San Francisco, but it is also the little black brother since it is an important place for the African-American struggle as the city where the Black Panthers were born. During Occupy, it also was a very intense place. Because of these things, the police allows itself to become much more violent than other cities.

To sum up, how would you define architecture and what responsibilities fall on architects and city designers?

I usually say that architecture is a discipline that organizes bodies and space. What that means for architects and designers is that once you say architecture is necessarily violent and political, it’s not for architects and designers to shy away from this responsibility. My point is that we should understand this violence and appropriate it. Let’s try to build architecture that challenges the relationship of power within the society. This requires architects to have a deep understanding about the context in which they are acting. It is a cliché again but obviously the more architecture is not an author discipline but, rather, a collaborative practice, the more we have chances to challenge the control of the bodies it involves.

What topics will you cover in your next issues?

The magazine is published once every two months. The second issue will be about suburban geographies with case studies in US, France, South Africa, Brazil and Palestine. The third issue in January is changing the scale of design by focusing on the politics of clothing. I’m interested in considering several scales of design without thinking that urbanism is more important than industrial design or fashion design, but to look at how all these scales of design affect bodies. The fourth issue in March will be about carceral environments. You may be interested in knowing that Banu Bargu from the New School in New York will write about hunger strikes of political leftist prisoners in Turkey. Also, one of the last Archipelago podcasts is with her and you can listen to it on the Funambulist website.