Simon Menner - If it’s true Big Brother is watching us, we’re not sure what he sees…

We chatted with the artist Simon Menner, who with his book Top Secret shows an internal view of East Germany’s surveillance agency Stasi with awful images from the archives.

Interview by Leyla Aksu

Originally posted in Bant Mag.’s December 2013 issue.

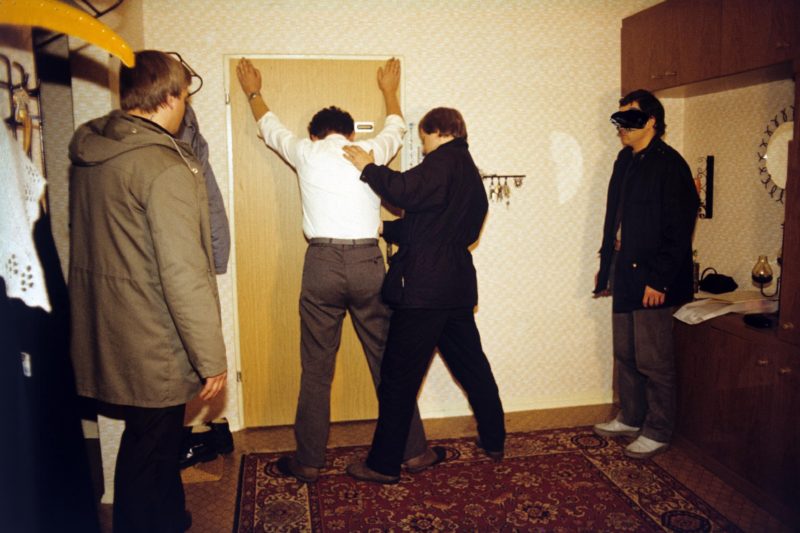

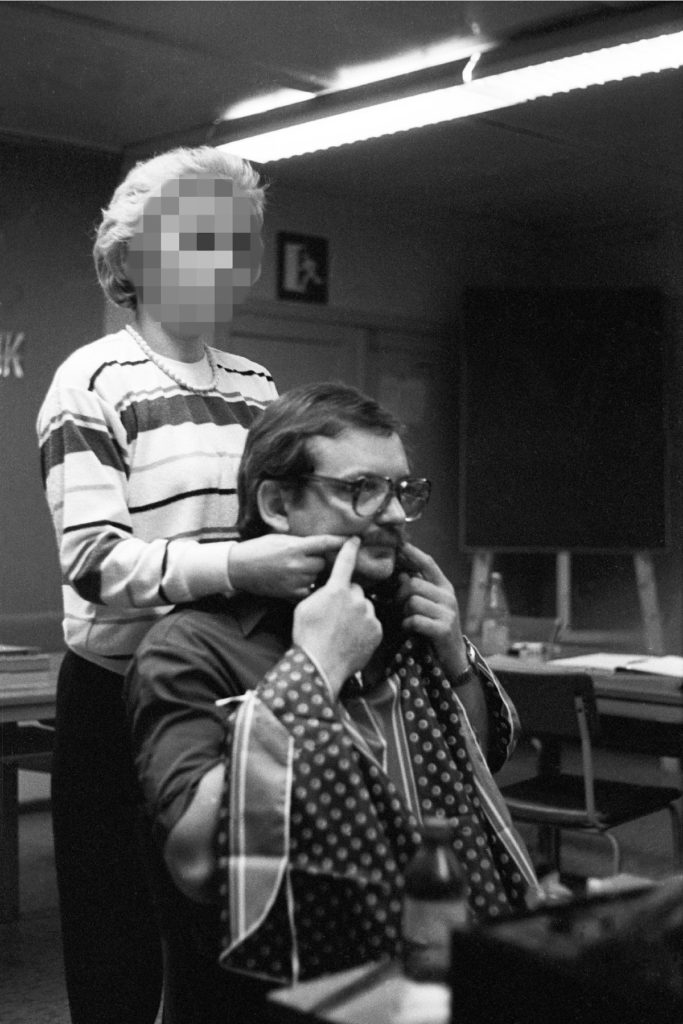

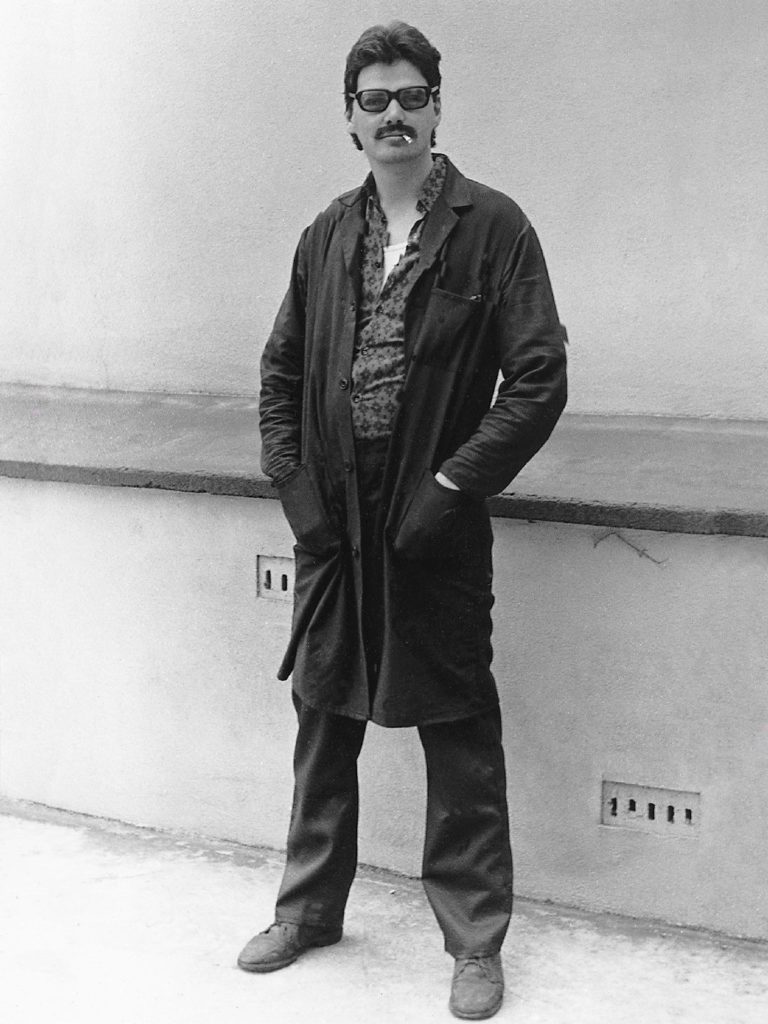

German photographer Simon Menner is an artist heavily influenced and intrigued by the idea of surveillance. In his latest curated book titles Top Secret: Images from the Stasi Archives, he takes a look at East Germany’s surprisingly wide-spread surveillance agency. The images in the book selected from millions of available Stasi documents include topics such as how to shadow someone, fighting techniques, how to put on a fake mustache, and apartment searches. Yet even though these images come from recent history, the world of Top Secret is at once familiar and strange and it holds a mirror to what is going on in society today. There’s a lot to learn from Menner who claims his participation in the whole debate surveillance and why surveillance is not going to end very soon…

Where did the idea for Top Secret come from?

My background is as a photographer, an artist; I studied art in Berlin. Normally I take my own pictures, but I’m very interested in how images are used and utilized as a means of influencing people. So how are we influenced by the images we approach? How is this used to direct our actions? And so on… I’m very interested in the idea of images and surveillance; how they’re used within the surveillance system. I came to realize that I could find so many books and essays about what surveillance