Dan Witz: Hidden in Plain Sight

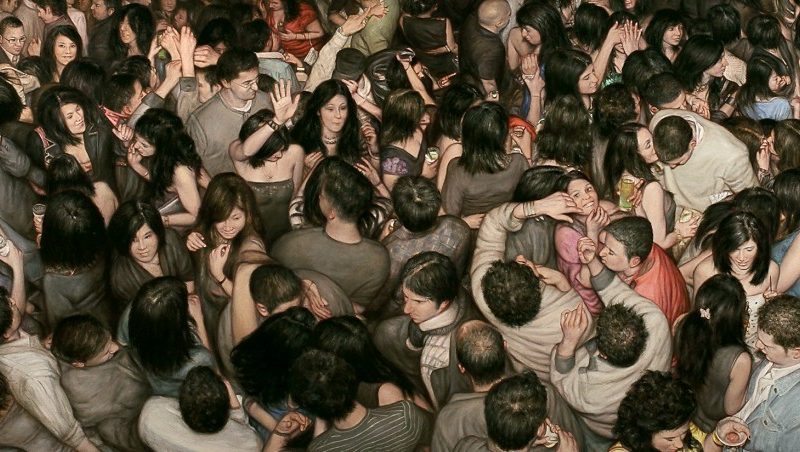

For years, Dan Witz’s striking yet intricate work has decorated both galleries and the streets. Focusing on realism while at art school, a practice then widely considered out of style, Witz embraced the punk ethos and has long been creating pieces that reclaim public spaces, catching viewers off guard. Leaving unassumıng humming birds on the New York streets in the 1970’s, working on campaigns with organizations such as Amnesty International and PETA, and, recently, lining gallery walls with dizzying paintings of hardcore mosh pits, Witz brings together two seemingly opposed realms of art. We were lucky enough to talk to him about his career, his passion for realism, the development of street art and his views on its role in creating social change.

Interview by Leyla Aksu

Can you tell us a bit about how you first got into art? What was art school like and what drew you to realism?

Growing up, if there was any one specific thing that I could point to that made me want to be an artist, it was R. Crumb and Underground comix. From these guys I picked up the notion that the best art was confrontational and countercultural, and that art was a higher calling – a way of life not a job. The big cliché at the time was that most artists were tragically misunderstood and starved and lived in garrets. This really appealed to me. But still, when I went east to art school there was some anxiety about how I would survive and support myself. This was in the late 1970’s though. New York City was bankrupt and in seemingly terminal free-fall. Rent was cheap downtown, privation was the norm, and part time jobs were enough to sustain a minimal lifestyle. In this world, punk rock, with it’s war cry of no future seemed like a reasonable life style choice.

At the time there wasn’t much realist painting around that I could relate to. Representational art was completely ignored by the mainstream magazines and was looked down upon by most of my fellow students. I understood that traditionally, most artists used their academic training as a jumping off point to more contemporary modes of expression (think Duchamp and Picasso), and that if I wanted a viable career as a New York artist I needed to follow that path. But I stubbornly stuck with the realism. I think that from the punk scene I saw that rebellion was sexy. And the budding contrarian in me sensed that a more accessible, more egalitarian type of art might be a good way to irritate and supplant the status quo Underground comics and could possibly turn out to be a worthwhile artistic identity (or career plan).

What is it about punk – the movement, style, and/or music that you mostly identify with? What got you interested when you were younger and what does punk mean to you now?

Long before I knew what punk rock was, I was drawn to artists and musicians who went their own way and didn’t care what others thought about them. So most of my childhood art heroes were sad self-destructive types, dark horses, drunks, addicts – most of them seemed to burn for a couple years of intense genius then flame out dramatically. My adolescent thinking went – the world’s a fucked up place (no future), suffering’s the only honest response to this condition, so the ‘authentic’ artist burns bright, then out. By definition, a long healthy life for an artist had to involve compromise and betrayal.

So you can see how primed I was to move to dirty dangerous New York City in 1978 when punk was peaking. Being right up close to the Clash, the Ramones, Devo, the kids breakdancing, the graffiti bombed trains, the punks on St. Marks – by comparison, art school seemed self indulgent and out of touch.