is supposed to be, but actually it’s very very hard to find images of surveillance; it’s almost impossible. In a catchphrase: If it’s true that Big Brother is watching us, we’re not sure what he sees. So what does he see? What can he see while he’s watching? So I was very interested in whether there was an archive where I could find something, and yes there is, as the book shows.

Were you surprised by the images and also the extent of documentation that you found? What was the process of acquisition like?

Yes, definitely. My first approach to the archive was: “Does anything still exist?” Because, you have to keep in mind, when I started the project the Wall had been down already for almost 20 or so years and normally you’d think that everything that can be said about this system, should have been said before. Because there’s 20 years of research that went into this archive, so I thought maybe a few little things do exist. Then I stumbled upon a number, that they had some two million pictures. And I though “Yeah, but do they exist?” So I started with one group of images I just read about, which is a series of Polaroids that the Stasi took and I asked them “Do these images still exist and may I have a look?” They said “Yes, of course”. I just had to make an appointment. Then I came across very absurd things and kept asking “Is there more like this? Is there more like that?” It took a while for me to realize what the book might look like in the end, with the three different chapters and three different directions, like teachings and how to become a spy, how to act like a spy, and how they interact with each other. So it took quite a while and I was very astonished by the normality of many of these images; that they’re so incredibly normal-looking documents.

“These images were never supposed to leave the agency ever. Never ever. So we were not supposed to look at these images ever…”

Given that there was so much material, what was your criteria for inclusion?

It’s very difficult to say. Some images I didn’t want to see. These were very terrible images like hidden cameras within private apartments of nude people; I didn’t want to look at politicians being shadowed, or so on, which is boring in a way because we all expect this to be there. I wanted more to have this internal view. That was more interesting to me; like the teachings where they’re taught how to disguise themselves. Images like this, where they just interact with their colleagues and these images were never supposed to leave the agency ever. Never ever. So we were not supposed to look at these images ever. For them it’s unfortunate, for us it’s a treasure trove to have this archive available as it is. Then I also wanted to look at some more classic images, like surveillance of a post box or when someone is followed by agents. But I was far more interested in this internal view of the Stasi and this world that surrounds them.

When we look at the photos today, with the disguises especially, there’s a bit of an absurdity and humor that comes along with them. Do you think this makes the content easier to normalize or even harder to grasp?

The thing is, I keep thinking about this absurdity in many of these images. Yes, you’re right, they look absurd. But I must say it also has to do with the fact that these images are 30-35 years old. Back then, if you look at your private photographs of your parents 35 years ago, they look different from nowadays. I think it’s because people used to act differently in front of the camera. They had a different approach to photography, which now looks absurd to us. The clothing is different, almost like hipsters. So I think much of the absurdity comes from this. But then we keep laughing about these images, they look funny, they do. They are very absurd. But these were techniques that were used within society. For instance in the Teaching chapter there are images where they staged a shadowing of someone, where they play the game of following and taking pictures. When you flip further through the book, you have the real ones. So you have to keep in mind that even though these things look absurd to us, it’s real; these were the teachings. And so I think you laugh, but the laughter sticks in your throat. Then it gets difficult to cope with it and I think that’s an important point: That you can laugh, but you have to realize “Why the hell did I just laugh because it’s a terrible image I’m looking at.”

“It would be so interesting to have this unique situation of having two different political systems within one country within the same time frame, looking from two opposing political sides on the same situation of the Cold War, but it’s not possible.”

What do you think this collection of images says about the state of surveillance today? Does it put current practices into perspective as part of a continuum?

That’s difficult, because back then, in the 80’s, the Stasi was on the same level as the CIA or KGB, in terms of what they could do within society. They were up to date back then, technically and everything. They had a high class surveillance operation that ceased to exist. If they would have continued, of course they would have had something like a prison program, definitely. They would have also tried to put their surveillance operations on top of the internet and everything. They ceased to exist. The thing is, in Germany we have this very special situation; we now have one country that used to be two countries with two sets of surveillance operations within the same country. Also, I wasn’t just interested in what the Stasi did. I also approached BND, Bundesnachrichtendienst, which is the surveillance service that’s still operational nowadays and they told me “Yes, of course these things do exist”. Similar images, they do exist, there’s just no political will to ever show them to the public. This is why it would be so interesting to have this unique situation of having two different political systems within one country within the same time frame, looking from two opposing political sides on the same situation of the Cold War, but it’s not possible. So the only things we can look at are the Stasi files and the most important images for me, for my understanding of the whole situation, is pretty much in the middle of the book where you find some images of agents from the Western secret services and they meet with the Stasi and both sides take pictures. That tells a lot about the same state of mind they’re in, even though they’re on opposing sides. I would guess they could have met for coffee or beer after work, because they did the same thing, just from another perspective. I think they would have found a basis for communication.

We can’t see them, but do you think those counter-part images would tell a different story?

No, I don’t think so. I think it’s like playing on an opposing team of soccer or football. They are on an opposing team, but after the game, they could meet. Well, unfortunately, I even tried to get access to some of these images, I know for instance some of the agents seen in these images are British agents. I know the file still exists. I also know in which archive they are stored, but there’s no way for me to get access. I would love to show both pictures, but it’s not possible.

Why do you think that is?

I have a quote from one of the people I spoke to at the BND. No names, but he told me if I look at these disguise images from the Stasi, I have to keep in mind that the person who’s shown in this image wasn’t the highest ranking officer back then, but now he might possibly be in charge of a whole department, or something. So in these Western spy agencies, these people still work for the organization or these are the ones who taught, the grandmasters, or the ones who brought in those who are now in the top ranks of the organization. So it’s a continuing operation and therefore, there’s no interest from their side to open up, because some blame might be brought.