And most art in the galleries turned out to be a huge let down. My impression was of a gated community, an exclusive reserve for older white people designed primarily to keep the riff raff (like me) out. From what I saw around me, to make a career in that world, it didn’t seem to matter how good or original your work was, most importantly you needed to curry favor, be ‘taken up’, and meet and impress the right people. To me, this was what was wrong with art, and the world, and definitely not my idea of burning bright.

After a few beers and the right kind of music, it seemed like the whole business was so corrupt and decadent that it needed to be taken down. In response, I began doing street art – subverting that whole commodity/value paradigm, and me and my artist friends started bands. This, between minimum wage jobs, is what I did for the next seven or eight years.

You’ve mentioned that you see yourself as a welcomed outsider at hardcore shows. What was it that drew you to paint mosh pits and how do you capture and translate such intense movement?

A lot of my themes have come from those early experiences living in downtown NYC and playing in bands. The group figure paintings definitely come from that and a lifelong interest in baroque forms – how astonishing it is that a flat composition of shapes and colors can evoke such physicality and presence. Also, as a quasi-traditional painter, I feel compelled to pay tribute to my forebears, and their hierarchy of genres – still life, landscape, portrait, and, the highest, the penultimate, the multi-figure history pieces. I’ve worked my way through them all but find my greatest rewards in the mosh pit and rave compositions.

You use both oils and digital media in your paintings. What’s your creative process like? What do you look for while preparing your compositions?

I always work from my own photographs – and I take photography very seriously. For the concert pieces I put on steel-toed boots and try and get the camera as close as possible to the eye of the mosh pit. My street art usually originates from studio photos that I digitally manipulate in Photoshop. All my source images go through a fairly intensive digital re-think before becoming the actual references for my pieces. Over time I’ve gotten deeper into Photoshop and have come to regard it as important a tool for me as paint or brushes.

I really enjoy the photo prep part of my process. Especially the hunter-gatherer part. There’s nothing like plugging in after a hard photo shoot and seeing what has been caught by the camera. I also look forward to the ridiculously complex and overwhelming process of constructing the compositions. Puzzling these together can take months. After I have the digital file printed in monochrome on the canvas, then comes the long hard slog of the actual painting, a gestational feat which, to be honest, is ridiculously difficult but never becomes routine.

The role and use of light seems to be an important facet of all your paintings. How do you translate that to your figure paintings and portraiture?

In 2002, the summer after the 9/11 attacks, I did a street art series of trompe l’oeil candle shrines installed on the bases of light poles in Manhattan. From this experience I’d become interested in the different techniques, the tenebrist old masters used to paint light. It was amazing to me how they could not just simulate light in their paintings, but create canvases that actually seem to produce light. All my subsequent projects have explored and expanded on this.

The “Wailing Walls” campaign you did with Amnesty International in Frankfurt is very intense and highly influential. What does this project mean to you personally? How has it been different for you than the other street-art work you’ve done? Have you had chance to experience the reaction it got on the street?

Sometimes I like to stick around and see people’s reaction to my stuff. But these encounters usually come off as pretty random and don’t figure too seriously in my creative calculus. The majority of feedback I get is online, which, after wandering out there alone in the desert for so many years before the internet, I really appreciate. And yes, at the time, the 20 or so Wailing Wall pieces in Frankfurt were one of the peak experiences of my career. Oddly, while doing that project, even with all the media excitement (and the accompanying police attention), there was no pressure on me to compromise my normally aggressive installation techniques (these days, to avoid easy theft I anchor my grate pieces into the wall, which involves serious industrial adhesives and a heavy duty hammer drill). It turns out that Amnesty International, despite its mainstream profile, can be surprisingly bad-ass if it wants. They recognized that my methods, although illegal, were an effective way to galvanize a jaded public’s attention. If anything, they even pushed me to go larger and bolder than I usually do. I date a big growth in my street practice to that first Amnesty project.

I’ve also done a few collaborations with PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) in the last few years, which have been hugely gratifying.

As someone who’s been doing street art for so long, how do you feel perceptions and attitudes towards the practice have changed throughout your career? Have those changes affected you at all?

These days, to keep street art fresh, I find myself focusing mostly on these projects that address social issues, which matter to me personally. Back in the 1980’s, the mere idea of an art form that wasn’t for sale and couldn’t be owned was enough of a subversive sub-text to keep me going out and taking risks. But in the present culture, with so many people doing street art and sanctioned murals, just putting something on the street isn’t as transgressive as it used to be. Activism seems like a logical development for an art form that exists on the public commons.

We necessarily need to be disturbed by and reminded of things in order to try to prevent us from forgetting. Can you tell us about your views on how the production of culture and art has the power to impact social and political change?

I think that a lot of us like to hope we’re doing something along those lines. But it’s hard to tell. This is probably why I’m drawn to the activism. I just heard that the campaign I worked on last summer with PETA in Washington, DC has succeeded into shaming the NIH into cancelling their psychological terror experiments on newborn monkeys. Of course, the NIH denies outside pressure made them de-fund the program and I’m pretty sure my little street interventions weren’t that significant, but it still feels pretty good. As far as any larger cultural shift goes, I have to say that with the wildly subjective nature of today’s media, once solid concepts like truth or meaning have become so shifting and elusive that I’ve given up trying to pin anything down. The best I can do is keep my own inner workings as solid as possible and hope it radiates outwards.

What is your relationship with younger generation of artists like? Do you get along well?

Yes. They’re very respectful. Sometimes alarmingly so. The truth is that without a mirror, I tend to forget that I’m older (I still feel around 24), and that seems to nicely level the conversation.

Do you remember the first hummingbird you painted?

Absolutely. It was outside the Mudd Club, a music venue/nightclub I regularly patronized in the late 70’s and early 80’s. I’d used gouache, which is water soluble, thinking that it would be art-smart and super profound to paint something as transient as a hummingbird, in a transient medium that would dissolve slowly and poignantly over time. But after a couple of rainstorms and seeing how crappy they looked, I switched to the more weatherproof acrylics.

You’ve mentioned “invisibility” in regards to your work before – your street art hiding in plain sight, the anonymity of technique within academic realism… Is that important to you?

Yes, anonymity has become a (non) signature of mine. I do believe, though, that a certain remove is crucial to the impact of what I do. The street work from the last four or five years has been a variety of strategic approaches to slipping subversive imagery onto the public commons–to have it right out there in plain view, but still keep it subtle enough so it doesn’t flag the attention of the authorities or the street art vandalizer/collectors. Starting in 2010, I began installing my “Dark Doings” pieces on walls beside highway ramps and interchanges. I chose bottleneck locations where traffic would be backed up and there would be a captive audience passing by at low speeds. I called the series “WHAT THE %$#@?” (WTF) because this pretty much seems to be the universal reaction to the pieces. Often, on the tail of the “WTF” reaction, comes something like, “How long has that been there?” or “How many times have I passed that without seeing it?” The first time I heard that I was overjoyed. I mean, if my work had to have a take away, or a message, I couldn’t think of a better one than, “What else have I been missing?”

As far as my academic approach to technique, my primary pictorial goal has always been to create utterly believable light, space, and presence – especially presence – like those technically brilliant but largely forgotten academic artists did. One of the main things that attracts me about these guys is the pure functionality of their technique – how the artist’s brand and ego are sublimated, how the picture’s chief objective is not about who did it and how brilliant they are, but more about the narratives or visual fancies they’re concerned with.

I’ve always been obsessed by what those guys could do with oil paint. And how poignant their failures as artists were. In fact, I’d have to say that their ending up in the dustbin of history has had an almost motivational effect on me. I totally understand why their names have been forgotten – but, and this goes back to my early decision to stick with the realism – I’m still convinced that something as profound as this way of painting should have a voice in the larger cultural dialogue.

What are you currently working on? What has been inspiring you lately?

My studio is jamming right now, overflowing with new pieces. I’m in full production on a big street art intervention for London, re-purposing some iconic British phone boxes (watch for a Kickstarter to help get me over there). And in April (2016), I’m having a solo show, “Mosh Pits, Raves, and One Small Orgy. New Paintings by Dan Witz.” at Jonathan Levine Gallery in Chelsea, NYC.