“The terrible thing is that these surveillance operations, they use these images as proof, even though these documents, these emails, these phone calls, all too often they can prove what you want them to prove.”

So on the issue of perspective in surveillance, we tend to imbue these images with a false objectivity. Like you’ve said, it can be easy to forget that there’s a person using discretion behind the camera and the potential for misrepresentation. Do you think that power dynamic changes as practices become more digitized or computerized?

I fear that this is what they think happens. But in fact, from my understanding, when I look at images, I never find that images actually work as proof of anything. It’s always someone behind the image, looking at the image. And you find plenty of examples in the Stasi files, where you look at an image and you say “Wait, wait, does this image exist?” For example, the image of a coffee maker. You look at it and it turns out it’s a West German coffee maker. So still, if I look at the coffee maker, I think “Oh, someone loved coffee,” but I’m absolutely sure that when the Stasi officer looked at the coffee maker and realized it’s West German product, he thought “Oh, context to West Germany.” Both things are inside the same image, there’s no proof of anything. But the terrible thing is that these surveillance operations, they use these images as proof, even though these documents, these emails, these phone calls, all too often they can prove what you want them to prove. This never changes, I guess. And the problem with the Stasi and if you look at the history of the Stasi, which is an open book, fortunately, was that the Stasi kept growing over time. It peaked shortly before the downfall of the communist regime. They always believed in the fact that West Germany wanted to destroy the communist society and they couldn’t find proof of that, but from their perspective they knew that this must be the case. And since they couldn’t find the proof for this wide-spread conspiracy against the communist system, they thought the only logical explanation was that their surveillance operation was not big enough to find it. Therefore they kept growing. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, we came to realize that actually West Germany really didn’t care about East German politics that much. Most politicians in West Germany were absolutely happy with the East German system; it looked stable. Therefore they didn’t try to destroy the system, in fact they helped them with money through black channels. They bribed the East German politics because they were so afraid that the system might fail. They couldn’t find the conspiracy within their society, they would have never thought that there actually is no conspiracy. They couldn’t question. I think this is the same problem with any surveillance operation, because questioning this means questioning your whole operation. You’re there, so there must be a reason for your existence. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy and therefore there must be a threat.

“Almost no one realized that their apartment was searched at the time, which is terrible and you find thousands of these images.”

What did you find most interesting and what surprised you the most? Out of all these images, is there a particular one or a group that resonated with you?

One group I’d mentioned before was where these agents meet each other. The most hurtful and terrible images I found, were actually the ones I was first interested in, I had read about them. They were these Polaroid images. They show very normal East German apartments, but they were taken by the Stasi before they performed secret house searches. These Polaroid images only exist because when they broke into a private apartment, they didn’t want to leave any traces. Therefore first they took these Polaroid images of interesting looking aspects of the apartment, to be able to put everything back into its original place, after they searched through the house. Therefore these are so terrible images, because now you look at them and it’s just an unmade bed, but if you realize it’s just an unmade bed, but the picture’s only been taken because the bed is searched through afterwards. These are very very bad images and I kept thinking about including them into the book, because it’s such a bad thing and I’m in the danger of repeating these bad things. I had many discussions with the archive, but we all concluded that it’s far more important to show them as historical documents. The danger is relatively small that someone might realize whose apartment it is. So therefore we included them, but we didn’t include any background information on whose apartment it is. But they still shock me these images.

Especially because they look so harmless.

Yeah, they are in a way. Because someone just left their apartment. And most people learned about this, if they ever did, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Almost no one realized that their apartment was searched at the time, which is terrible and you find thousands of these images.

Are you working on any new projects?

It’s not at the point where I can talk about it. It’s difficult to work with archives from an artistic perspective. I have a project in mind, I’d love to work with a certain archive, not a German one. It turns out to be very difficult. Feeling-wise it’s much nicer to take your own pictures, because you take a picture and it’s yours and you can do whatever you want. With archived material it’s very tricky because so many people believe they have the right to say something about your use. So maybe another archive project sometime in the future, but more personal projects are more important to me now. But this book is pretty much what I was looking for three years ago. Definitely I’m quite happy that there’s a book now that people can look at. The thing is, I don’t want to spend my whole life with this archive. I could. There’s so much more to see; it’s an endless material. My participation in the whole debate surveillance and what surveillance is, and the limits of it is not going to end very soon. It’s just my share in this conversation and others are free to approach the archive and continue this work. I’m very happy about that. I’m going to buy their books as well.

For all the visuals © Simon Menner and BStU 2013